The Bank of England has changed its mind about the prospects for the UK economy. Having been predicting a recession in 2023 as recently as February, its latest May report is expecting a soft landing from the bout of high inflation and a year of interest rate hikes.

One reason is that global demand for goods and services is expected to be higher. The central bank now expects weak GDP growth of 0.25% in 2023 compared to a predicted 0.5% contraction in the previous report, and thinks growth will be 0.75% in both 2024 and 2025. It said:

Growth over much of the forecast period will be materially stronger than in the February report. This reflects stronger global growth, lower energy prices, the fiscal support in the spring budget, and the possibility of lower precautionary saving by households than previously assumed in turn related to a lower risk of job loss …

This is quite a different picture to the one depicted by the IMF (International Monetary Fund) in April. The IMF said UK GDP would fall 0.3% in 2023 but then rebound to 1% in 2024.

Its reasons for being more pessimistic are that the UK was heavily exposed to the recent global shock in energy prices, its banks are vulnerable to the crisis engulfing the US, interest rates are high and the public finances are somewhat precarious.

Even the recent efforts by Chancellor Jeremy Hunt to revitalise the economy, such as encouraging business investment and simplifying international trade, were not met with enthusiasm by IMF economists. The chancellor was left vowing that the UK economy will “prove the IMF wrong”.

The difference between these two sets of forecasts is striking. The question then becomes, is the Bank of England too optimistic about the future UK economic outlook or is the IMF painting too gloomy a picture?

Understanding the difference

The IMF has been one of the most pessimistic forecasters about the UK economy of late. As the chancellor said during his spring budget, “our IMF growth forecasts have been upgraded by more than any other G7 country”. Indeed, even the IMF’s April forecast is a revision upwards from the 0.6% contraction for 2023 that it was fearing back in January, bringing it closer in line with the 0.2% contraction that the government’s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicted at the time of the budget.

This apparent lag in the IMF forecasts may be linked to how often it updates its economic models. The Bank of England and OBR do this routinely as new data becomes available, ensuring that the projections adapt more quickly to changes in the underlying economic signals. In forecasting, data revisions play an important role in updates. For instance, the OBR updated its assessment of the public finances in late April on the back of new data about the spending deficit.

In contrast, global institutions like the IMF and OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development) conduct their reassessments much less frequently (usually twice a year). This means that institutional forecasters have less chance to update their projections and that when they do so, they’re usually a few months behind the curve.

What next

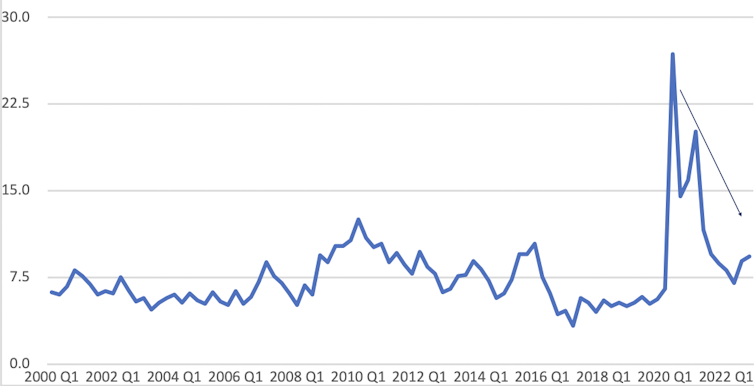

Be that as it may, is the Bank of England is likely to be right? On the prospect of increased household spending, the bank is seeing consumers dipping into their COVID savings because they’re feeling more secure in their jobs at a time when the redundancy rate has dipped sharply from pandemic levels.

Household savings ratio 2000-22

I would certainly agree that this will give a decent boost to the UK economy if the trend continues. The risk is that unemployment may start rising again and consumer confidence will tank. This would probably cause people to hold on to their savings and essentially shut down this growth channel.

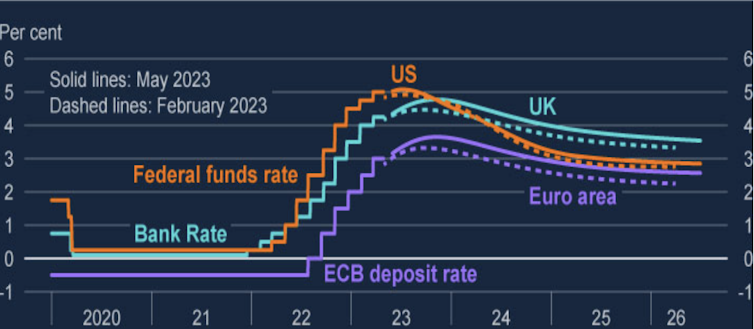

As for interest rates, the latest Bank of England report sees the base rate peaking at 4.75% in the final quarter of 2023 and then coming down to around 3.5% by 2026. With the base rate already now at 4.5%, this means the bank is signalling that the hiking cycle is almost over.

We know that households and firms base their spending decisions not only on current interest rates but also on this “forward guidance”. So an expectation of lower rates might indeed increase spending and investment, as well as having a positive effect on the housing market, which currently seems to be stabilising after a few months in decline. However, the latest bank forecast is also that interest rates will come down more slowly than before, so this might actually weaken spending and investment.

Interest rate projections (UK, US, eurozone)

Then there is inflation. The bank expects inflation to fall sharply this year and get back below the 2% target in 2024, which is good news. Nonetheless, the risks of higher inflation remains in the form of firms passing on past energy hikes to their customers via higher prices. There could well be more of this to come, so it could be that the bank is too optimistic here.

If so, interest rates will probably have to stay higher and the economy will have a harder time than the bank currently thinks. So while the bank is very likely a better judge of the UK economy than the IMF, there are still numerous reasons why it could be wrong on this occasion.

Luciano Rispoli does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.