News reports this week quoted anonymous sources from the US and Ukraine that the first six F-16 jets had been supplied by the Netherlands to the war-torn country and that more were expected to be supplied by Denmark.

Video footage apparently showing F-16s flying above Ukraine have been doing the rounds. It is thought that the Ukrainian air force will be supplied with 20 of the jets this year of a total of 80 pledged by Kyiv’s western allies. Ukrainian officials have said that the country will need at least 300 warplanes including 130 F-16s in order to achieve an adequate air defence.

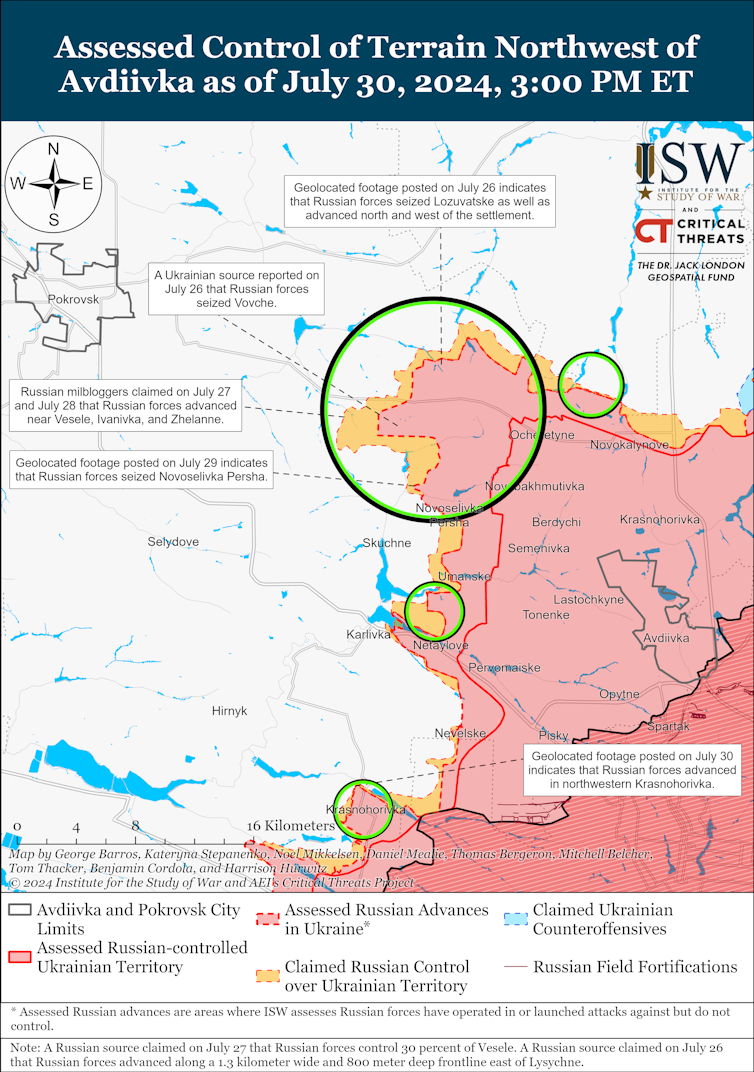

Whether the new arrivals are too little and too late remains to be seen. Russian troops continue to make steady advances, particularly in areas around Donetsk as their summer offensive gets properly underway.

The key Russian objective appears to be a city called Pokrovsk, about 70km west of Donetsk, which – as Dara Massicot of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace said on X (formerly Twitter) on July 31 – is a “very critical node in that region and if they take it then they get control over critical routes and then the whole region there in Donetsk is at risk”.

Since Vladimir Putin sent his war machine into Ukraine on February 24 2022, The Conversation has called upon some of the leading experts in international security, geopolitics and military tactics to help our readers understand the big issues. You can also subscribe to our fortnightly recap of expert analysis of the conflict in Ukraine.

There have been reports from the Institute for the Study of War of at least five mechanised assaults, which are at present being resisted by Ukrainian units.

Meanwhile Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky is still desperately trying to persuade Ukraine’s western allies to give him permission to use their longer-range missiles against targets inside Russia. This would deny Ukraine’s enemy the luxury of being able to launch air attacks and bombard the country at will and without danger. “Unfortunately, our partners are still afraid of this,” Zelensky lamented.

So it’s perhaps unsurprising that many Ukrainians are coming around to the idea that it’s worth making territorial concessions in return for a speedy ceasefire and peace deal with Russia, reports Stefan Wolff.

