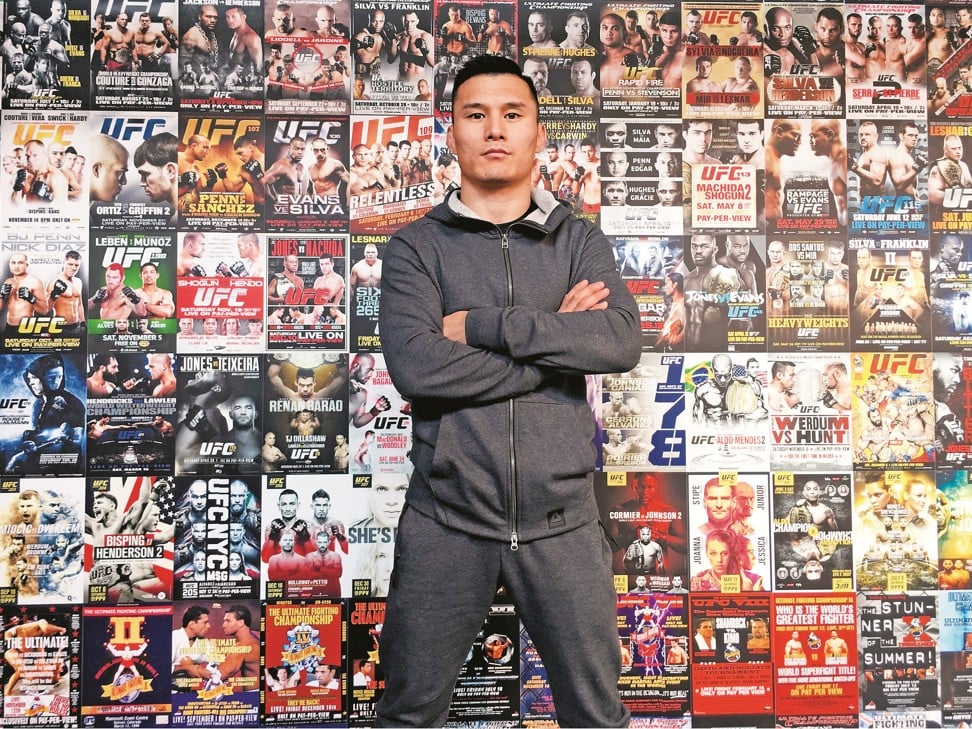

From the vast grasslands of China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region to the confined, sweaty space of a mixed martial arts arena, fighter Heili Alateng has come a long way.

In his first Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) bout held in Shenzhen, southern China, in August, the 27-year-old bantamweight beat Mongolian Batgerel Danaa by unanimous decision and pocketed US$70,000 – his biggest ever cash prize.

Alateng’s mixed martial arts (MMA) career began in Beijing in 2013. “I came from the Xilinguole grasslands,” he says. “Wrestling, riding and archery are the three competitive sports in the annual Naadam, a traditional festival in Mongolia. My dad was a wrestler who took part in it.”

Alateng took wrestling lessons in school and joined a team in Beijing after being spotted by a talent scout. It was in the capital that he began to watch MMA fights, and fell in love with the sport.

“I then left the wrestling team and joined an MMA gym in Beijing to practise. The UFC discovered me in 2017,” he says.

Alateng, nicknamed “the Mongolian Knight”, is one of a growing number of Chinese fighters to have burst onto the international MMA scene in the past few years.

The country got a huge boost in August when female fighter Zhang Weili became the world’s first Chinese – and Asian – UFC champion.

The fierce strawweight stunned enthusiasts with a technical knockout 42 seconds into the first round of a bout against Brazilian Jessica Andrade at the Universiade Sports Centre in Shenzhen.

Three fighters from China – Zhang, Song “Kung Fu Monkey” Yadong, and Li “The Leech” Jingliang – now rank among the top 20 contestants in the UFC, which held its first fight in China in 2017, in Shanghai.

The potential for Chinese fighters to become world champions had been predicted by UFC, the world’s biggest MMA promoter, which opened the UFC Performance Institute in Shanghai in June of this year.

The state-of-the-art, 8,600-square-metre (92,600 sq ft) facility is almost three times the size of the UFC’s original Las Vegas institute.

Dean Amasinger, director of MMA and head coach at the Shanghai facility, says China has more MMA fighters than any other nation in Asia.

“There are 500 global UFC fighters. Twenty-three of them come from Asia, not including Australia,” he explains, and 10 of them are from China.

A former MMA fighter from Britain who went by the nickname “Renegade”, Amasinger’s job is to help Chinese fighters advance into the UFC league.

