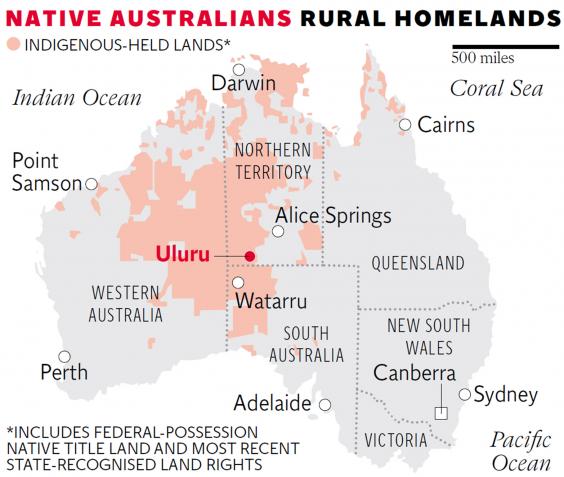

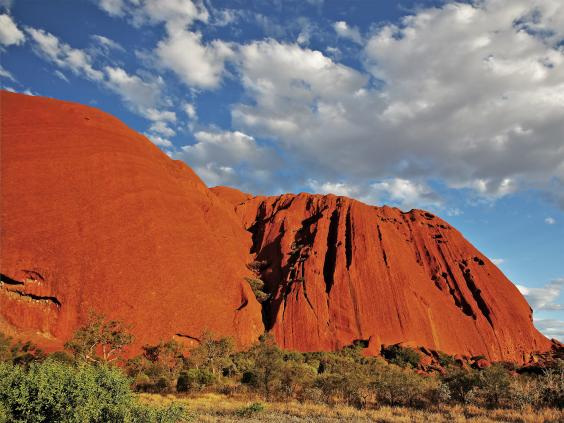

Thirty years ago this week, the Australian government returned Ayers Rock – the ochre monolith in the continent’s centre, now called Uluru – to its traditional owners. The high point of the Aboriginal land rights struggle, the “handback” was expected to bring jobs and tourism income for local indigenous people.

But at the anniversary celebrations, which featured traditional dances recreating ancestral stories as well as speeches from visiting dignitaries, community leaders – and even mainstream politicians – acknowledged that those dreams have largely evaporated.

Until recently, the Ayers Rock Resort – located in the sunbaked township of Yulara, about 12 miles north of Uluru – was almost exclusively staffed by white employees.

At the national park containing the rock, as well as another striking geological feature, Kata Tjuta (formerly called the Olgas), Aboriginal elders – who were supposed to play a key management role – have been sidelined.

And at Mutitjulu, a community in the shadow of Uluru, more than half of people are on welfare and most live in sub-standard housing. “We should be the richest place in Australia, with this tourism icon on our doorstep,” said Vincent Forrester, a former Mutitjulu community leader. He added: “Look around you – what’s to celebrate?”

The mood was very different in 1985, when the local Aboriginal people, known as the Anangu, saw their long battle to regain ownership of Uluru come to fruition.

At a ceremony in Mutitjulu, “everyone was dancing and singing… We were so happy that we got our land back,” recalled one traditional owner, Rene Kulitja.

Another local, Leroy Lester, said: “People thought, ‘My grandson will have a job and a house and a car. There’ll be food in the fridge and a green lawn to water. Even the dogs will be healthy.’”

The focus of many hopes was the park itself. After receiving the title deeds, traditional owners leased the land back to the federal government for 99 years. The plan was for it to be run jointly by the federal parks service and Anangu elders, combining millennia-old land management techniques and modern practices.

In the early years, joint management operated well. Elders such as Andrew Taylor, who was employed as a ranger for two decades, worked alongside white colleagues, teaching them traditional skills such as tracking, surveying flora and fauna, and “patch-burning” the landscape to encourage fresh vegetation.

In 2008, though, Mr Taylor and other long-standing Aboriginal rangers were laid off. They were told that their literacy and numeracy did not meet civil service standards. Now the park employs just two people from Mutitjulu, out of 38 full-time staff.

That means Anangu people are not performing work that is part of their culture, including looking after water holes, sacred sites and important animals and plants. Moreover, they have few opportunities to pass on traditional knowledge to young people.

Until 2011, the hotels and restaurants at the Ayers Rock Resort had just two Aboriginal employees. Now, following the resort’s takeover by a government agency and the creation of a new jobs strategy, which has included setting up an indigenous training academy at Yulara, more than one-third of staff are Aboriginal.

Again, though, locals have yet to benefit. Most trainees and employees are from other parts of Australia. For Mutitjulu residents, one major obstacle is low educational standards. As for tourism in the park, just one small, struggling Aboriginal-owned company operates there.

At the anniversary celebrations, even the federal Aboriginal Affairs Minister, Nigel Scullion, frankly admitted that little had changed in 30 years. “By and large, the rock looks the same, and, tragically, so does Mutitjulu,” he said.

Noting that hoped-for opportunities had not materialised, Mr Scullion added: “We need to make that change, and we need to make that now.”