For the last nine months, there's been a lot of back and forth between the U.S. and China regarding access to chipmaking and chip processing technologies. There've been many shots fired from each side, with each move denying access to either rare earth materials required to build semiconductors (this one leveraged by China) or imports of cutting-edge technology that might have military or intelligence applications, including AI (this part of the equation being leveraged by the U.S. and its allies).

Despite the number and length of tech and export restrictions levied against China, however, the actual effect of the ongoing trade war has often been questioned. But customs data just released by Beijing seems to point to effects aligned with the United States' expectations: China's year-over-year imports for chips and chipmaking equipment fell 22% and 23%, respectively.

"The controls appear to be making it harder and costlier for China to gain certain inputs," said Emily Benson, a senior fellow specializing in trade and technology at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank.

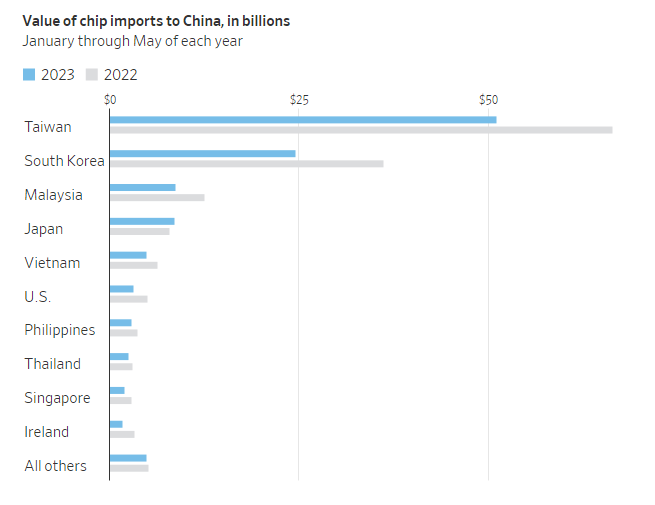

Looking at the numbers and the U.S.'s sixth-place position, it's clear that there's been a marked reduction (23% decline) in China's chip imports. But we also have to look at these numbers with a grain of salt, as it would be a mistake to assume complete causation between the restrictions and the lower US import number.

The US restrictions are primarily imposed by restricting exports from other countries to China, and with that perspective, it's important to note that Taiwan (and TSMC) have accounted for a significant reduction in China's chip import numbers (around 40% since the start of the year), followed by South Korea (home of Samsung and Hynix). Interestingly, Malaysia, Japan, and Vietnam follow with the most significant declines.

The U.S. appearing in sixth place is also interesting, despite the likelihood of most of its products trading at an above-average Average Selling Price (ASP) due to their likely "high-tech" status. But trying to gauge the graph's scale, it seems that even last year, the U.S. only accounted for around $6 billion of China's imports. That's a drop in the bucket for China's total expenditure, which saw Taiwan supplying about $70 billion over the same time frame.

Looking at the graph, it's clear that China has slowed chip imports across all of its top-ten providers. It's fair to assume that at least some of the slowdown shown in the graph doesn't stem from sanctions but from the softly dangerous state of the global economy, so it's possible that not all of that disparity stems from US-imposed sanctions.

The global semiconductor research, fabrication, and distribution system is a complex monster built out of many simultaneously-moving parts. It would take a supremely coordinated effort from several players to make the restrictions completely watertight, so some sanctioned goods will still flow, albeit more slowly. Furthermore, we must remember that China isn't just laying down in defeat as the world throws its punches: the country has been investing billions of dollars into education and high-tech research that it hopes will allow it to cushion import restrictions by replacing foreign tech with its own.

"Whether the controls remain successful or whether they inadvertently accelerate Chinese indigenization efforts" remains to be seen, added Emily Benson from CSIS.