It was the breadboard story that led me to believe James Lewis was most likely the Tylenol Killer.

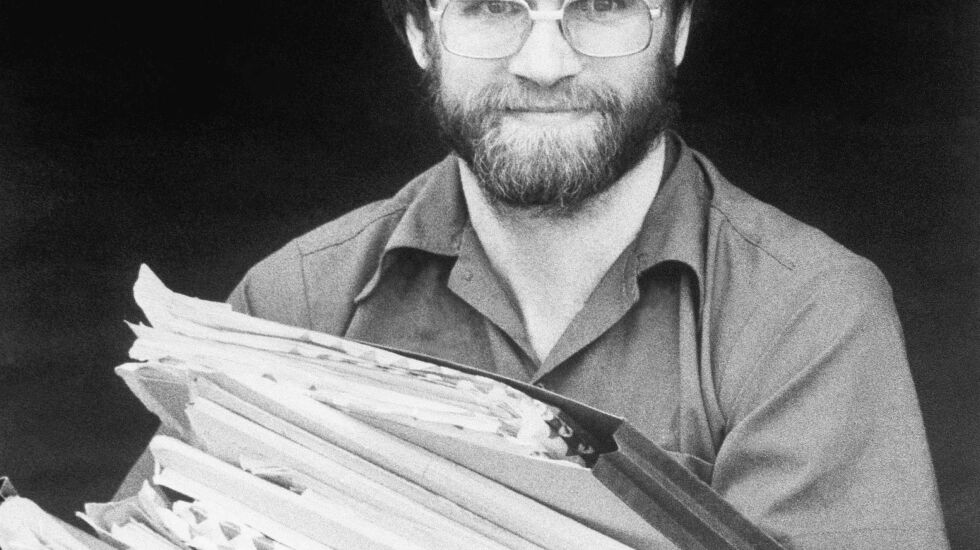

In the summer of 1987, as Chicago was coming up on the fifth anniversary of the Tylenol murders, I interviewed Lewis at the federal penitentiary in Danbury, Connecticut, curious as to what he might want to say, which turned out to be a lot and nothing.

But I felt a physical chill when, in the tone of a man who thinks he’s clever, Lewis offered to explain to me how any mope — though certainly not himself — could have safely and efficiently filled Tylenol capsules with deadly cyanide.

It was simply a matter of drilling holes in a breadboard, Lewis explained, and inserting half a Tylenol capsule shell into each hole. Then, he said, the mope — certainly not him — would brush the powdered cyanide across the board with a table knife, letting it fall into the capsules.

But you didn’t do it, James?

“No,” he said. With a smile.

Now Lewis is dead, and with his death a near-dead police investigation into the Tylenol murders grows even deader, and were it not for the continued pain of the families of the victims — who still deserve answers to this day — you have to wonder how much it matters anymore.

Maybe Lewis was the Tylenol killer, as many investigators believe, or maybe Roger Arnold was the killer, as other investigators believe. Arnold was a sad sack who worked on a grocery store loading dock until investigators briefly held and questioned him as a possible suspect.

Or maybe it was somebody else.

But the damage was done right then and there, in September of 1982, and it was permanent. We live with the fall-out even now. Soaked into our civic DNA is a diminished sense of trust and safety that began the day we learned we couldn’t even take a pill for a headache without having to think twice.

The effort to track down the Tylenol killer was intense and very public. Our whole city was on edge, and law enforcement at every level, from the state to the suburbs, wanted everybody to know they were working this one super hard.

Yet nothing ever came of it. Nothing.

Lewis went to prison for extortion, not murder. And Arnold, who died in 2008, went to prison for murder, but not for the Tylenol murders. Because Arnold had been questioned, his co-workers on the loading dock got to calling him the “Tylenol Kid.” This so infuriated Arnold that he stood outside a bar on Lincoln Avenue one night and shot dead the man he thought had dropped his name to the police.

We learned lessons as a nation, and certainly as a city, and I learned a couple of lessons as a reporter.

In the September of Tylenol, we were reminded horribly that we are only as safe as the strength of the so-called “social contract,” that unspoken yet fundamental assumption that we’re all in this together or we’re all lost. For all our laws and prisons. We trust that others won’t steer their car into our car, won’t push us off a cliff, won’t put poison in pills and sneak them onto the shelf at Jewel.

We learned, well before these current days of constant mass shootings, that we can’t assume the strength of the social contract. It can fray. It can die. We have to feed it, believe in it, from the bottom up.

As a fairly young reporter — I was an intern at the Sun-Times that summer — I learned to take a deeper breath when cops throw out names, first of one person of “interest” and then another. I wonder to this day whether I should have written one of the earliest stories about the emotionally volatile Roger Arnold, pulled together in a rush from notes I took while driving him up the Stevenson Expressway to his lawyer’s office. I wish I had not.

I also learned, as the former Chicago Reader media critic Michael Miner once observed, that people in deep emotional crisis — like the mother I interviewed of one of the Tylenol victims — will tell a reporter almost anything if you approach them right.

They are desperate to help anybody because they can’t do a thing for the person they lost. So if you, the reporter, softly say “can you help me?” they will help you, maybe even when they should not.

It’s a power to be engaged in respectfully.

The Tylenol killings left Chicago with an historic murder mystery that remains unsolved, though maybe the cops will get there still. But our sense of confidence in a civil society, where crazy, homicidal stuff doesn’t happen just for nothing, took a nightmare of a hit, and the hits have kept on coming.

On the Fourth of July, at least 18 people died in 17 mass shootings in our country.

The Tylenol killings and all those mass shootings are not unrelated.

Tom McNamee retired as Editorial Page editor in 2021 after four decades at the Sun-Times