Super glue and animal antibiotics are in the medicine cabinets of many farmers and ranchers in Texas — tools of the trade they sometimes use on themselves to avoid a trip to the doctor. It’s not that they have anything against physicians. It’s because they either lack health insurance or their coverage is so limited that a doctor visit could saddle them with a hefty bill.

I know this because I’ve seen the glue (used to seal wounds) and animal meds in first-aid kits of some of my family members who are uninsured farmers and ranchers in South Texas. And they’re not alone. Nationwide,10.7% of farm household members had no health insurance, higher than the 9.1% for the U.S. population, according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture report using 2015 data, the most recent available.

Finding adequate, affordable health insurance can be a huge challenge for people who run small, family farms or ranches, said Alana Knudson, director of the NORC Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis. That’s because many farmers and ranchers are self-employed, with no access to affordable group plans, and have low incomes. Even other private plans with limited coverage are often inadequate and pricey.

“It’s very cost-prohibitive for farmers and ranchers to be able to get and maintain health insurance,” Knudson said.

The problem is widespread but not often tracked closely by many states, including Texas. There are about 3.4 million farmers and ranchers in the country, according to the USDA’s 2022 Census of Agriculture. Because many are self-employed, they’re at a high risk of being uninsured or underinsured, endangering their health, Knudson said.

To gain health insurance, some farmers and ranchers take a second job off the land with an employer that offers group coverage. Or, their spouses work full time to get health insurance for the family, such as at a local school district or municipality.

Others in middle age, like my Uncle Todd, who lives near New Braunfels, Texas, decide they’ll wait until they’re 65 and can go on Medicare, even though it means risking physical injury from their work every day. Todd has about three years to go and lives alone in a cabin on my family’s property in Comal County, about 36 miles north of San Antonio.

Texas leads the nation in the number of farms and ranches, with 248,416, and has the highest rate of uninsured residents, at about 18%. The state has refused to expand Medicaid to cover more low-income adults, so it’s likely many farmers and ranchers have little or no health insurance. The rural areas they live in suffer from shortages of doctors and hospitals. From 2005 to 2023, a total of 24 hospitals closed or reduced services across Texas, according to the University of North Carolina’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research.

Even if Texas expanded Medicaid, barriers to health care would remain, said Dr. Rick W. Snyder, a Dallas-based cardiologist and president of the Texas Medical Association. Many doctors in the state won’t accept Medicaid patients because the reimbursements are so much lower and slower than private health insurance.

“Coverage is not the same thing as access, and access to waiting lists is not the same thing as access to health care,” Snyder said. “So just because you have a card that says you are covered by Medicaid does not mean you’re going to find a hospital or a physician who actually accepts that.”

Dr. Doug Curran, a physician in Athens, Texas, said the low reimbursement rates are stark compared with private plans.

“Medicaid will pay you about 28 bucks for seeing a kid with an earache,” he said. “You know, you can’t even pay the electric bill, hardly, for that.”

In 2021, the Texas legislature began allowing the Texas Farm Bureau, an agricultural nonprofit, to sell its members health plans that do not have to comply with the Affordable Care Act’s consumer protections, such as rules that prohibit insurers from discriminating against people with pre-existing conditions.

Texas Farm Bureau plans aren’t considered health insurance and operate without oversight by state insurance regulators. Monthly premiums are often lower, but the lack of ACA rules could mean higher costs for farmers and ranchers when they seek care.

Most people who sign up for these and other alternative plans tend to be self-employed, concluded a 2023 Government Accountability Office report.

Some farmers and ranchers I spoke with don’t bother with a doctor anymore, not even for medication. Instead, they use antibiotics made for livestock they buy from a veterinarian or feed store. This workaround became more difficult in June 2023, when the Food and Drug Administration tightened access to antibiotics in an effort to combat bacterial resistance; some of these drugs had long been available over the counter. A veterinarian’s prescription is now required.

Kenneth McAlister, a fourth-generation farmer in Electra, Texas, takes another tack. “I go to Mexico about twice a year and I’ll buy a lot of Mexican antibiotics.”

Before the ACA, McAlister said he and his family had private insurance through his wife’s job as a teacher’s aide. But after their children grew up and left home, it didn’t make financial sense for her to keep working.

