On 15 April 2022, I travelled to Ukraine, intending to stay there for a month. A simple question underpins my research trip: how do we behave when the world collapses around us? We oppose it with weapons, mutual help, aid, and humanitarian work. We watch it in disbelief. We flee it. We take action.

Throughout my month-long trip, I endeavoured to document the day-to-day experience of the war, based on accounts from civilians who are reacting to this overwhelming chain of events.

War as an experience of the world collapsing

War is, above all else, an experience of the world collapsing. It is the loss of loved ones; it is exile and destruction. The disappearance of reference points that usually structure daily life puts people’s psyche to the test. The world’s collapse is not just a tragedy – it gives rise to a host of unexpected emotions in every one of us. That is undoubtedly what gives war its paradoxical texture: it fascinates people as much as it repulses them. In war, life is diminished in tangible terms, yet ordinary people discover individual and collective powers within themselves. War affects life as much as it inspires people to turn to others. It is an experience of decay and altruism. It puts each person squarely back in the world, in a world that is collapsing.

War unsettles the mind. It requires certainty. Its motives do not square with any sense of nuance. You cannot resist using “however” or “whys”. Otherwise, you would resist hesitantly, and hesitation saps bravery. One unit of meaning clashes with another. “Ukraine supporters” and “Russia supporters” trumpet their certainties, tell their version of history, cling to their geopolitical convictions, and explain the irrational: Russia’s invasion. In this torrent of voices, as confident as they are contradictory, meaning freezes. The longer the war lasts, the more meaning stiffens. Ethnography tries to salvage what geopolitics and ideologies destroy: war is also the matter of ordinary people. It affects their existence radically.

War fantasies

Whenever an ethnographer travels to a war zone, the questions that haunt them are always the same: What is actually happening? What caused the war? Their perspective is rooted in the field: they report on local situations, the general atmosphere, a few tales told here and there, the subjective experience of the people they meet. Intellectual honesty compels them to keep quiet about all the rest, including sweeping questions about the war’s origins and the geopolitical games that go with it. They stick to a vague response: there is a whole period that paved the path to war. Nothing guarantees them that the local viewpoints they have collected reflect the overall situation. History is also made from the bottom up, by the way ordinary civilians respond to a situation that overwhelms them and justify their disobedience.

Of course, war has its perils. But it comes with entrenched fantasies. Whoever goes to a war zone, whether to record the situation or take part in humanitarian work, makes their loved ones uncomfortable. They all imagine the person – even though they have no links to the situation they are about to engage with – will witness many battles, the forces of resistance, and cruelty of war. Undoubtedly, many adventures await them, and danger will threaten their life. They are honoured, however tacitly, for their bravery as they choose to go to that spot in the world where history is being made. These fantasies make farewells to their loved ones difficult. In the absence of any better words, a few sober, modest phrases see them off: “Have a safe journey. Be careful. Come back in one piece.”

It is good to sense this sudden affection, as if your life had to be endangered for emotional bonds to express themselves. Your pride is puffed up, as much as it is undeserved. This delusion does not stand the test of reality. The horrors of war certainly exist. But a journalist, researcher, or aid worker rarely sees them. They witness them fleetingly. Their lives are supervised. They belong to a category whose lives are especially worthy of protection. Their bodies are seldom exposed to the harshness of war.

(Dis)organising one’s departure

War foists the concrete reality of experience on the romantic version of it. To start making such a trip real, you need to organise your departure. This means gathering information and contacts: Where should I go? Who should I meet? How can I find a trustworthy fixer, someone who can guide me on site, connect me with fighters and act as an interpreter? This is a real job. War opens up careers, and a fixer happens to be one of them. The higher the demand, the higher their rates. Today, it is hard to find a fixer who charges less than 250 euros per day.

I was on Maiden Square during the 2014 Maiden Revolution. The contacts I was able to make during my stay there were crucial, but not numerous enough to base this specific research trip upon. Searching for information is arduous, especially since mutual help among those who report on the conflict is often weak, mainly because each reporter’s life is plunged into disorder and uncertainty. A plan devised one evening is disowned or altered the next day. Each reporter is consumed with the prospects of possible meetings, relevant places they could go to, people with whom it would be advantageous to work with. Uncertainty is all the more taxing, as our time on site is brief and we have to faithfully reflect the situation and find a subject. So it is better to activate our contacts once we are on site: “I’m in Kiev!”

My presence on the ground confirms I am a valid interlocutor. But there is also a less noble reason – competition between journalists or researchers. Efforts to develop a network come at a cost. Competition is real. Many of my messages to people on site remained unanswered. War and the challenges of documenting it do not always inspire the solidarity we might expect when a population is threatened with extinction. War calls for a certain detached attitude: to understand and to go with the flow of encounters. To go with the flow is the way to go if one wants to stay open.

What should you pack?

Little is written about the practical details of such journeys. What should you pack? As a rule, you should travel light to make it easier to get around. But one month is quite a long time. I packed ten or so items of underwear, three tee-shirts, a pair of jeans, a jumper, twenty batteries for my voice recorder, a computer, cash, a bulletproof vest (in France, a level-three bulletproof vest costs more than 2,000 euros) which I borrowed from Reporters Without Borders, a helmet, and four notebooks – one for writing down my thoughts, and three for writing down what the people I meet tell me.

