When Romain Dumas whistled to the top of the fabled 12.42-mile Pikes Peak hillclimb in a time of 8m53.553s, there were mixed emotions in the Ford camp. His Ford F-150 Lightning SuperTruck had set the fastest time of the event on one hand, but on the other, the Frenchman’s time could have been even quicker.

An unprecedented, brief, glitch with a sensor in the battery management system – while Dumas was passing through a dead zone on the mountain that inhibited the transmission of its on-board live telemetry – forced him to a halt and is estimated to have cost 26s before he got going again. That explains a 5.871s deficit to the time Dumas set in the outlandish SuperVan 4.2 in 2023.

But in every other respect, as F1 & High-Performance EV Manager at Ford Performance Sriram Pakkam puts it, “from a headline standpoint and from a learning standpoint”, the objectives were met.

“When everything else worked well, that's basically a testimony to how good our development tools were,” he tells Autosport in the days after the event. “This came in pretty consistent to what we were seeing from our simulators and from all of our computational methods. All of that stuff was really validated and nothing unexpected happened on any of those fronts. It came in very close to what we thought it should have been originally, so we're pretty pleased with that.”

The electric demonstrators make up one strand of Ford’s four-pronged motorsport strategy alongside its 2026 Formula 1 powertrain effort in collaboration with Red Bull, off-road disciplines including the World Rally Championship and from 2025 the Dakar Rally, and its programmes with Mustangs in GT3, GT4, Australian Supercars and NASCAR. The purpose of the EV demonstrators, Pakkam explains, is to push the boundaries of technology outside of existing series that have prescriptive rule sets.

“This kind of electrification arena that's come over the last decade, it’s still fairly new and you need a place where you can push this to the limits of physics and not an arbitrary rule set,” he says. “From that standpoint, it’s an awesome place to play in because you've got essentially no artificial ruleset that you're designing to.

“For engineers, that's the best place to learn, because you’re just going 'OK, here's your limits, it's the same ones you’ve seen in a textbook’. It's just the physics – ‘go keep pushing and get us the best result'. And there’s a freedom to that which you won't easily find in other places. The Motorsports Group is always designing to rules and so it's for all of the engineers on this, it's been a great template for playing around and doing things they’d never do.”

Pakkam reckons a team of 26 people worked on design of the Lightning SuperTruck, which has been in development since last autumn in what was a short gestation period.

Weight

Keeping the weight down was not only a significant challenge, but also an important consideration that has informed design decisions. The weight implications of chasing performance has been a “constant trade-off that you have to keep working on” for Pakkam and his team.

“It's fairly easy to get more aero and power because it's an attribute that is controlled by a couple of experts,” he explains. “Weight is trickier, because that's the distributed attribute that literally everyone is responsible for. It's about grinding away with everybody. Do you design your brackets better, more efficiently?”

“If we put in fourth motor into the Pikes Peak set-up, you'd be at a little more than 2,000 bhp, but that's a whole lot of horsepower more than your simulations you need”

Sri Pakkam

To Pakkam, the weight factor at Pikes Peak is “the most sensitive parameter you can do and make a change on to get lap time”. Unlike hiking power, downforce and energy density, he says the benefits of reducing weight “never tails off”.

“For us, weight was a key thing to go after because we maxed out what we knew Pikes Peak was responding to [on power], so we hit that limit,” Pakkam reveals. “Aero too, that started to kind of flat line out.

“We managed to get around 100kg out [compared to SuperVan 4.2]. On a big vehicle, it's still a smaller percentage of what we would have liked.” Although not as heavy as a road-going truck “compared to any race car this is pretty heavy”, he adds.

