Few people in recent times have created as much controversy as Donald Trump.

A year after his utterances got him banned from Twitter, Facebook and YouTube, his new enterprise Truth Social has made its debut on Apple’s App Store.

The platform, which is available as an app and website, was made available to download on the US Apple App Store yesterday, and has so far topped the download charts.

It will also be “coming soon” to the Google Play Store and other countries.

The timing of Truth Social’s debut on the symbolic US Presidents’ Day is certainly no coincidence. Is it, at the end of the day, another tool in Trump’s political arsenal?

Let’s just say Trump is likely keeping his options open.

Already hacked?

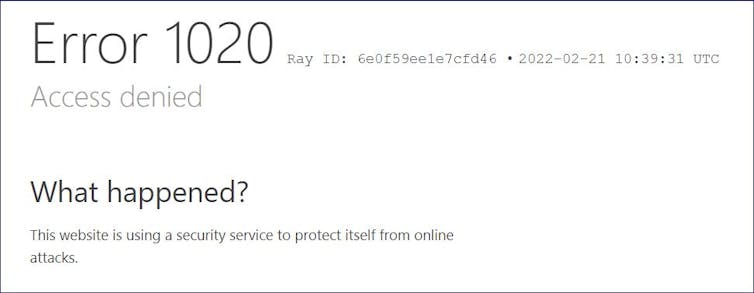

The Truth Social website has reportedly already been the target of hackers.

It seems some users who managed to get early access also secured user handles including “donaldtrump” and “mikepence”.

Tweet from @MikaelThalen

The site is offline at the time of writing this article, presumably while its cyber-security capabilities are upgraded.

It may be the site came under a sustained attack, or developers realised the need to thoroughly debug it before it goes live.

Data privacy

Truth Social’s developer, the Trump Media & Technology Group (or T Media Tech LLC), said the platform will routinely collect data about users’ browsing history, contact information (including their phone number) and any pictures or videos they post.

Importantly, this information will be linked to the user’s identity.

The platform will also gather “non-identifiable” data on how the user interacts with the application – supposedly to analyse usage patterns and personalise the user’s experience.

However, while these data are described as not being linked to a user’s identity, they nonetheless include the user’s email address and ID. This suggests they are, in fact, personally identifiable.

Potential implications of data collection

Having such richly textured information puts Truth Social in a position not only to learn about users’ opinions and behaviours, but also to target them with personalised political messaging.

The legalities of this practice would have been carefully vetted to be on the right side of the law (morally questionable as it may be). And the technology for it already exists.

It was used in the now-infamous Cambridge Analytica scandal which, as evidence suggests, could have aided Trump’s victory in the 2016 US presidential elections.

Big data analytics is advancing fast, made possible by ever-smarter algorithms, larger datasets and more powerful computers. It’s a game changer in the high-stakes world of politics.

It’s also no accident Truth Social’s user interface closely resembles that of Twitter: The platform used to greatest effect by Trump.

In a 2019 interview, Twitter co-founder Evan Williams described Trump as a “master of the platform”.

It could be argued his 57,000 tweets helped in no small way to make him the 45th President of the United States.

Will it be a far-right platform?

In the case of Truth Social, most of the opinions and ideas expressed will likely fall within the right of the political spectrum – everything from hardcore alt-right ideologies, to those slightly right of centre.

However, as the platform is reliant on Apple and Google distributing it on their app stores, it’s unlikely the Truth Social platform can afford to become a mouthpiece for the far right, as Gab has become.

If it is to survive, it must avoid the fate of Parler.

This hard-right Twitter clone was delisted by Apple and Google for hosting comments that incited violence during the pro-Trump riots at the US Capitol in January 2021.

It remains to be seen whether Devin Nunes, who heads up T Media Tech LLC, can avoid the platform becoming stridently right wing and being delisted.

Success will depend on Truth Social attracting a spectrum of political views from a substantial number of users.

This is something previous Twitter alternatives Parler, Gab and Gettr all failed to do.

Only time will tell whether Truth Social can avoid the mistakes made by other similar platforms.

But it does appear to be trying to distance itself from being perceived as hard right.

It has adopted a so-called “big tent” approach. To quote from the app store listing:

Think of a giant outdoor event tent at your best friend’s wedding. Who’s there? The combination of multiple families from all over the United States, and the world. Uncle Jim from Atlanta is a proud libertarian. Aunt Kellie from Texas is a staunch conservative. Your cousin John from California is a die-hard liberal … Although we don’t always agree with each other, we welcome these varied opinions and the robust conversation they bring.

Tweet from @RonFilipkowski

How Trump controlled the narrative

Robert Reich, former Secretary of Labour in the Clinton administration, outlines seven ways unscrupulous politicians exercise control over the media.

These include berating and blacklisting dissenting media and raising a lynch-mob mentality. Opponents are demonised, sometimes with the added threat of legal action.

Also in the playbook is the exclusion of critics from interviews and comments.

And last but not least is the exclusion of news outlets altogether, by using platforms such as Twitter to communicate directly with the public.

Before he was banned, Trump used Twitter to divert attention away from issues that could harm him.

And research suggests diversionary tweets can be used to suppress coverage of certain issues, allowing the tweeter in question to exercise control of the narrative.

For example, heightened media coverage of the Mueller investigation was countered by multiple tweets from Trump about unrelated issues. It was observed this was followed by reduced coverage of the Mueller investigation.

All of this adds up to the distinct possibility that Trump has already begun campaigning for election in 2024.

Instead of settling into comfortable retirement following his defeat in 2020, he has stayed in the limelight – behaving more like a candidate in waiting.![]()

David Tuffley, senior lecturer in Applied Ethics & CyberSecurity, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.