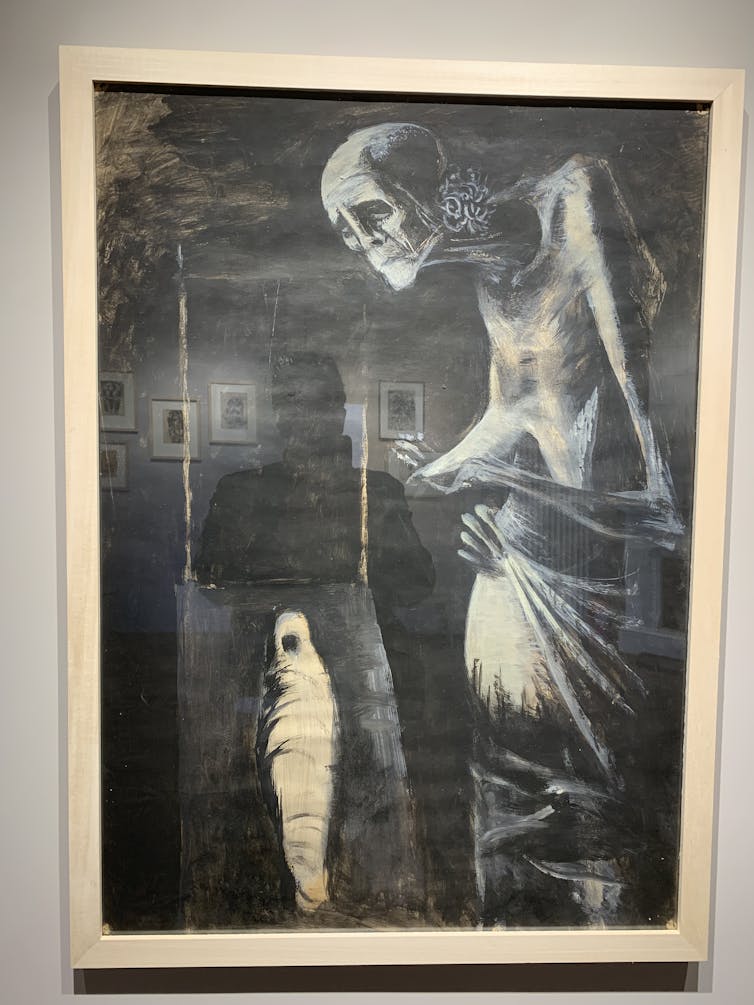

I also brought a few books, although I had a hard time picking which ones. I opted for literature: Promise at Dawn by Romain Gary, Sankhara by Frédérique Deghelt, The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Richard Flanagan. I knew nothing about these novels, about their quality or power, but literature whispers words and helps get a perspective in the fog of war. At the last minute, I also took along Le Témoin jusqu’au bout (The Witness to the End) by French philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman.

On-the-ground research in war zones does not let itself be tamed by rationalisation. It is useful to a have a network that can inform you about the situation, ease administrative procedures, and put you in touch with the right people. But you need to recognise one permanent feature: whereas war gives those who take part in it the feeling they have a hold over the world until it collapses, an ethnographer sees the world escape all subjugation. This kind of journey is paved with uncertainty. It is made up of naive foresight and plans called off as quickly as they are drawn up.

Bohdan, 21

I arrived in Lublin, Poland, on 15 April. At the airport, I found out the airline had lost my rucksack. I was stunned and filled with anxiety. I had planned to cross the border that same day. It was the first stage of my journey: getting into the country as quickly as possible. After paying for a hotel room, I went over to a taxi to get to the train station so I could find out about the next trains leaving for Ukraine. This incident had an unexpected consequence that was very fortunate. I met Bohdan, a 21-year-old student who worked as a taxi driver to finance his studies. Bohdan was Ukrainian. I told him about my plans. He decided to help me find the best way to get into Ukraine. At the train station, he did not just drop me off but went along with me to help me find information. I learned the next train for Kyiv would be next Friday – in one week’s time. “Everyone’s going back to Kyiv”, the ticket office worker explained.

I was somewhat disheartened. Bohdan suggested going to the bus station. We checked out the next departures. Because of the Easter holidays, there would be no bus leaving before Wednesday 20 April. I could not wait that long. Bohdan took me back to Lublin city centre. He turned down my money: “I’m doing this for Ukrainians. If it was your firm paying, I’d have accepted the money, but in this situation I won’t.” Bohdan had been in Poland for two years. His family was still in Ukraine. At 21, he already had a taxi business and three cabs. He actually yearned to go with me to Ukraine. He would have liked to fill up his car with equipment he could take to his family or people on site. He told me, “I’m impulsive. I like it when life changes. I’m eager to give my existence a new direction.”

I sensed him hesitating. One does not prepare for this kind of journey in just a few hours. I was in too much of a hurry. My airline found my bag. In the end, he dropped me off at the border in his car. A Ukrainian family agreed to drive me to the other side of the border. I arrived in Lviv on 17 April.

Progress has entered a pact with barbarity

I very much doubt these details will enlighten people about the war. They seem trivial and vain, in light of a people being bombed and forced into exile, forced to endure the loss of its world. That is all true. But ethnography works along the margins, in the details.

It contrasts fantasies with the tangible reality of ordinary life’s complications. Given all the anecdotes told here, you might wonder whether exploring such a field is really worth a researcher’s time. The answer is as trivial as the anecdotes. We need to understand what is happening and what we are becoming. Georges Didi-Huberman tells us that Sigmund Freud, in his last work, Moses and Monotheism, tackled the issue with alarming simplicity, just as he was witnessing the dawn of the Third Reich. In his very last preface, he wrote:

“We are living in a particularly strange era. We are discovering with surprise that progress has entered into a pact with barbarity.”

His take still resonates today. There are many ways to resist warmongering passions. One of the most important is to reflect, to question what is happening, to observe so as to find in it something like a “content of historical truth”.

Translated from the French by Thomas Young for Fast ForWord.

Romain Huët does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.