Now, McAlister has coverage through a national insurer, but said the plan wouldn’t cover the full cost of the knee replacement he needs. So he’s waiting for five years until he can go on Medicare.

“I can’t afford to have my knee done. If I hit the lottery and win millions of dollars, I might consider going to get it done before then,” he said.

McAlister pays cash on the rare occasions he goes to the doctor — like on the Sunday he went to the emergency room to get a fish hook removed from his finger.

“I have no idea what the best thing to do is,” he said. “I’m hoping that I can find something along the way that maybe is better than what I got.”

Risks of a Rural Life

Farming and ranching have given my family financial independence – and caused some members to suffer injuries to body and spirit.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranks farming and ranching as some of the nation’s most dangerous occupations. Since I was a kid, my mom has told me stories about family friends who were injured or killed when their tractors overturned — a leading cause of injury or death for farmers.

Family members share that risk.

My 89-year-old Aunt Corinne told me recently that when she was a child, she was her dad’s – my great-grandfather’s – “right-hand man” on their 1,500-acre ranch in the Texas Hill Country. She helped him work the land, riding a horse named Booger Red.

The work and risks didn’t end when she got home. At age 6 or 7, she got her arm stuck in the washing machine. Back then, people put their clothes through an electric-powered wringer. She suffered nerve damage and still can’t feel part of that arm.

“Mama finally got it stopped when it got up out of here,” she said, pointing to the scars on her upper arm. She wasn’t rushed to the hospital. “You didn’t do that. You just took your meat and pushed it down.”

The increasing cost of health care has limited the ability of some U.S. farmers and ranchers to increase their operations because they’re unable to work the land full-time. They have to work outside jobs to get health insurance; when they come home, they must feed the animals, repair the fences, help a cow give birth and plow the fields.

“It’s a big responsibility, you know, it’s not an eight-to-five job. It’s round the clock,” said Robin, a family friend and farmer from the Hill Country. She asked that only her first name be used. “Farmers and ranchers just don’t have any idle time, really. There’s always something to do.”

Robin went to school with one of my aunts and attended the same Lutheran church as many of my relatives. Her small farm, like ours, has been in her family for more than a hundred years.

She and her husband both work outside the farm to help cover expenses and pay for health insurance. Her husband sometimes jokes that they should move into a condo. But they were both raised on a farm and that’s how they raised their children, who enjoyed wide-open spaces and learned how food is made.

“It’s bred in you,” Robin said. “It’s just something that gives me pleasure that I can keep dad’s livelihood going. The cost is big — a lot of times you don’t break even, but, you know, it is what it is.”

Sometimes families barter for health care using what they produce.

“You can trade out some stuff — doesn’t have to be exactly equal value — and you can just figure out what’s fair and give them some help,” said Dr. Robert L. Hogue, who lives in Brownwood.

Even when farmers and ranchers have health insurance, few are completely satisfied with the coverage — and it doesn’t fix the problems inherent in rural living.

The quality of rural care can be low. Derisive nicknames, like the Quack Shack and Death Valley, abound. There is limited or no coverage for mental health and substance use disorders, and sometimes there are no mental health care providers nearby. It can be a long drive to a doctor’s office or hospital. In my family’s case, and others’, the roads aren’t paved and are prone to flooding by creeks, which delays or blocks ambulances.

Aunt Carrie told me about the times she went into town with Hilda Mary Acker, her grandmother — my great-grandmother — and because it had rained so much, they couldn’t cross the creek. So they had to stay in the car until the water went down, sometimes all night.

The ambulance may not arrive.The majority of rural Texans live in so-called ambulance deserts, where they have to wait more than 25 minutes for an emergency medical team to arrive, according to a 2023 national study by the Maine Rural Health Research Center.

In many parts of Texas, the ambulance service is staffed, at least in part, by unpaid volunteers, Knudson said. So response times depend on the availability of those volunteers, and funding is limited.

“It is supported by bake sales, spaghetti suppers, pancake breakfasts, you name it,” she said.

Despite filling a critical need, EMS workers in Texas — and well over half the country — are not recognized by the state as an essential service. If they were, as is the case in 13 states and the District of Columbia, the state and local governments would have to fund and provide emergency medical services that meet a minimum standard of care.