Powertrain

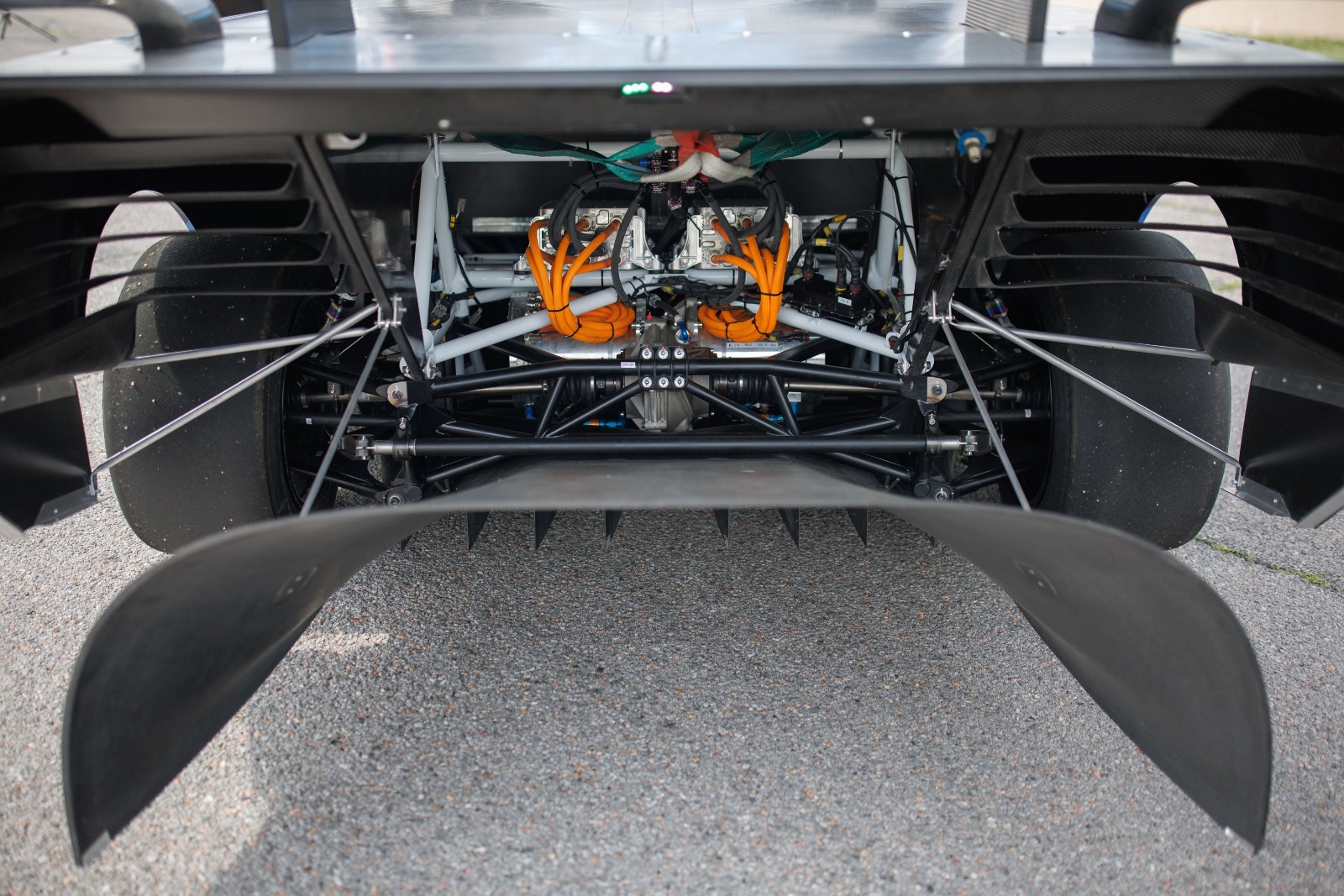

As it had done for SuperVan 4.2, which set the fastest time during the Goodwood Festival of Speed hillclimb last week, Ford went knocking on STARD’s door when devising the powertrain for its Lightning SuperTruck. The Austrian company headed up by former World Rally Championship driver Manfred Stohl contributed three UHP 6-Phase Motors and Ultra-High Performance Li-Polymer NMC cells (or a battery in layperson speak). These contribute to an impressive headline power figure of 1600bhp.

