EASTERN UKRAINE — As soon as the battered bus groaned to a halt outside the military hospital in eastern Ukraine's Donbas region, its doors opened and wounded Ukrainian soldiers began slowly hobbling off.

These were the walking wounded — more than 40 of them in all — with bloodied bandages and exhausted faces. Nurses rushed out with wheelchairs. One soldier struggling to walk limped over to a tree and threw up.

This was a rare first-hand view into the daily toll of the fierce fighting now raging in eastern Ukraine as Russia pushes its offensive here. And while many Ukrainians are still basking in the successful defense of Kyiv, the battle in the Donbas is a punishing grind that poses different challenges.

Here in the vast rolling farmland of the east, Russia's superior firepower gives its military a distinct edge, and its forces are inching forward day by day.

This week, Russian troops appeared to seize control of much of the town of Lyman, which lies at a strategic transport point. This comes as Russia pushes to encircle the nearby city of Severodonetsk — the last major Ukrainian outpost in the Luhansk region.

A senior American defense official says Russia has made "incremental gains," although its forces are facing "not insignificant" losses.

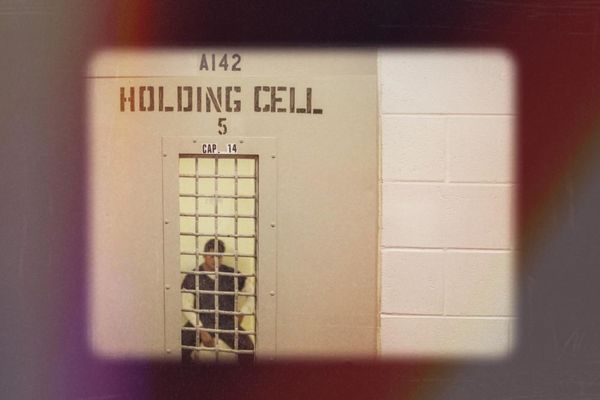

Ukraine, too, is taking a lot of casualties, which was clear during a recent visit by NPR to a military hospital near the front. Doctors and nurses moved quickly through dark hallways. Wounded soldiers, many of them asleep, filled beds in crowded rooms.

The facility is a primary treatment center for soldiers wounded on the northern Donbas front. NPR agreed not to disclose its location because Russia has bombed hospitals already in the war.

"We operate on around 100 patients a day here," said a senior surgeon, who spoke on condition of anonymity. "Three quarters of those are soldiers, the rest are civilians."

The surgeon's graying hair was trimmed short. He had bags under his eyes. After finishing a cigarette, he would quickly light another.

He has enough staff, he said, but the pace of work is grueling.

"That's why I look tired," he said. "We've been at war for three months, but I'm ready to be tired for as long as necessary in order for us to win."

Ukrainian soldiers say they don't have the right weapons

The Donbas is an agricultural and industrial region. Sprawling fields of yellow flowers and green sprouts stretch across the landscape. Giant slag heaps from coal mines dot the horizon.

This area has been at war since Russian-backed separatists declared breakaway republics in 2014. But the fight took on new urgency since Russia's full-scale invasion in late February, and Moscow's military is slowly gaining ground here.

The further east one drives toward the front lines, the fewer civilians there are in villages and towns. Most shops are closed. Traffic on the roads becomes almost exclusively Ukrainian military.

On a recent drive to the town of Bakhmut, around 30 tanks and armored personnel carriers could be seen — all moving toward the front. Damaged military vehicles loaded onto heavy trucks were heading in the opposite direction.

The geography of the Donbas makes this an artillery war, and Ukrainian soldiers say right now they are badly outgunned.

"As of today, Moscow has way more heavy weapons, including artillery and ammunition, and they're using it," said Sergej Shakun, a territorial defense leader in the Luhansk region. "We need more heavy weapons of our own."

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has been pleading for more heavy weapons for months. The U.S. and European countries have sent some but the amounts so far have been limited.

The Biden administration, for example, has provided Ukraine with around 100 howitzers, which have a greater range than Ukraine's own artillery.

Shakun said the American guns are helping, but he said they need more of them.

"The Russians are hunting those down," he said. "As soon as the howitzers fire, they have to relocate so they don't get hit themselves. As of today, five of the howitzers have already been damaged."

Ukraine's military is facing other issues as well.

On a recent morning in Bakhmut, a group of young soldiers expressed deep frustration with the military. They agreed to speak on condition of anonymity in order to speak candidly about the war effort.

They said they had only two weeks of training before being sent to Donbas to fight. Their weapons are outdated, they said, including some that date back to World War II.

At the front, they are under constant Russian bombardment.

"They hit us with cluster bombs, then Grad rockets and then artillery again and again," one of the soldiers said. "They give us a cigarette break for a minute, and then it starts all over again."

Some of them said that in several days spent at the front, they didn't shoot their guns once. All they did was get shelled. What good is a rifle against long-range artillery, they ask.

"We didn't even understand where the Russians were shooting from. It was just raining down from above," one said. "It's not a war for infantry."

They say they want to fight, but only if they have good equipment and artillery and better battlefield tactics.

Residents in some areas are living under constant bombardment

Many civilians fled the Donbas after Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February. For those who stayed, life is hard — just how hard depends on how close they are to the front lines.

In villages and towns outside of Russian artillery range, there's still water and power, although gasoline is difficult to come by. At gas stations that still have fuel, the wait in line can last hours.

In places like Severodonestk, meanwhile, residents live under constant bombardment.

"It's basically been flattened," said one woman who only gave her first name, Olga.

She said she hid in the basement of her apartment building with fellow residents for weeks before she got pneumonia and had to move to the city's hospital.

After a month there, she was evacuated this week to Kramatorsk, a city 40 miles to the west but still within range of Russian forces.

She doesn't know whether she'll go back to Severodonetsk if the Russians capture the city and ultimately annex the territory.

"When you're sitting in the basement and hearing explosions, you think to yourself, 'let anybody come here, just let there be peace,' " she said. "We don't care who we live under. Just let it be peaceful."

Sitting in the back of a Red Cross ambulance in Kramatorsk as she waited to be evacuated further west, she teared up thinking about the home and city she'd fled.

"Every street had roses and chestnut trees," she said with a sigh. "Roses and chestnut trees."