Arriving in the middle of the night at my Tbilisi hotel recently for a research project, I was told that my reservation had been rescinded and the hotel was now fully booked. A huge busload of Russian men had arrived at the hotel before me and were willing to pay more than the advertised price. I found it difficult to find a spare room in Tbilisi, but this was not surprising.

Days earlier the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, had announced a military mobilisation of 300,000 men, regardless of their military experience. Within hours, young Russians were packing their belongings and fleeing to Georgia, Turkey and other neighbouring countries.

On the Russian-Georgian border, cars have been waiting for hours in long lines of traffic. Though some of those fleeing may be against the war, most are just fearful for their own lives.

This contrasts with the first wave of Russian migrants into Georgia (which arrived in March 2022), who were mostly driven by economic factors. Many middle-class Russians fled after sanctions were imposed, but were not necessarily against the conflict or Putin’s regime. These Russians have been welcomed by the Georgian government, led by the Georgia Dream Party, which has a no-irritation policy with Russia – introduced after 2008 to try to smooth relations with Moscow.

The same can’t be said for the largely pro-Ukrainian Georgian population. However, there have been some issues. Russian migrants have caused a housing crunch, with rent costs doubling since March. Some Russians are keeping a low profile, even pretending to be Ukrainians.

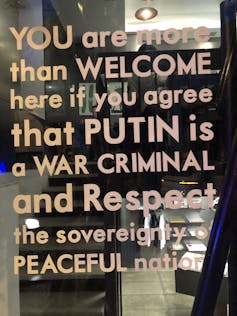

In some cases, Georgians have verbally attacked Russians, while many restaurant and bar owners have asked Russians to sign an oath denouncing the war. Some of the graffiti that covers the walls of Tbilisi makes clear what the Georgian people think of Putin.

But Georgians are also concerned that the constant chatter in Russian is not just coming from civilians. There are reports of Russians working for Russia’s security service, the FSB, spying on new arrivals in Georgia.

Political divide

But the conflict has caused far greater problems for Georgia than just migration. The Georgia Dream Party, (officially led by former business executive Irakli Garibashvili and run behind the scenes by former prime minister and Georgia’s richest man, Bidzina Ivanishvili) has not been critical of Russia. It has also refused to levy sanctions on Ukraine or offer Ukraine any support – due in part to fears of Russian retribution.

By contrast, the Georgian public is very staunchly pro-Ukrainian – even leading to mass protests against Georgia’s inadequate support for Kyiv.

In spite of this, the ruling party has propagandised its ability to maintain a relationship with Russia and avoid war as its main asset for the Georgian public. The Georgia Dream Party claims that the opposition (which is tied to imprisoned ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili, a former governor of the Odesa oblast in southern Ukraine) wants to provoke Russia into invading. The fears of a Russian invasion are not unwarranted. Russia invaded in 2008 and Russian troops are still stationed about 25 miles from Tbilisi.

Fear of invasion

No matter what Georgia does, it appears stuck in a catch-22 situation. Many people in Tbilisi told me that if the war goes badly for Russia, in order to save face, Putin may go for a quick invasion of Georgia. Georgia’s government has not invested in its military, believing that a build-up might provoke Russia further. But there are also fears that if the war starts to go better in Russia, Putin will be ambitious to conquer other lands.

Russia has never been comfortable with the idea of the classical nation-state. As Putin has made clear he has imperial ambitions, and there are suggestions that he wants to restore the former Soviet Union.

Attacking a Nato country is highly unlikely at this point, but there is always a possibility of conflict in the Caucasus. Georgians believe that Russia has had a history of using force to defend Russian minorities in other territories and countries. As more Russians flee to Georgia, the government and public face the challenging task of not wanting to give Putin a reason to invade.

For Georgia Dream leader Bidzina Ivanishvili, the situation with Ukraine is also personal. Though his rival and former president Mikheil Saakashvili is currently a political prisoner, he represents Ivanishvili’s main rival. Saakashvili is perceived as an important figure in Ukraine – he is close to Volodymyr Zelensky and is firmly anti-Russian.

By contrast, Ivanishvili may be compromised by his business ties to the Russian government and Russian political elites, and has concerns about Zelensky winning. In spite of public opinion, Georgia is one of the few countries whose government has publicly attacked Zelensky and his administration.

For most Georgians, the memories from the 2008 war with Russia are still fresh. The public wants to support Ukraine while also avoiding another invasion, which would likely directly target its bustling capital of Tbilisi. Georgians fought valiantly but were overwhelmed by Russian aerial bombing, and thus want to avoid war at all costs. But Georgian scholars feel the country has very little influence over its own destiny. Instead, for most Georgians they see their future directly tied to the outcome in Ukraine.

Natasha Lindstaedt ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.