A Quiet Distress

I’m a seventh-generation Texan and one of the few members of my family who isn’t a self-employed farmer or rancher. Instead, I’m a self-employed journalist who now lives in New York City. But that doesn’t mean my family’s land in the Hill Country isn’t part of who I am.

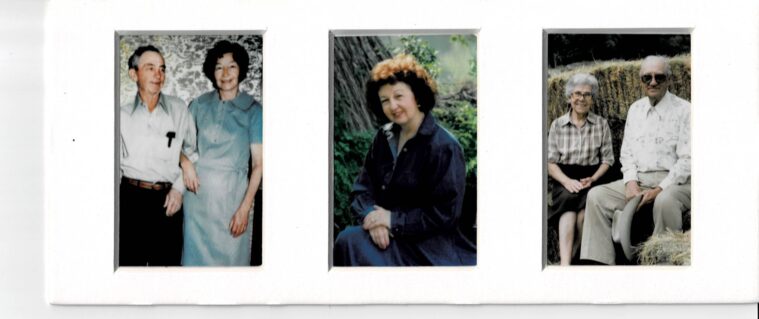

I often think about my ancestors who lived – and died – there. I have a framed photo collage of two generations of my farming and ranching family in my bedroom. I often think about how, even though I’m not in Texas, I still want my loved ones and the 261,666 other self-employed farmers and ranchers in the state to have a healthier life than their ancestors, with access to quality, affordable health care.

One of the women in that photo is Hilda. She was, and remains, the tallest woman in my family, at 5’7”. Even though I’m 5’3”, I’ve been compared to her for most of my life. I, too, have scrawny arms, enjoy writing and smoke cigarettes. But Hilda, who was known as Omie, was a farmer who may have had lung cancer (relatives said she coughed up blood) and died by suicide only a few feet away from my childhood swingset. She was 60.

The story goes that instead of seeing a doctor, Hilda went to a psychic in New Braunfels who told her she was sick. In 1975, not wanting to burden the family, Hilda placed a shotgun between a y-shaped branch of a tree and pulled the trigger. Her son found her body.

The rate of suicide for farmers nationwide is 3.5 times higher than the general population, according to a 2021 report by the National Rural Health Association. After Hilda died, suicide rates eased nationally but began a relentless rise after 2000, particularly among male farmers and ranchers. By 2017 they were taking their lives at 43.2 per 100,000 population versus an average 27.4 for other workers.

Farmers and ranchers are reluctant to talk about their problems, and even when they do, care is often out of reach because they can’t afford health insurance.

To help close the gaps in access to care, the Texas Department of Agriculture implemented AgriStress, a toll-free helpline in February 2021.

My great-grandmother never let on that she was depressed. She wrote her feelings down in diaries. Maybe she had a pre-existing condition, or experienced stress over the future of the ranch. Or, maybe it was something else entirely.

“For the people who have been doing this for generations, and they are carrying out their great-grandfather’s legacy, now all the responsibility of that legacy falls on their shoulders. That’s hard,” said Amanda Wickman, program director of the Southwest Center for Agricultural Health, Injury Prevention and Education based at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler.

I’m trying to imagine any of my family members, insured or not, who’d even consider going to talk to a shrink. They’d probably be too embarrassed, thinking somebody would see their truck parked out front.

Maybe if they called that helpline from their tractor and could vent to a stranger they’d feel better.

I started this article thinking of my great-grandmother, wondering if she’d still be alive today if she’d had health insurance. What I’ve found is that the demands on farmers and ranchers remain complex.

Rural life has been mythologized, and, as with any myth, there’s truth at its heart. The nation’s food system depends on farmers and ranchers. But the health care system doesn’t benefit them enough. The difficult work of farming and ranching often brings isolation, tensions with urban America, culture and political wars, blame for rising food prices, and gaps in the health care safety net that shorten lives.

A lack of health insurance for the self-employed drove me out of Texas. Perhaps it drove my great-grandmother to an early grave. And it may be the reason my family eventually sells the land. But there’s still a chance that won’t happen. Maybe, in the future, health insurance will be widely accessible and there will be one less problem farmers and ranchers have to worry about.

This story was produced with support from the Center for Rural Strategies and Grist.