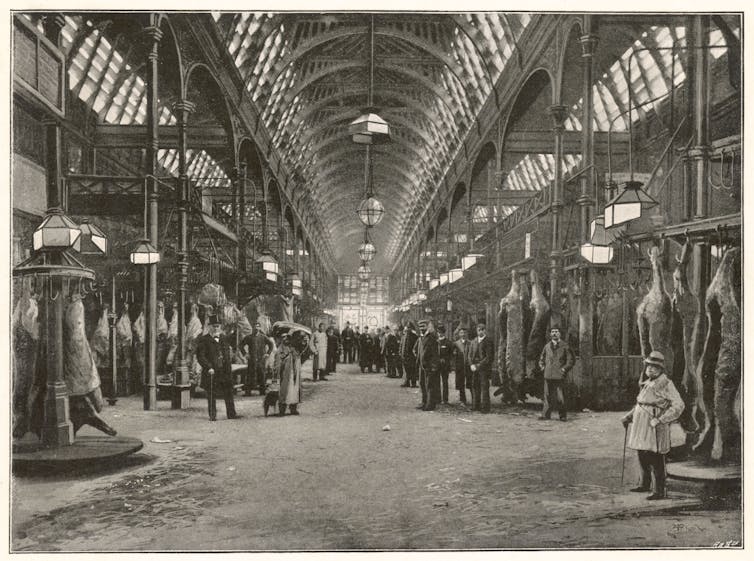

In the second half of 2022, the Museum of London threw a five-month-long leaving do in anticipation of departing from its home of nearly 50 years. The museum has been housed in London Wall, on the Barbican estate in central London, since 1976. It is now preparing to relocate to the Victorian buildings that, until recently, hosted Smithfield market, the city’s largest wholesale meat market.

This conversion of West Smithfield into an important cultural destination is part of the wider Culture Mile regeneration project. Moving a major cultural centre to an area in need of revitalisation, in this way, is of course exciting news. But for 800 years, this area has accommodated meat production including, at various times, livestock, cold storage, meat markets and an abattoir.

Since the 2000s, culture and creativity have been posited as a kind of magic formula by which to sanitise buildings that come with what we have termed “uncomfortable heritage”. When buildings with histories that some might find difficult – decommissioned prisons, psychiatric asylums, war-time structures – are put to other uses, the process often involves navigating between selectively remembering their history and omitting it altogether.

This also applies to abattoirs and meat markets because they are being converted against a backdrop of debates on the ethics of eating meat and the gory and sometimes cruel practices associated with its production, particularly as vegetarianism and veganism grows in popularity.

Urban meat production

Since the dawn of the modern era, many societies have pushed the sources of their meat further from the people that consume it. From the early 19th-century meat markets, private slaughterhouses and the like were primarily situated on the city outskirts to reduce the transport of living animals into the already overcrowded city.

At the turn of the 20th century, amid concerns about hygiene and animal cruelty, many local authorities set up public slaughterhouses to regulate the meat industry. Although they varied widely in size – from a single building to a vast precinct – these were, again, situated on the periphery of urban areas, capitalising on the railway network for livestock transport and ease of access.

These modern slaughterhouses were equipped with machinery to mechanise the slaughter process and speed up production. They were designed to function as machines for processing a large number of animals quickly.

With the growth of the agro-industry from the 1960s, meat production largely ceased in urban centres. While many of these historic slaughterhouses were demolished, some people have sought for those that survived to acquire cultural heritage status – in France, in Spain, in the UK and beyond.

Smithfield market comprises three grade-two listed buildings. Like many former city markets, these are large, architecturally interesting spaces in attractively central locations. Since the early 2000s, cities from Madrid to Shanghai have focused on how to reuse such buildings.

In 2006, the former municipal slaughterhouse and cattle market of Madrid, in Spain, was reopened as a contemporary art centre, the Matadero Madrid. In Copenhagen, with meat-industry related activities in the Kødbyen district shrinking, the council has similarly brought in creative industries. And in Portugal, the city of Porto is converting the 1910 Matadouro de Campanhã into an area for offices, art galleries, museums and auditoriums.

Common to these conversions is how they fail to tell the buildings’ stories. Avoiding mention of blood and guts is understandable, but that is nonetheless what these premises hosted.

Selective remembrance

The Shanghai Municipal Abattoir, now known as 1933 Shanghai, is a modernist concrete structure. The British built it in the 1930s to meet the demands of foreign settlers for beef and mutton. In 2006, like Matadero Madrid and Kødbyen, it was turned into a flagship project for the creative industries, featuring expensive shops and branding campaign events.

Paint, tiling, fixtures and fittings have all been stripped away. The former slaughterhouse has thus been transformed into a bare concrete sculpture.

This kind of transformation treats the human perspective as the most important aspect of architectural development and cosmopolitan culture.

1933 Shanghai’s spaces, which were designed to house animals awaiting death, have been reimagined as stages for cultural events, fashion shows and wedding parties. In the chilling hall, the gruesome sight of animal carcasses hung from ceiling-mounted conveyor belts has been replaced by lavish crystal chandeliers. The slaughter hall, where millions of animals were stunned, killed, bled and skinned, now hosts role-playing games and luxury car showcases.

Architects talk about “adaptive reuse”, to refer to how buildings can be reused. But such transformation is not just about recycling physical structures. It requires careful deliberation and conscious decision-making.

Every decision on how to retain or change existing structures and what kind of new uses to introduce to them dictates how we remember their past – or whether we remember it all. In the wider approach to reusing historic buildings, there are notable examples of design interventions that succeed in effectively evoking collective memories of the site’s history.

In the 2009 book Building Tate Modern, architecture writer Rowan Moore shows how Swiss architectural firm Herzog and De Meuron converted London’s disused Bankside Power Station into the Tate Modern, thereby retelling the city’s industrial past. A 20th-century industrial landmark was transformed into a 21st-century cultural icon, the former turbine hall and oil tanks reused as unique installation and performance spaces that capitalise on the outsized dimensions.

In Hamburg, Herzog and De Meuron similarly converted the 1960s Kaispeicher warehouse on the banks of the Elbe, into the Elbphilharmonie concert hall. By placing a new glass structure atop the mid-century brick, they emphasised the historical significance of the original structure and its bell tower, that dominated the soundscape of the harbour.

And in South Africa, British architect Thomas Heatherwick transformed a 1920s grain silo complex in Cape Town into the Zeitz MOCAA, a museum dedicated to contemporary art from across the African continent. Heatherwick retained much of the original concrete shell, ensuring it would continue to dominate the skyline on the Victoria and Alfred waterfront after a century. Inside, an ovoid atrium was carved out, recalling the organic structure and shape of a grain.

Reworking historical buildings inevitably engages with and alters our understanding of the past. But it can also engage with our present by making visitors consider the issues the building represents. Most meat-industry heritage sites, however, are converted in such a way that their history is all but obscured.

There are tools that could help here. Augmented reality technology could superpose images on to the physical environment of a slaughterhouse, to relay to visitors what workers and animals experienced in the building’s former life. Apps and audioguides could similarly give people the choice to engage – or not – with the history of where they stand.

Simply sanitising a former slaughterhouse, with culture and creativity, is a missed opportunity to engage more deeply with where our meat comes from. We should find ways to retell all aspects of these buildings’ stories.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.png?w=600)