Kyiv, Ukraine – Last Friday, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev appeared cornered as he sat next to his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, and Margarita Simonyan, head of the Kremlin-funded RT television network, which is sanctioned in the West.

The three were on the main stage of the International Economic Forum in St Petersburg, Russia’s former imperial capital and Putin’s hometown.

Simonyan asked the Kazakh leader about the “inevitability” and “legality” of what the Kremlin has dubbed a “special operation” in Ukraine – Europe’s largest armed conflict since World War II.

“There are different opinions about it,” Tokayev, Kazakhstan’s former foreign minister and the United Nations’ former deputy secretary-general, began diplomatically.

For about two minutes, he ruminated about international law, the UN’s Charter and the “incompatibility” of rights to territorial integrity and self-determination.

“If the right to self-determination is implemented worldwide, there will be over 600 nations instead of the 193 states that are currently UN members. Of course, that would be chaos,” Tokayev said.

And then he said something that seemed to have shattered Kazakhstan’s post-Soviet “strategic partnership” with its former imperial master.

“That’s why we won’t recognise Taiwan, Kosovo, [the breakaway Georgian regions of] South Ossetia and Abkhazia,” Tokayev said with a faint smile.

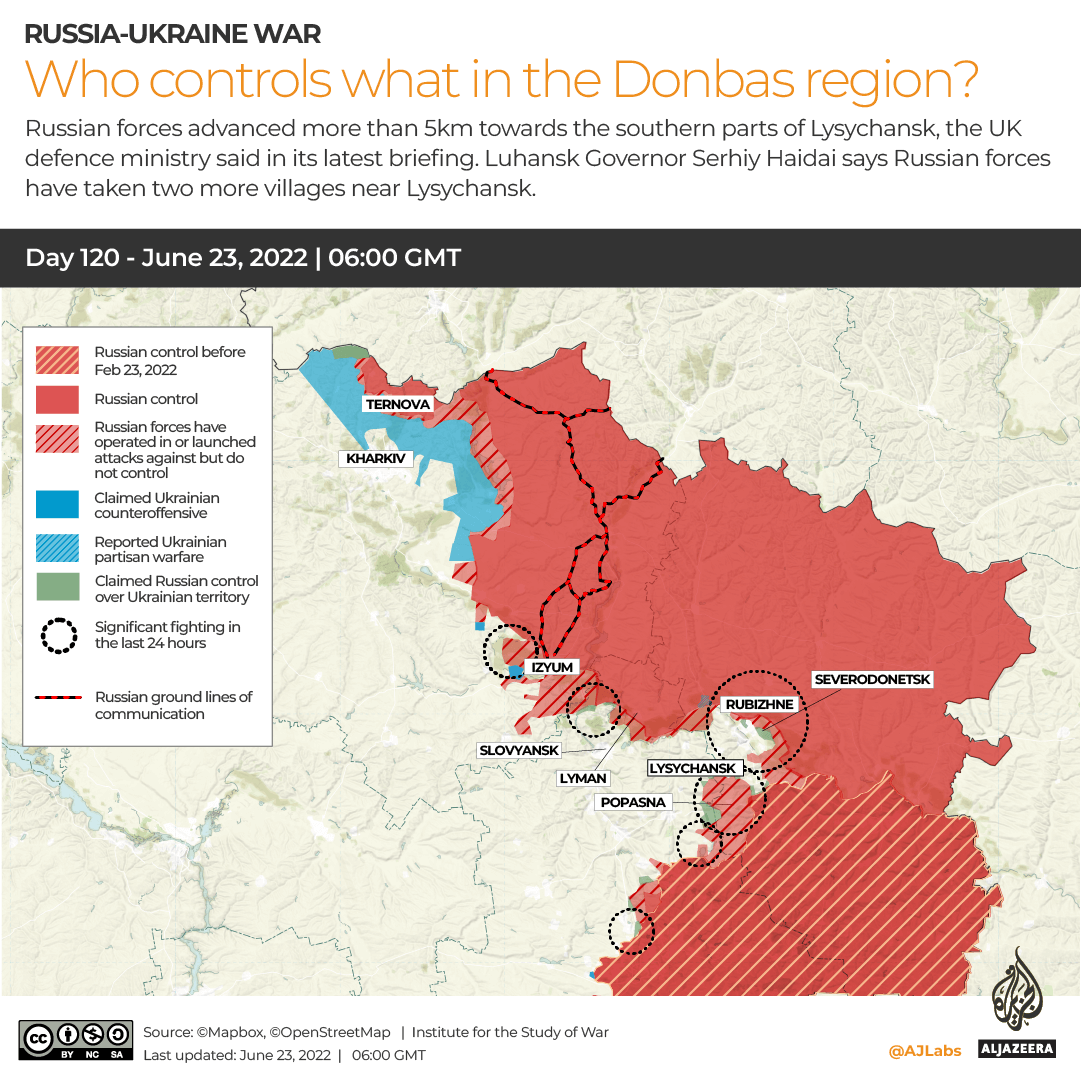

“Apparently, the same principle will be applied to the quasi-state territories that are, in our view, Luhansk and Donetsk,” the two breakaway regions in southeastern Ukraine, he said.

