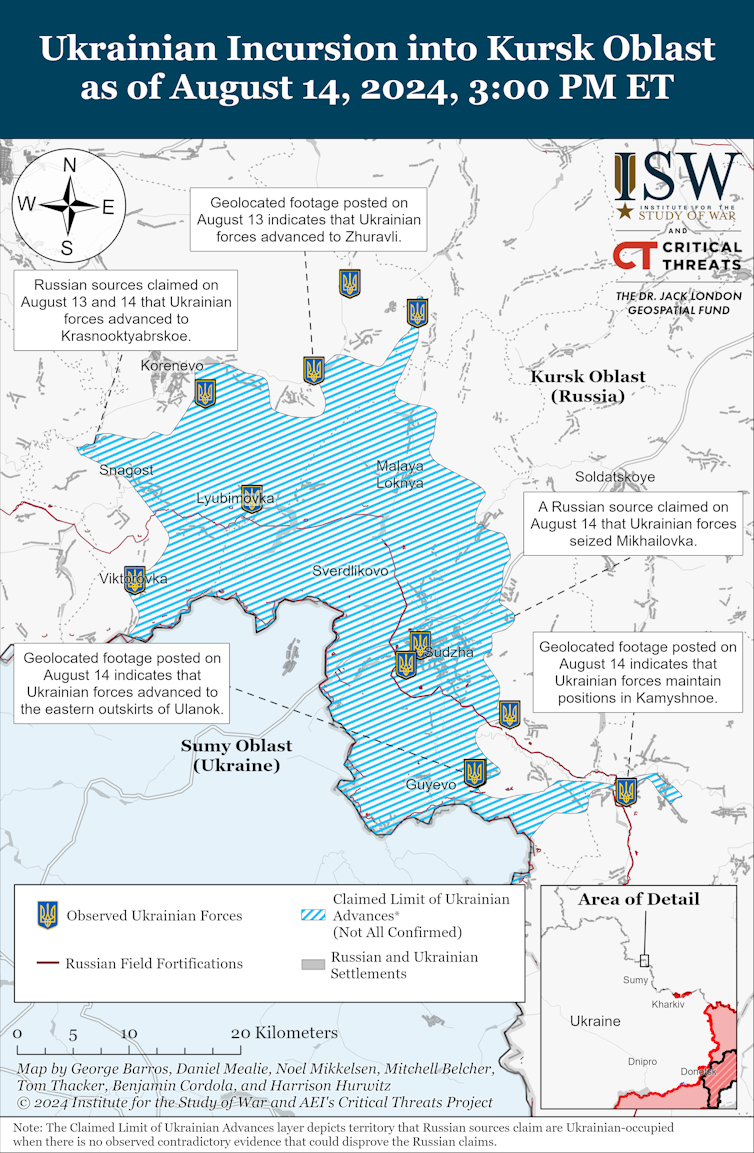

Social media was buzzing earlier this week with restaurant reviews from the Kursk region of Russia, written by Ukrainian troops. They were clearly enjoying the fact that after months of grinding retreat in the face of a relentless Russian advance, they now found themselves on the other side of the border.

Their lightning-fast incursion onto Russian soil had taken the Russian army by surprise. By Wednesday evening, they controlled about 1,000 square kilometres of Russian territory. One of the facetious messages read (in translation):

A group of us will be visiting in a few days and were wondering if you have parking for about a dozen tanks? Please bear in mind we have British Challenger II tanks, which are much bigger than Russian ones.

Russian border guards had reportedly raised the alarm that Ukrainian units were massing near the border. But neither the Russian commanders, nor pretty much anyone else watching the conflict closely, believed that Ukraine – under pressure along the frontline in Donbas – had the manpower to launch an operation of this kind, writes Patrick Bury, a reader in security at the University of Bath.

Since Vladimir Putin sent his war machine into Ukraine on February 24 2022, The Conversation has called upon some of the leading experts in international security, geopolitics and military tactics to help our readers understand the big issues. You can also subscribe to our fortnightly recap of expert analysis of the conflict in Ukraine.

Bury, who came to academia via the British army and a role as an analyst with Nato, specialises in warfare and counter-terrorism. He believes that surprise was the key to the success of the incursion, ensured by careful operational security.

It would have been an operation months in the planning, writes Bury, rapidly establishing and maintaining strong air defence and electronic warfare bubbles over their advancing troops. The effect has – so far at least – been a stunning success. It’s the most Russian territory to be occupied by another country since the second world war, and Russian officers who have been called in from other theatres of operation have reportedly spoken of how difficult it will be to dislodge the invaders quickly.

