EVEN in death, Port Stephens pioneer William Cromarty continues to fascinate.

Think of the legacy the former master mariner left in the district. Besides being widely credited as the region's first white settler, the name Soldiers Point reminds us of where his early farm began almost 200 years ago next month.

Think now of other contemporary landmarks such Cromarty's Bay, Cromarty Bay Road, Cromarty Lane, Cromarty Creek (travelling by road to Stroud), Fame Cove, Fame Point, Mrs Cromarty's grave and links with the 'other' Carrington (near Tahlee), Booral and One Mile Beach. And surely Mary (at Soldiers Point) and Magnus streets (in Nelson Bay) are named after two of Cromarty's children.

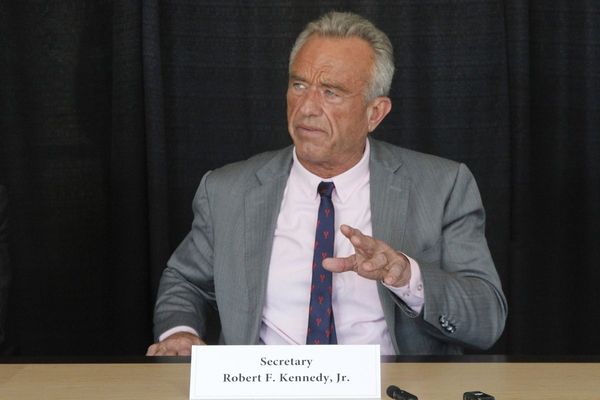

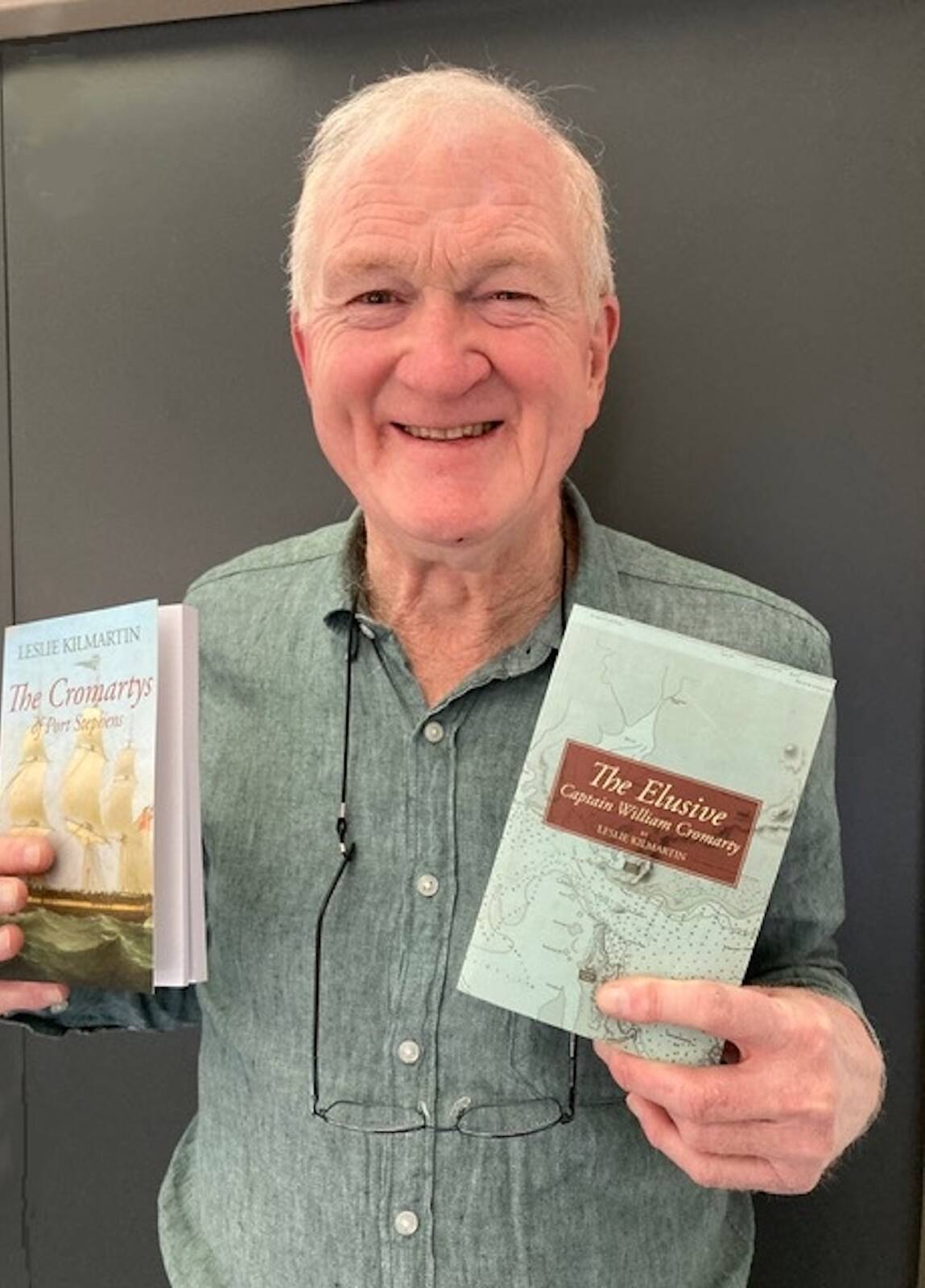

But William Cromarty (1788-1838) remains an elusive character for biographers. Just ask writer Dr Leslie Kilmartin, of Victoria, who spoke in the area last week after writing two books on his famous ancestor. William Cromarty is his three-times-great grandfather, but Kilmartin is still on a fact-finding mission to discover more of his ancestor's truly hidden history. He's recently published a slim (126-page), but valuable, book called The Elusive Captain William Cromarty after an earlier related work of fiction.

