The spat between Nigel Farage, the leader of the Reform party, and Rupert Lowe, the MP for Great Yarmouth, burst into the open when Lowe was suspended from the party. The allegation was that he had threatened violence to the party leadership, which he denies. The matter is currently being investigated by the police.

The row does not appear to have affected support for Reform in the polls. A YouGov poll completed on March 10, after Lowe’s suspension, shows Reform on 23% in vote intentions, compared with 24% for Labour and 22% for the Conservatives. It is still a three-party race at the top of British party politics.

In the 2024 general election a good deal of Reform’s support came from protest voters. These are voters who dislike all the mainstream parties and so see a vote for the party as a way of choosing “none of the above”. They are not attached to any party and can easily switch support when circumstances change. So why has support for the party not been affected by this row?

Protest politics and support for Reform

The answer to this question is that while Reform attracted a lot of discontented protest voters in the election, it has since acquired a more stable niche in British party politics. It is primarily a party of English nationalism, equivalent to the SNP in Scotland and Plaid Cymru in Wales. These three parties differ greatly in outlook and politics, but they occupy a similar place in the public’s minds.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday.

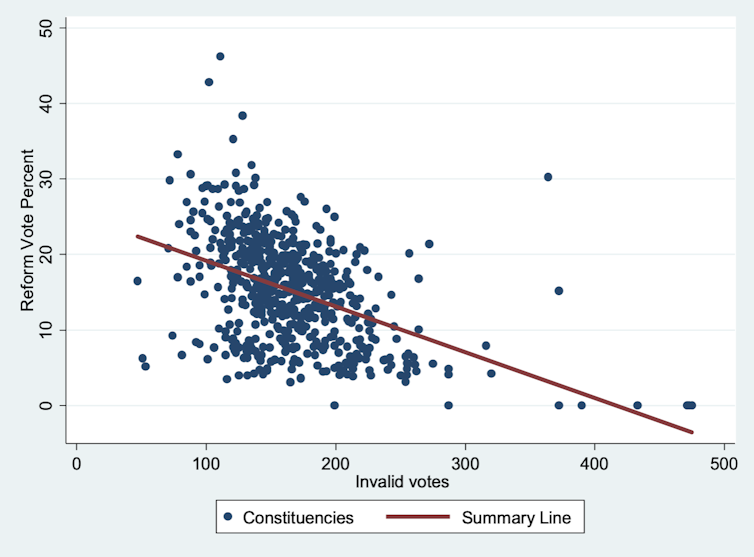

To examine Reform’s support from protest voters we can look at the relationship between spoilt ballots in the 2024 general election and support for the party in the 632 constituencies in England, Scotland and Wales. Normally, observers of British elections pay little attention to spoilt ballots (or “invalid votes” as they are described in official statistics). However, it turns out that they played an important role in the 2024 election which has a bearing on support for Reform.

Research shows that voters who spoil their ballots can be classified into two categories: those who simply make a mistake when filling in the ballot and those who are protesting about the current system.

Mistakes are easy to make in countries with complex electoral systems. However, in Britain, the first-past-the-post system in which everyone has just one vote, ensures that this is not a significant factor because ballot papers are so simple. The bulk of spoilt ballots are protests of various kinds, taking the form of blank ballots, write-in candidates, or abusive messages about parties and candidates.

This is illustrated in the Lancashire seat of Chorley, which is held by the speaker of the House of Commons, Lindsay Hoyle. By tradition none of the major parties challenge the Speaker by campaigning in his constituency. In the election there were no less than 1,198 spoilt ballots in his constituency. It is fairly clear that these were a result of some voters feeling disenfranchised by the absence of their preferred party on the ballot paper.

The relationship between the Reform vote share and the number of spoilt ballots in constituencies in the 2024 election

There is a strong negative relationship (a correlation of -0.46) between the share of a constituency vote that went to Reform in 2024 and the number of ballots spoiled in that constituency. Where people were voting Reform, in other words, fewer people were spoiling their ballots. The implication is that the party picked up votes from people who would normally spoil their ballots or would not have voted at all if Reform had not stood in their constituency. These are the protest voters.

Identity politics and support for Reform

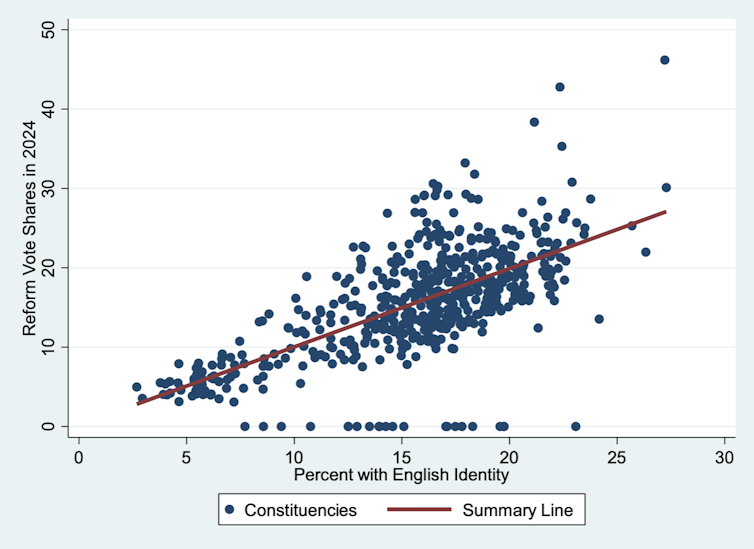

Not all support for Reform came from protest voters, however. The chart below compares the percentage of Reform voters with those who identified as English in the 2021 census in England. There is a strong relationship between the two measures (a correlation of 0.66). The more English identifiers there are in a constituency, the greater support for Reform. In effect, Reform has become an English national party.

The relationship between Reform voting and English identity in 2024

National identities can change over time, but the process of change is slow. There has been a growth in “Englishness” at the expense of “Britishness” over time and this is undoubtedly reinforcing support for Reform.

It means the party has a relatively solid base of supporters to rely on in future elections. While the row between the party’s leader and one of his MPs could play out in any number of different directions at this early stage, it would be wrong to suggest that Reform isn’t thinking big picture and long term.

Farage has clearly learnt from his past and will not let his current party disintegrate into chaos like UKIP or the Brexit party before it.

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.