Media reported a “top Ukranian official” as saying that the objective of the incursion is to stretch the positions of the Russians and inflict the maximum casualties. The operation was also designed to raise morale among the Ukrainian public and military alike, something that – judging by the social media messages reported here – has certainly been achieved.

There’s also a strong possibility that Volodymyr Zelensky had his military commanders plan the operation in the belief that Donald Trump was more than likely to win the US presidential election in November. On Tuesday afternoon the Ukrainian president referred to the capture of 74 communities as part of his country’s “exchange fund”.

In the event of Trump winning in November, halting aid and forcing Ukraine to the negotiating table, these settlements and their inhabitants could be valuable bargaining chips.

Read more: Ukraine war: Kursk offensive has taken the war into Russia and put Putin on the back foot – for now

Pressure on Putin

Vladimir Putin, meanwhile, has been quick to label the operation as a “provocation requiring a counter-terrorist response”. Stefan Wolff, an expert in international security based at the University of Birmingham, believes that this week’s operation will pile fresh pressure on the Russian leader.

Interestingly Putin was quick to point at Ukraine’s Nato allies, saying that “the west is fighting us with the hands of the Ukrainians”. This, says Wolff, is in line with Putin’s repeated insistence that Ukraine (which, remember, he believes isn’t even a real country in its own right) is merely the agent of Russia’s enemies in the US and Europe.

This of course makes the reference to British Challenger II tanks in the facetious Ukrainian social media message all the more interesting. UK prime minister, Keir Starmer, has made it clear that, apart from the long-range Storm Shadow cruise missiles, Ukraine is free to use the weapons supplied by Britain in any way it chooses.

Throughout the course of the war, Putin has reacted to any talk of the use of western weapons inside Russia with threats of escalation. Thus far, neither the Russian leader, nor his faithful proxies such as Dmitry Medvedev, have issued the standard hint about Russia’s formidable nuclear arsenal. But even if the Russian leader does threaten escalation, Wolff believes it is unlikely to come at this point.

The possibility of negotiations happening sooner rather than later means there would be very little to gain from forcing a confrontation with Nato, something that could easily get out of hand and trigger Article 5, requiring the alliance to act collectively and raising the possibility of full-scale war.

Europe arms itself

Meanwhile a deal agreed at the recent Nato summit will see a new generation of American medium-range missiles stationed in Germany. This will reportedly involve Tomahawk cruise missiles, SM-6 ballistic missiles and a new generation of hypersonic systems currently under development.

A lot has changed since the US and Russia signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in 1987, writes Christoph Bluth, an expert in international security at the University of Bradford. This agreement, made between the then US president Ronald Reagan, and the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, pledged to do away with all missiles with ranges of between 500kms and 5,500kms.

Donald Trump pulled the US out of the treaty in 2019 and now, in the face of Russian aggression, Europe is arming itself again. Nato countries are allocating more of their GDP to defence as demanded by the US. And various European countries are upgrading what were originally purely defensive alliances, such as the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI) into agreements with what appear to be more offensive capabilities, such as the European Long-Range Strike Approach (ELSA), which aims to enable the development of European long-range strike capabilities to complement the US-German agreement.

Read more: Fears of a fresh arms race as US to deploy missiles in Germany that can hit targets in Russia

Ukraine’s heritage matters

Over the decades, Russian, and previously Soviet, leaders have attempted to expunge any sense of specifically Ukrainian art, culture, language and history. It’s been the Kremlin’s way of trying to establish that Ukraine doesn’t exist as a separate entity, but is part of Russia.

But Ukraine has always had a strong sense of its own cultural identity, as amply illustrated by an exhibition on at the Royal Academy in London.

Jenny Mathers went to see the show, Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s to review the artworks and their history, in the context of modern history and politics. That many works had to be evacuated from Kyiv while it was under fire from Russian artillery makes the show even more relevant.

Mathers details here how Putin’s aim to wipe out symbols of Ukrainian heritage is just part of a longer Russian mission. But, she says hopefully, the world is now far more aware of it than in previous decades. She believes that “at a time when Ukrainian cultural history is being threatened with erasure, educating ourselves about that history is both a practical and a symbolic act of support for Ukraine”.

Read more: Evacuated artworks exhibit details attempts to wipe out Ukrainian culture – and shows what survives

Ukraine Recap is available as a fortnightly email newsletter. Click here to get our recaps directly in your inbox.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.