Kevin Ireland attends two strange funerals

Ian Middleton was a lovely, brave man and there was such a lot that could have been made more of. During the war, by sheer chance, he had joined a Free Norwegian vessel in the merchant navy. He was a boy of fifteen when he first went to sea on convoy duty, and it was only in the 1990s that John Connor, of the New Zealand Society of Authors, had to pressure Ian into applying for and receiving his Norwegian war service medal. He had led an improvised, unusual life and it was only as he got older that he discovered a gift for writing — just as his eyesight was fading.

Like his brother, OE (Ted) Middleton, who was also a writer, Ian suffered from a progressive and incurable eye disease. In the 1950s his sight began to deteriorate significantly, though he was able for years, with the help of skilled subterfuges, to operate as an office machine salesman and mechanic, until he did finally become completely sightless. For a while he managed to live and work in Japan, and with fortitude he continued to write and publish until his death. His early novel, Pet Shop, is one of those simple yet beautifully angled and ‘voiced’ works that marks it out as an offbeat little gem. A strange and stunning book that breathes life into our past.

His funeral was somehow held together by the bright spirit of Naomi, Ian’s young daughter. A hall and hearse had been organised, but nothing apart from a microphone had been prepared to commemorate the important strands of his life — though quite a lot was made of the coincidence that the day of his funeral was also his birthday.

As the funeral ended, Graeme Lay and I thought we’d slip away and avoid the probably equally disorganised get-together that was to follow, so we decided to shift towards a door while the going was good. We escaped just before the coffin was carried out to the waiting hearse, but as we disappeared, we could hear a very familiar song drifting from the distance. What we picked up faintly, but couldn’t witness by sight, remains up there with the most outlandish moments of commemoration I’ve ever known anywhere and at any time — and I still imagine Ian nearly shaking his coffin to bits with laughter, for (as I discovered later) the song had not been prearranged. Without prompting, the whole gathering, as if with one voice, suddenly broke into:

Happy birthday to you,

Happy birthday to you,

Happy birthday, dear Ian,

Happy birthday to you.

*

Ian’s extraordinary send-off was matched by the well-kept subterfuge behind the equally surreal funeral of another friend. However, I have to say first that this ceremony was a controlled and orderly affair. People came from long distances to attend and to deliver valedictory speeches over the coffin. Pleasant music was played and the solemn rituals and tributes were conducted in a structured way. At the end, the coffin was picked up by young pallbearers and carried out respectfully, but with what I thought to be surprising ease, to the hearse. Then slowly away it went.

It was only over a cup of tea and a sandwich afterwards that my suspicions found an answer. I was let in to the hush-hush secret that the body had had to be cremated swiftly a couple of days earlier and it had been converted into a small box of ashes, which had only just been collected and taken home. However, a family decision had been made on the day before the funeral that the ceremony should still take place, since it had been advertised as such and people would not expect to find that they’d come to a memorial service. Many of them would be making a long journey from the far north to be there and they’d wish to farewell the last remains of a friend.

"But," I said, "the coffin looked very light. Something was there. So what was in it? And were the undertakers in on the deception?"

It turned out that the arrangement with the firm was a full-scale conspiracy and I suspect it to be one that had been perfected by practice — after all, hadn’t the undertakers already neatly adapted part of their services by managing to conduct an earlier, efficient and private, inner-family cremation? The truth was that, late on the previous day they had delivered a nice, clean, empty coffin to the house, and for the ‘funeral’ they then returned knowingly on the day notified, to pick it up and deliver it to the hall where the service was held. They had performed their part of the proceedings with all the usual stony-faced flourishes, in their dignified undertakers’ suits, then they had taken the coffin away, not to the crematorium, but to their own premises around the corner where they had emptied it and placed it back on sale.

I had to ask again, "But what was inside the coffin that we had just paid our last respects to — what was it exactly that the dignified speeches had been directed at — and what was underneath the lid that old friends had slapped as they gave whatever-it-was a final farewell?"

The answer was astonishing. When the family had considered what would be the best possible dead-weight (so to speak), the obvious answer was to use a pile of books. But the funeral directors had objected (again, I suspect, through occasional and very discreet practice). Books would involve the nuisance of having to store them so they could be collected again, plus there was the risk of loss, and they suggested the best thing would be magazines, which would make an equally stable thingummy for the pallbearers to carry without strain. Later on, the magazines could be disposed of by simply biffing them all away in the council-collected recycled rubbish. It so happened that, when they looked around the bereaved house, there were lots of issues of a popular magazine ready for disposal.

I can claim to have attended what few other mourners there will ever know was the solemn funeral of a pile of printed paper. They had just paid their last respects to a corpse composed entirely of about five dozen copies of Woman’s Day.

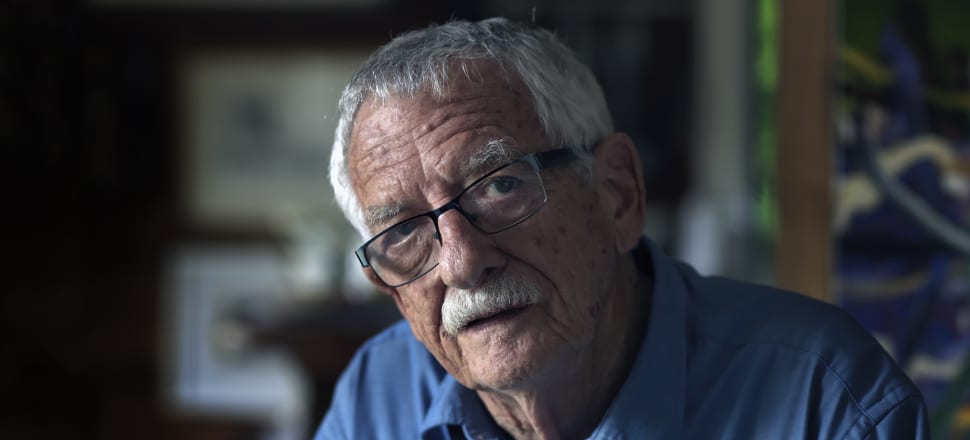

Taken with kind permission from the newly published memoir A Month At The Back of my Brain by Kevin Ireland (Quentin Wilson Publishing, $40), available at bookstores nationwide. ReadingRoom is devoting all week to the author's third memoir. Yesterday, his wife Janet Wilson wrote a portrait of her husband; tomorrow, a tale of love at first sight.