“We built the Shanghai facility to accelerate the progression of Chinese fighters,” he says.

“Currently, the biggest market for the UFC is the US. But China has the potential to be the number one market in the world. We used to have offices in Singapore, but now all our Asian operations have been moved to Shanghai.”

Chinese fighters are disciplined and eager to learn, Amasinger adds.

“They are easy to work with as a group. They respond well to authority in terms of what we’re telling them to do. They are also very humble, unlike people elsewhere who might have a prima donna attitude once they reach a certain level of success. They [Chinese fighters] are appreciative of the UFC experience and grateful for our facilities.”

Amasinger says that although Chinese fighters largely measure up to their overseas peers, they need coaching to streamline their individual fighting skills into a comprehensive whole.

“Many people can wrestle, or strike, or do jiu-jitsu,” he says. “But the biggest challenge in MMA is putting those things together and making them seamless. The Chinese fighters do the individual martial arts very well, but they still lack slightly in integration. That’s what we’re trying to get them to do.”

The Shanghai academy takes in only Chinese fighters and currently has 26 athletes on its books, who train full-time and live in UFC-provided accommodation.

Alateng was its first trainee to graduate to the UFC division. He says that compared with other gyms, the facilities here help him recover better after vigorous training.

“I have to practise for five hours every day. I do sauna and cold water therapy. I also use the other facilities, like the underwater treadmill. The coaching system in the Shanghai academy is also something that cannot be found in a local gym. I train with experienced overseas fighters from Australia and the UK,” he says.

The UFC, which has held four events in China and plans to organise at least three events in the country next year, entered the Chinese market later than its competitors.

The Singapore-based One Championship, established in 2011, made its first big impact in 2015 with a tournament in Beijing. With offices in the capital and Shanghai, it has since held more than 10 China events and has more plans in the bag.

Amasinger also says that the UFC aims to build a pay-per-view market in China, like its US model. “With the time difference between China and the US, events held in China can still be popular in the US,” he says. “So an event held in China on Sunday morning can become a pay-per-view event on Saturday night in the US.”

Viewers in China currently watch fights on subscription services. All the major streaming platforms, including Tencent and Youkou, broadcast live MMA fights. In April, China’s answer to Netflix, iQiyi, launched exclusive broadcasts from Bellator, an American MMA promoter based in California and owned by media conglomerate Viacom.

We want to elevate Chinese MMA to a higher level and we want to find out who the best fighters in China are ... We see a big opportunity in helping to develop the Chinese market – Matthew Kwok of the Legend Fighting Championship

Over the past decade, local Chinese MMA promoters have blossomed, nurturing talented fighters who have gone on to join overseas leagues such as the UFC and One Championship. China’s original MMA promoter – the Art of War Fighting Championship – held its first fight in 2005 at Beijing Sport University.

The now-defunct outfit produced some of the best Chinese fighters to date, including Li Jingliang and Li’s mentor, Zhang Tiequan, who in 2010 was the first Chinese fighter to compete in a UFC competition.

At the peak of Zhang’s career, MMA was still regarded as an extreme fringe sport and appealed to few Chinese. In 2012, when he fought Japanese rival Issei Tamura in Zhang’s fifth UFC fight in Tokyo, he travelled solo with no entourage or sponsor.

His lone figure at the ropes contrasted sharply with that of Tamura. The Japanese fighter was surrounded by fans offering him drinks and mopping up his sweat. Zhang lost the fight.

Other local MMA promoters include Ranik Ultimate Fighting Federation (2011 to 2014), Kunlun Fight, developed by Beijing-based Kunsun Media, Chinese Kungfu (CKF) and Wulinfeng, run by Henan Satellite TV.

Former Hong Kong Olympic swimmer Matthew Kwok has also become involved in the MMA scene. In 2014, he bought Legend Fighting Championship, a Hong Kong-based MMA promoter founded in 2009 that attracted fighters from throughout the Asia-Pacific to compete for regional supremacy.

The last Legend event under its previous owners was held in 2013. After a five-year hiatus, Kwok and his partners relaunched the brand in 2018 with an event in Guangzhou. The next Legend event is scheduled for December 28 in Macau.

Kwok runs a production company in the US that broadcasts sports events including National Football League games and Legend tournaments. He has now narrowed Legend’s focus from the Asia-Pacific to the Greater China region.

“After the relaunch, we are focusing on Chinese athletes,” he adds. “Li Jingliang came from Legend. We want to elevate Chinese MMA to a higher level and we want to find out who the best fighters in China are. While there are a number of local MMA promoters in China, their events can’t be seen on overseas channels like Fox Sports. We see a big opportunity in helping to develop the Chinese market.”