“We needed like a drivetrain that is basically race-ready, that is proven on the track, and so STARD was playing in that space,” Pakkam says. “We looked around for partners, and they were a great fit. They're engineering-driven. The base of it was solid. You have well-cooled batteries, well-cooled motors, a pretty power-dense package. That's what we needed at the time and we kept improving it since then.”

One motor is mounted at the front, the other two at the rear. Power distribution and torque balance is easily adjustable using rotaries on the steering wheel, allowing the driver to dial out balance issues without first having to stop and embark on damper or aero changes.

Pakkam says there is scope to add a fourth motor, as SuperVan 4.2 had when breaking the Bathurst electric lap record earlier this year, but it was decided this was unnecessary for Pikes Peak with the extra weight and battery drain this would entail - potentially resulting in less punch out of slow corners for a potentially higher top speed it would rarely reach.

“If we put in fourth motor into the Pikes Peak set-up, you'd be at a little more than 2,000 bhp, but that's a whole lot of horsepower more than your simulations you need,” says Pakkam. “Plus, you're adding weight and you’re drawing on more energy.”

Aero and styling

Ford “pushed the boundary so much over SuperVan 4.2”, says Pakkam, who points to an almost 30% increase in downforce on the Lightning SuperTruck. Its intricate triple-element front wing, enormous rear wing, detail work on headlight ducts and cooling louvres are the result of copious hours – “in the hundreds for sure”, remarks Pakkam - of CFD that Ford claims adds up to producing 6,000lb of downforce at 150 mph.

“It was from October to March basically running CFD on all our choices, constantly,” he says.

Lessons learned from developing the SuperVan played into this, particularly into packaging decisions for the battery and motors that resulted in “a better aero floor and a much bigger diffuser in there”. Aero sensitivity was “what we're mostly looking at”, alongside considerations of drag, he adds.

Pakkam says temptations to share parts across programmes for cost reasons have been eschewed, describing the SuperTruck as “pretty bespoke at the moment” largely because “the design case is so different.”

A desire to “keep development time as long as possible” and push back the start of testing was in part dictated by a lack of venues that offer comparable testing conditions to Pikes Peak. Once the physical vehicle had begun testing at “approximate facilities as close as you could”, which involved visiting proving grounds in Austria and Hungary that was “absolutely not representative in the way we'd like it to be”, any changes were made were not extensive.

“Set-up obviously changes, we had to kind of get into some minor aero tuning and add a few little bits there, but we’re playing in the margins,” says Pakkam. “After we hit the track, it's changing tyre compounds, anti-roll bars, little bits of aero, not anything huge.”

Chassis

Rather than being based on a production F-150 chassis, the Lightning SuperTruck is like SuperVan 4.2 of tube-frame construction. The need to fit a strong safety cage was an important consideration in that decision.

Bespoke tyres from Pirelli were developed for the Pikes Peak run, as Pakkam says “they're not used to this combination of power weight and aero”

“We’ve done our demonstrators in my group that are a production vehicle with hot racing bits put on,” he says. “The [F-150] Lightning Switchgear is like that, where we have essentially a production truck but with parts from our off-road racing programme and you can go do some high-speed desert racing.

“But you’re studying a different thing there; you’re stressing your production parts and drivelines and studying what happens to them. With this, we’re trying different things, focusing a lot on aero and how you maximise your energy usage and those sorts of things.”

Tyres and brakes

Bespoke tyres from Pirelli were developed for the Pikes Peak run, as Pakkam says “it's stretching a race vehicle in a way they don't normally see, they're not used to this combination of power weight and aero”. A starting point of GT3 rubber used by the new Mustang in GT World Challenge Europe needed finetuning to accept significantly more aerodynamic performance and mass.

“For everybody involved, it’s fairly unique,” he says. “It's a constant game of monitoring it, Pirelli helping us with recommendations on everything from warm-up procedures to what compounds would be best for that day based on what they know about it. So it’s constantly working with them to resolve, ‘what should we be putting on these things?’ Because we don’t know nearly enough at the moment how all these things react to such a unique vehicle and they’re helping us understand that.”

Stopping is achieved by carbon ceramic brakes from Alcon.