Wolff, an expert in international security at the University of Birmingham who regularly contributes his analysis about the war in Ukraine, says that a recent poll found that almost one-third of Ukrainians are now prepared to make territorial concessions to Russia if this brings the Russian war of aggression to a swift end and preserves their country’s independence.

In the previous poll along these lines, taken in the summer of 2023, only 10% – or fewer – had been willing to give up land for a peace deal. But the failure of Ukraine’s spring-summer offensive last year and the relentless, grinding bad news from the front is taking its toll.

Wolff believes that the outcome will have a lot to do with the relative positions of Washington and Beijing. China’s president, Xi Jinping, seems to have grown more supportive of Vladimir Putin over the two years of war. But the fear that November’s presidential election in the US would result in a Donald Trump presidency would have depressed many Ukrainians, given that Trump and his pick for vice-president, J.D. Vance, have signalled they are less likely to support Ukraine the way that Joe Biden has. Of course, a victory for Kamala Harris in November could change all that.

Read more: One-third of Ukrainians would give up land for peace – but it's not as simple as that

A fortnight ago we discussed the success of Ukraine in defeating Russia’s Black Sea fleet, sinking more than a third of its ships and forcing the remainder to relocate from its traditional anchorage in Sevastopol in Crimea to safer waters in the port of Novorossiysk.

Here, Glynn Williams, an expert in warfare at UMass Dartmouth in the US, looks in more detail about what the Battle of the Black Sea can tell us about how weaker powers can take advantage of innovative thinking and new technology to defeat more powerful opponents.

Williams considers the importance of the Magura-V5, the world’s first combat-deployed sea drone, designed and built by Ukranian engineers. He believes this “explosive-laden vehicle” made a material difference in the sea battle by doing “what many thought impossible: travel long distances across stormy seas, undetected by radar, and deliver 500 to 700 pounds of explosives to distant targets”.

Read more: How the Ukrainians – with no navy – defeated Russia's Black Sea Fleet

A ‘holy war’?

Pretty much everyone who has ever started a war has claimed that God is on their side, although – sensibly – the 17th-century French wit Roger de Rabutin, noted that “providence is always on the side of the big battalions”. Voltaire subsequently refined this – presumably as weaponry became more sophisticated – into: “God is not on the side of the big battalions, but on the side of those who shoot best.”

So it came as little surprise when Putin enlisted the help of the head of the Russian Orthodox church, Patriarch Kirill, to declare the illegal invasion of Ukraine by its far larger neighbour as a “holy war”. Moscow’s chief rabbi, Pinchas Goldschmidt, meanwhile, when urged to make a similar statement to encourage Russia’s Jews into service, promptly fled the country. Meanwhile, Said Ismagilov, the mufti of the Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine and one of the country’s most important Muslim leaders, joined up tofight the invaders.

Jennifer Mathers, an expert in Russian political and cultural history at the University of Aberystwyth, gives us this fascinating analysis of how the different faith leaders in Russia and Ukraine have responded to the conflict.

It’s an intriguing patchwork of motivations, both political and historical. There are the Crimean Tartars, Muslims who are fighting for Ukraine in the memory of their lost homeland. Then there are Chechens, fighting on both sides. Some of them are loyal to Putin’s close ally, Ramzan Kadyrov, and are fighting for Russia. Others see the war as a chance to deal a bloody nose to Russia and maybe get one step closer to gaining independence for their homeland.

Read more: Ukraine war: religious leaders are playing an important (and unusual) role

War on nature

What too often gets lost in the fog of war is the effect the conflict is having on a country’s wildlife. Before the war there were approximately 5.5 million cats and 750,000 dogs in Ukraine. Many of these have been killed or abandoned by their owners as they fled, causing a huge increase in the number of strays.

An estimated 25% of Ukraine’s protected nature areas have been occupied by Russian forces, wreaking havoc with the country’s ecosystems. Tragically, some biologists believe tens of thousands of Black Sea dolphins have been killed.

Iryna Skubii, an expert in human-environmental relationships in Russia and Ukraine, argues that there’s a case to be made against Russia for “ecocide”. This is not yet an offence in international law, although Belgium recently voted to make it an offence at both national and international levels. The hope is that other countries will follow suit.

Finally, just as this newsletter was going to print, the news has broken that Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich will be released as part of a multi-country prisoner swap.

Clearly no one person’s life is more important than another’s in this awful conflict which has brought so much suffering to so many. But as a fellow journalist I want to express solidarity with Gershkovich. Watch out for more in-depth coverage of this in days to come.

Ukraine Recap is available as a fortnightly email newsletter. Click here to get our recaps directly in your inbox.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.