Both regions seceded in 2014 with Moscow’s military and financial backing in a war that killed more than 13,000 people and uprooted millions.

But the Kremlin recognised their “independence” only almost eight years later, on February 22, two days before invading Ukraine proper.

Tokayev’s words last week enraged many in the Kremlin.

A Russian lawmaker said Tokayev “challenged” Putin – and hinted that Moscow may invade Kazakhstan’s northern regions, which have a large ethnic Russian population.

“There are many towns with a predominantly Russian population that have little to do with what was called Kazakhstan,” Konstantin Zatulin told the Radio Moskva.

“I’d like Astana [the old name of the Kazakh capital, Nur-Sultan] not to forget that with friends and partners we don’t raise territorial matters and don’t argue. With the rest – like, for example, with Ukraine – everything is possible,” he said.

And many in Ukraine saw Tokayev’s spiel as a bold statement that signifies the “sunset” of Moscow-led political, economic and military blocs in the former USSR that include Kazakhstan.

“Kyiv noted the courage of Tokayev, who could say such words in Putin’s face,” Kyiv-based analyst Aleksey Kushch told Al Jazeera.

He said the Russia-Ukraine war – and the crimes committed by Russian servicemen in Ukraine – will result in Moscow losing influence in Kazakhstan and the four remaining “stans” of ex-Soviet Central Asia.

“The animal-like cruelty of the [Russian] empire on Ukraine’s soil has horrified even Russia’s traditional allies,” he said.

The mostly Muslim, resource-rich region of more than 65 million is stretched strategically between Russia, China and Afghanistan.

China and Turkey will fill the void – while “Russia’s soft underbelly from the Urals to the Altai [Mountains] will no longer be the ageing empire’s back yard,” Kushch said.

Dismembering Kazakhstan

Zatulin’s commentary did not mark the first time a Russian political figure questioned Kazakhstan’s very existence.

Shortly after Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, Putin claimed that Kazakhstan’s first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, “created a state on a territory that never had a state”.

“Kazakhs never had any statehood, he created it,” Putin told a pro-Kremlin youth group.

Six years later, another Russian lawmaker raised the stakes by claiming that Kazakhstan’s very existence was nothing but Moscow’s “gift”.

“Kazakhstan simply didn’t exist, northern Kazakhstan was uninhabited,” Vyacheslav Nikonov, a United Russia lawmaker said.

“And, actually, Kazakhstan’s territory is a big gift from Russia and the Soviet Union.”

Nikonov’s pedigree made his words sound especially ominous.

His grandfather, Vyacheslav Molotov of bottle-bomb “cocktail” fame, was the USSR’s foreign minister who signed a pact with Nazi Germany in 1939 to partition Poland – and pave the way to World War II.

“Nobody from outside gave Kazakhs this territory as a gift,” Tokayev retorted in an op-ed published in Kazakh newspapers in January 2021.

He mentioned Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan among the founders of what would become Kazakhstan.

At the time, Tokayev was widely seen as a figurehead handpicked by his predecessor Nazarbayev, who stepped down in 2019, but whose clan retained its influence in the oil-rich nation.

A year later, Tokayev asked for Moscow’s help during the largest protests in Kazakhstan’s post-Soviet history.

Thousands of young Kazakhs rallied in several cities toppling statues of Nazarbayev, clashing with police and storming government buildings.

Tokayev asked the forces of the Russian-led military alliance of the former Soviet states to restore order. Known as the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the bloc includes Russia and five ex-Soviet nations.

The CSTO troops did fly in and helped restore law and order – and the move was widely seen as a symbol of Moscow’s restored might in the former USSR.

As a result, Tokayev dramatically undermined the Nazarbayev clan’s clout and became a full-fledged, independent leader – all thanks to Putin.

And some in Kazakhstan see his remarks about the Ukrainian separatists as part of a well-staged political spectacle aimed at distracting the West’s attention.

“This is nothing but a game played to avoid sanctions on Kazakhstan,” a well-connected businessman in Kazakhstan’s financial capital, Almaty, told Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity.

“There are plenty of Russians who opened offices and run their money” via Kazakhstan to bypass the sanctions, he said.

A Kazakh analyst claimed that the spectacle had been worked out during Tokayev’s visit to Moscow in early February.

“The task was to show Tokayev as an independent and bold politician, a diplomat, who bravely retorts to questions and, at the same time, makes independent political steps,” Dimash Alzhanov told Radio Azattyk.

A Russian observer, however, sees no signs of foul play in Tokayev’s words in St Petersburg.

“I think this is a clear statement of Kazakhstan’s position, hardly a deal, what’s the sense in such a deal?” said Pavel Luzin, a Russia-based analyst with the Jamestown Foundation, a think-tank in Washington, DC.

“This is hardly a demarche – rather, a public reply to non-public efforts of the so-called Russian diplomacy,” he told Al Jazeera.