Why, there might even be a 'mystery' over seaman Cromarty's tragic end - off One Mile Beach - just short of his 50th birthday, although Kilmartin to date has found no evidence he was murdered.

"From my research, I think he was a great man. He deserves acknowledgement for his achievements," Kilmartin says.

"He's been described in colonial documents as a man of courage and as an excellent, active and intelligent seaman. Others saw him as very industrious and as a man whose skills were in demand."

Kilmartin said that besides being a person with inside knowledge of Newcastle and Port Stephens waters, Cromarty was an explorer, charting rivers. He was also in charge of cedar-cutting gangs near Karuah and, for about 14 months from 1834, was relied upon as the pilot guiding ships into a dangerous Newcastle Harbour. This ended dramatically when he was injured at work.

"In my book I've dispelled myths, but there's still gaps in William Cromarty's life I'd like to know about," the former pro vice-chancellor at Latrobe University said at a recent talk at Salamander Bay, where the audience included 20 other Cromarty descendants.

At the talk, organised by the Tomaree Museum Association and the U3A, Kilmartin also explored why Cromarty was granted 300 acres of land at Port Stephens, transferring this later, in 1827, to Soldiers Point. This was after losing his original land on the northern shore of Port Stephens granted only three years earlier.

Cromarty was forced to surrender his land on the Karuah River. That's because the new, government-backed Australian Agricultural Company (or A.A.Co) wanted it as part of their one-million acre land deal to grow fine wool there. Cromarty then worked closely with the A.A.Co from 1830 in various capacities, calling on his rare skills in navigation, sailing, exploration, road building and supervising convicts.

Meanwhile, his own farm at Soldiers Point seems to have not prospered as well as he wished.

Sir Edward Parry, the famous Arctic explorer and commissioner of the A.A. Co between 1830-1834 thought so highly of the port pioneer that he described him as a "rara avis" (or rare bird) in the colony, or in other words, an honest man.

Kilmartin believes the land transfer was allowed (two other similar ones weren't) with the A.A.Co even helping construct his Soldiers Point house as part of a 'sweetener' for leaving his original Karuah land grant.

But what were the "efficient services rendered to the (colonial) government" Cromarty was being rewarded for?

Kilmartin speculates Cromarty was perhaps doing significant government work without charge. A Cromarty business associate, Francis Shortt, once wrote that Cromarty and his work gangs (possibly pre-1824) saved many runaways escaping from the new northern penal settlement at Port Macquarie. Cromarty's success in securing 197 runaways contrasts sharply with the military's capture of only three.

These were savage times, according as a lurid 1825 account by Shortt.

In one case, nine convict deserting from Port Macquarie but only one man "nearly scalped by the ferocious cannibals" survived the bush. Six more were "butchered", while two drowned crossing rivers.

Later, in 1939, Cromarty's great-grandson, Howard Cromarty, told a Dungog newspaper the Karuah River Aborigines (presumably provoked much earlier) were hostile and would throw spears at their moored vessel, or brig. This further 'unknown' port history continues with the statement "Captain Cromarty fitted an iron cannon to the brig and this was loaded with grapeshot. During one desperate affray, it was fired point blank."

An exaggeration? Kilmartin also revealed an intriguing second cannon tale in a separate Cromarty family history. This was of Cromarty having a "cannon filled with sand to scare off inquisitive individuals while undertaking the sounding of the Hunter River". This cannon is said to be the same one held in a Port Stephens museum at Nelson Bay, but Kilmartin is not so sure.

Let's rewind the saga to its beginning. Port pioneer Cromarty was born in the Orkney isles north of the Scottish mainland. He may have found employment at age 12 in fishing fleets sent to Greenland and Iceland harvesting whales. Kilmartin said that, what we do know, is these "Orcadians" were remarkably bold and hardy mariners, best described as "farmers with boats".

Unusual, perhaps, for that period was that William Cromarty could read and write. He married a woman Cecilia (known as Sissy) who would later become a legend in her own right at her new home at Soldiers Point on the far side of the world.

William had arrived in Sydney by the ship Fame in 1822, seeking a new life for himself away from the impoverished rural scene back home. Sissy and children finally joined him in 1824 in Australia. But they were left alone for long periods as William probably sailed on the Fame in the coastal trade until 1825, even becoming its master, probably delivering supplies to cedar cutters at Port Stephens.

Their new family home at Soldiers Point, from 1827, was called Ronaldsha, no doubt a nod to Cromarty's Orkney home at South Ronaldsay. It was surprisingly away from the tip of the point, however, on high flat ground at Mary's Bay on the peninsula's western side, according to an 1866 map. Soldiers Point it seems was also originally known as 'Point Laura' (possibly named after Shortt's wife). The name change came after soldiers were based there to deter escaping convicts.

But it was a harsh bush life for the growing family, especially after William unexpectedly died with two others in the surf at One Mile Beach while trying to recover a rowboat.

There's far more though to the Cromarty saga, including why the pioneer graves of Mr and Mrs Cromarty are so widely separated. But that's a tale for another day - soon.