It’s party conference season in Britain, a chance for members to meet and talk through their successes and failures from the election campaign – and start talking strategy for the next.

Perhaps inevitably after it suffered such a crushing defeat and the resignation of its leader, the Conservative party conference in Birmingham risks taking on the air of a wake. Quite a contrast, then, with the Lib Dem bash down in Brighton, which, complete with jet skis and beach volleyball, was very much a celebratory affair.

Admittedly, Labour’s get-together in Liverpool, plagued as it was by newspaper stories about supposedly dodgy donations and the row over winter fuel allowances, wasn’t quite as upbeat as one might expect from a party that has just won a sizeable majority.

Whatever the outcome, many (though by no means all) members of all the parties worked hard to help deliver MPs to parliament. True, the evidence that campaigning by party members makes much of a difference to election results is hardly overwhelming.

But it can obviously make a difference in the closest of constituency contests. Examples in 2024 would surely include Hendon, won by Labour by just 15 votes, Basildon and Billericay, won by the Tories by 20, South Basildon and East Thurrock, won by Reform by 98, and even Ely and East Cambridgeshire, won by the Lib Dems by 495.

The party members project, run out of Queen Mary University of London and Sussex University, has been surveying party members about their activities after every election since 2015 and has just completed the 2024 exercise. And it appears that, following a decline in election campaigning in 2017 and 2019, there was a slight uptick overall this time round.

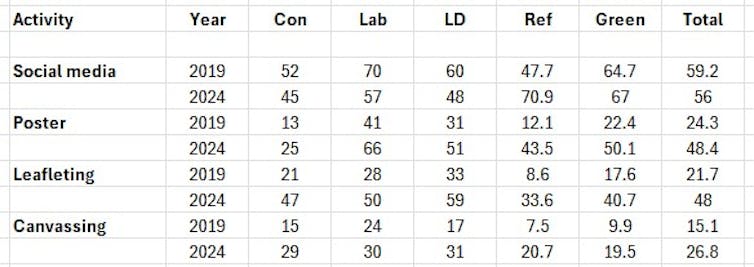

A simple way of looking at this is to note the proportion of respondents who told us they’d spent no time at all campaigning for their party (see Table 1). This rose considerably in 2017 and even more so in 2019 but dropped noticeably this year, suggesting the grassroots are getting a little more active, even if they’re still spending way less time campaigning for their parties than they were a decade ago.

Table 1: Percentage of party members saying they spent no time campaigning during the 2024 general election:

However, the uptick was due largely to the time put in by members of the smaller parties rather than by those belonging to the Conservatives or Labour – although it should be said that members almost certainly tend to overestimate the time they put in.

Indeed, worryingly for Keir Starmer, Labour members actually appear to have been no more active (and in some respects perhaps somewhat less active) than they were five years ago. This is possibly owing to the departure of many of those fired up by Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership in 2017 and 2019.

On the other hand, if we dig into the type of activities members got involved in, a slightly different picture emerges. Members of the smaller parties may be putting in the work, but they’re doing it from the comfort of their homes rather than pounding the pavements.

If we exclude the admittedly large number of party members who told us they either did nothing for their party or just hit “don’t know”, a whopping 71% of Reform members and 67% of Green members who were active said they spent time campaigning on social media in 2024. Just 45% of Conservative members who had done at least something for their party during the campaign said the same.

However, Reform and to some extent Green members too, were less likely than members of the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat parties to do some of what, in the jargon, is known as high-intensity activity – the stuff that involves direct contact with voters (or at least their letterboxes).

Table 2: What active party members got up to in the 2024 election campaign (percentages):

Interestingly, the members of the “old” parties appear to have done less on social media than they did in 2019. Instead they put their efforts into activities that, research suggests, do sometimes make a difference, such as leafleting. The Lib Dems (as ever) emerged as the champions when it came to this activity, with 59% of members who did something for the party during the election stuffing campaign literature through British households’ letterboxes. Whether it got read on its journey from front door to recycling bin, of course, is another matter.

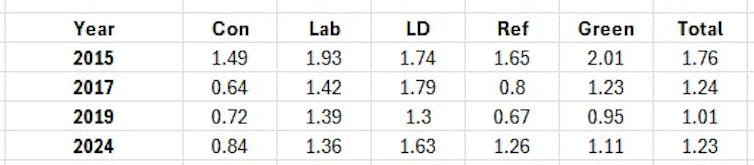

But what also comes through strongly is that, worryingly for whoever takes over as leader from Rishi Sunak, Conservative members seem to be lagging further and further behind their main rivals – Labour and (especially) the Lib Dems – on campaign activities overall (see Table 3).

Table 3: Average number of activities (out of a total of nine) done by all members of each party during the 2024 general election campaign:

Now, nobody would argue, of course, that this was the main reason the Conservatives lost the election so badly. Nor should anyone imagine that simply recruiting and enthusing more members – something each of the candidates vying to become Tory leader has vowed to do – will rapidly reverse the epic defeat the party suffered this summer. But it certainly wouldn’t do it any harm in the long term.

After all, the Tories almost certainly have a very long and very hard road ahead of them in opposition. Persuading more people to join the party, and encouraging as many of those who do join to get out “on the doorstep” (or even just to go online if that’s all they feel up to), might not make that road much shorter. But it might make it feel just that little bit easier.

The Party Membership Project received Talent and Stabilization funding from Research England, via QMUL, for this survey research.

Paul Webb has previously received funding from the ESRC to conduct research on political parties.

Stavroula Chrona does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.