The UK government on Wednesday announced plans to axe 92 House of Lords seats retained for hereditary lawmakers, resurrecting reform of the unelected chamber started under Tony Blair's Labour government in the 1990s.

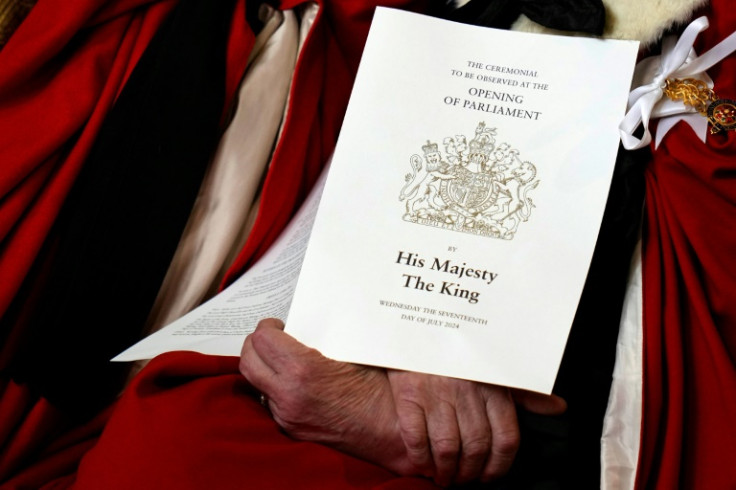

King Charles III, opening the first parliamentary session after Keir Starmer's general election win for Labour, said removing the peers' right to sit and vote in the Lords was part of "measures to modernise" Britain's uncodified constitution.

Labour won the July 4 election by a landslide, returning it to power for the first time since 2010, allowing it to put its manifesto pledges into law, including the much-touted Lords reforms.

Parliament's unelected upper chamber has long been subject to demands for reform to make it more representative and less "a chamber festering with grotesques and has-beens", as one newspaper columnist famously described it in 2022.

But the extent of Labour's plans remain unclear.

The scrapping of the hereditary peers -- the hundreds of members of the aristocracy whose titles are inherited -- has been described as a "first step in wider reform".

"The continued presence of hereditary peers in the House of Lords is outdated and indefensible," the government said in briefing notes accompanying the King's Speech.

Comprising around 800 lawmakers, the House of Lords is comfortably larger than any other equivalent in a democracy.

Its members, whose current average age is 71, are mostly appointed for life.

They include former MPs, typically appointed by departing prime ministers, along with people nominated after serving in prominent public- or private-sector roles, and Church of England clerics.

The primary role of the centuries-old chamber is to scrutinise the government.

It cannot override legislation sent from the popularly elected House of Commons, but it can amend and delay bills and initiate new draft laws.

That job occasionally propels the Lords into the political spotlight, such as during its recent delays to the previous Conservative government's contentious Rwanda deportation plan -- quickly scrapped by the new government.

Like the Commons, the Lords has specialised scrutiny committees.

The new government's planned legislation revisits the House of Lords reform agenda that Blair's Labour government initiated in the late 1990s.

His government had intended to abolish all the seats held by hundreds of hereditary members who sat in the chamber at that time.

But it ended up retaining 92 in what was supposed to be a temporary compromise.

"25 years later, they form part of the status quo more by accident than by design," said the briefing from Prime Minister Keir Starmer's government.

"No other modern comparable democracies allow individuals to sit and vote in their legislature by right of birth," it added.

"Holding membership of a seat within a Parliament on a hereditary basis is incredibly rare."

The government said the reforms were in part motivated by the gender imbalance of hereditary peers -- currently all male, because most peerages can only be passed down the male line.

The rest of the House of Lords fares better, with 242 of other members -- 36 percent -- female.

Starmer's new administration also argues that hereditary peers are too politically "static" for a democracy.

Of the 92 seats allotted for them under the 1999 reforms, 42 are for Conservatives, 28 for so-called crossbenchers, three for the Liberal Democrats and just two for Labour.

Meanwhile 15 are elected by the entire chamber from the hundreds of hereditary peers that exist in the UK.

"In the 21st century, there should not be almost 100 places reserved for individuals who were born into certain families, nor should there be seats effectively reserved only for men," the government argued.

"Reform is now long overdue and essential."