A friend of mine, usually an intensely optimistic pro-Ukraine analyst, returned from Ukraine last week and told me: “It’s like the German Army in January 1945.” The Ukrainians are being driven back on all fronts – including in the Kursk province of Russia, which they had opened with much hope and fanfare in August. More importantly, they are running out of soldiers.

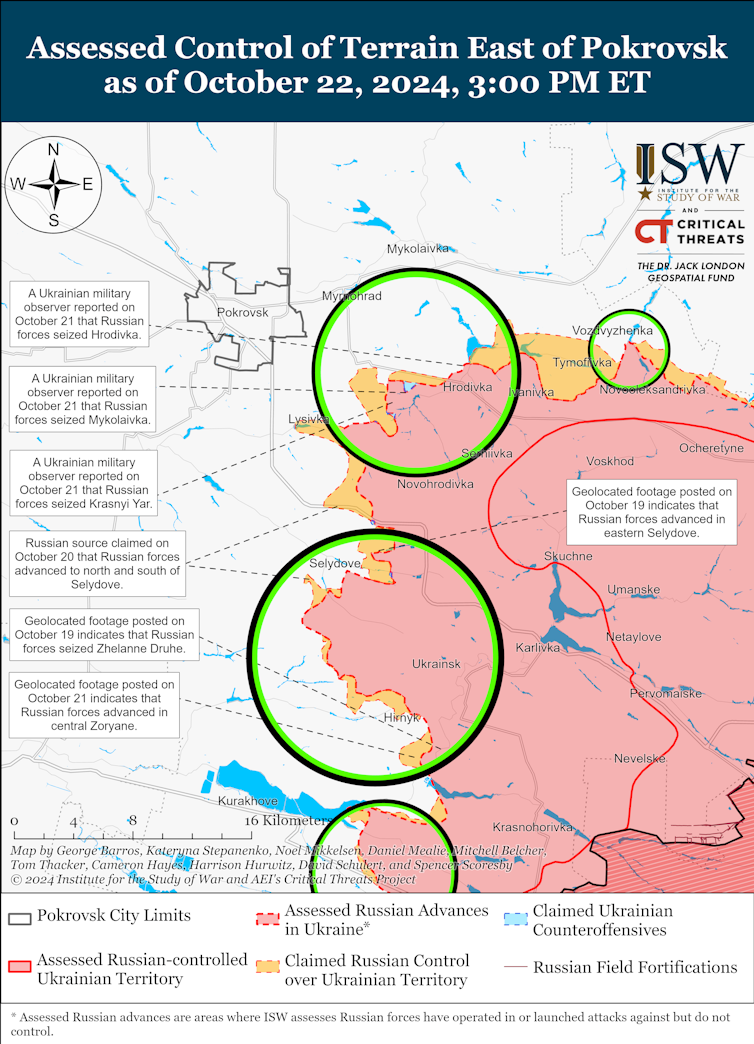

For most of 2024, Ukraine has been losing ground. This week, the town of Selidove in the western Donetsk region is being surrounded and, like Vuhledar earlier this month, is likely to fall in the next week or so – the only variable being how many Ukrainians will be lost in the process. Over the winter, the terrible prospect of a major battle to hold the strategically significant industrial town of Pokrovsk beckons.

Ultimately, this is not a war of territory but of attrition. The only resource that counts is soldiers – and here the calculus for Ukraine is not positive.

Ukraine claims to have “liquidated” nearly 700,000 Russian soldiers – with more than 120,000 killed and upwards of 500,000 injured. Its president, Volodymyr Zelensky, admitted in February this year to 31,000 Ukrainian fatalities, with no figure given for injured.

The problem is these Ukrainian totals are apparently believed by western officials, when the reality is likely to be very different. US sources say the war has seen 1 million people killed and wounded on both sides. Crucially, this includes a growing number of Ukrainian civilians.

Low morale and desertion, as well as draft-dodging, are now significant problems for Ukraine. These factors are exacerbating already serious recruitment issues, making it hard to supply the front lines with fresh troops.

A dreadful debate is taking place in Ukraine. The question revolves around whether to mobilise – and risk serious casualties to – the 18-25 age group. Due to economic pressures in the early 2000s, Ukraine suffered a major drop in its birth rate, leaving relatively few people now aged between 15 and 25. Mobilisation and serious attrition of this group may be something Ukraine simply can’t afford, given the already serious demographic crisis the country faces.

And even if this mobilisation does go ahead, by the time the necessary politics, legislation, bureaucracy and training have run their course, the war may be over.

Victory look impossible

History knows of no example where taking on Russia in an attritional contest has proved successful. Let’s be clear: this means there is a real possibility of defeat – there is no sugar-coating this.

Zelensky’s maximalist war aims of restoring Ukraine’s pre-2014 borders, along with other unlikely conditions – which were unchallenged and encouraged by a confused but self-aggrandising west – will not be achieved, and the west’s leaders are partly to blame. Ill-advised wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East left western armed forces hollow, poorly armed, and entirely unprepared for a serious and prolonged conflict, with ammunition stocks likely to last weeks at best.

European promises of millions of artillery rounds have failed to materialise – only 650,000 have been supplied to Kyiv this year, whereas the North Koreans have supplied at least twice that to Russia.

Only the US has significant stocks of weaponry in the form of thousands of armoured vehicles, tanks and artillery pieces in reserve – and it is unlikely to change its policy of drip-feeding weapons to Ukraine now. Even if such a decision is made, the lead-time for delivery will be years, not months.

In a confidential briefing I attended recently given by western defence officials, the atmosphere was downbeat. The situation is “perilous” and “as bad as it has ever been” for Ukraine. Western powers cannot afford another strategic disaster like Afghanistan which, in the words of Ernest Hemingway (aptly quoted by the strategist Lawrence Freedman), happened “gradually, then suddenly”.

There will be no decisive breakthrough by Russia’s army when they take this town or that (say, Pokrovsk). They haven’t the capability to do it. So, there won’t be a collapse – no “Kyiv as Kabul” moment.

However, there are limits to the losses Ukraine can take. We do not know where that limit lies, but we’ll know when it happens. Crucially, there will be no victory for Ukraine. Unforgivably, there is not, and never has been, a western strategy except to bleed Russia as long as possible.

More fundamentally, two ancient ethical questions governing whether a war is just must now be asked and answered: whether there is a reasonable prospect of success, and whether the potential gain is proportionate to the cost.

The problem, as so often before, is that the west has not defined what it considers a success. The cost, meanwhile, is becoming all-too clear.

To have clearly defined its goals and limits would have constituted the beginnings of a strategy – and the west isn’t good at that. Nato’s leaders now need to move quickly beyond meaningless rhetoric or anything that smacks of “as long as it takes”. We saw where that led in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya.

We need a realistic answer to what something like a “win”, or at least an acceptable settlement, now looks like – as well as the extent to which it is achievable, and whether the west is really going to pursue it. And then for western leaders to act accordingly.

A starting point could be accepting that Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk are lost – something an increasing number of Ukrainians are beginning to say openly. Then we need to start planning seriously for a post-war Ukraine that will need the west’s suppport more than ever.

Russia cannot possibly take all, or even the bulk of, Ukraine’s territory. Even if it could, it could not possibly hold it. It is amply clear there will be a compromise settlement.

So, it is time for Nato – and the US in particular – to articulate a viable end to this nightmarish ordeal, and to develop a pragmatic strategy to deal with Russia in the coming decade. More importantly, the west must plan how to support a heroic, shattered – but still independent – Ukraine.

Frank Ledwidge does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.