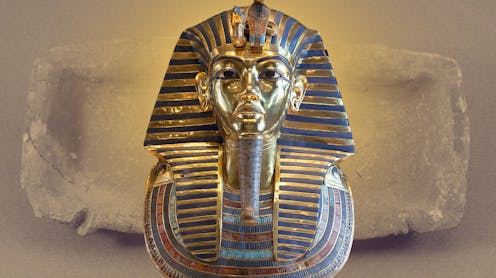

More than 100 years after the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings, new interpretations of the burial are still emerging. A recent article published in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology proposes that a set of seemingly plain, functional objects are in fact a key part of the complex rituals which would ensure the transformation and regeneration of the young king in the afterlife.

Tutankhamun inherited a throne tainted by the shifts in religious and political practices implemented by his father, Akhenaten. His reign had been hallmarked by the move from the capital city of Thebes to a new city, Akhetaten (“the horizon of the Aten”).

Under Akhenaten, the solar deity Aten was elevated above all others, including the principal state god Amun. This resulted in the king being the sole high priest and beneficiary (along with his family) of the Aten. The resulting disconnection between state and religion severely reduced the power and influence of priests and members of the royal court. But on Akhenaten’s death, these were restored by his son.

Tutankhamun was named Tutankh-aten (“the living image of Aten”) at birth, but took the name of Amun back when Thebes was restored as the capital city of Egypt after his accession. This time (known as the Amarna period after the modern name of Akhenaten’s city) and its changes mean that it is more challenging to understand matters such as burial practices, religious rites and so on because it was not necessarily a “typical” time.

Therefore, while we have learned much about funerary practices from Tutankhamun’s tomb, there are objects which are still being reinterpreted.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The artefacts in focus are a set of four clay trays, approximately 7.5 x 4.0 x 1.2cm, plain in design and apparently quite utilitarian.

This type of artefact is known from other funerary contexts including elsewhere in the Valley of the Kings. They have been described in various ways as mud trays, earthen dishes or troughs. The lack of consistency in terminology and suggestions on function illustrate the difficulty in understanding their precise role in the tomb.

Along with the clay trays are a set of wooden staves, just over a metre long, with a slight angle, and covered with gesso (a white pigment and binder mixture) and gold. In spite of the difference in materials, they were assumed by the man who uncovered the tomb, Howard Carter, to be directly associated with the trays. He believed they were probably intended as bases for the staffs to stand upright.

However, it is clear that they have an even greater function to fulfil as, contextually, everything in the tomb has symbolism and meaning, even down to the wooden boxes for preserved meats, which were intended to sustain Tutankhamun in the afterlife.

The care with which the trays and staff were laid out on matting indicates that they were important for the king’s burial. We might expect a royal burial to be filled with only the finest objects, made of the most valuable materials by elite craftsmen, with the association of materials such as gold with royalty and divinity. The richness of the rest of Tutankhamun’s burial for the most part fulfils this expectation. But, nevertheless, the ordinariness of the clay trays in the light of such riches confirms rather than refutes their significance.

The restoration of order

Following the royal court’s move back to Thebes in the wake of Akhenaten’s death, the restoration of Amun and the other gods was set in motion. The cult centre of Amun at the Temple of Karnak regained its status. The name of Akhenaten and his imagery, along with that of the sun disk, were subjected to a campaign of removal.

Tutankhamun erected the so-called Restoration Stela with titles and epithets invoking the traditional gods, and statements on “having repaired what was ruined … having repelled disorder”. The upheaval of the Amarna Period was reversed.

Discussions in academia on the dismantling of Akhenaten’s regime have tended to focus on issues such as name changes and the destruction of his upstart city. But ancient Egyptian religion had countless centuries of recorded tradition and observance, so profound demonstrations of loyalty to the traditional gods were needed.

The mud trays are now thought to be part of a wider funerary ritual, which both invoked the god Osiris and permitted the transfiguration of Tutankhamun. As king, he was thought to be the embodiment of the god Horus in life, and to become Osiris in death – rejuvenated and resurrected.

Osiris is usually shown as a mummified king, with green or black skin to represent the fertility of the land and the new life which comes from it. It is not a coincidence that the trays are made of mud.

Other aspects of the placement of the trays within the tomb such as specific placement and orientation (including particular symbols in the decoration of the tomb) indicate that the trays had a specific role to play. This may have been as an offering tray for Nile water, once more underlining the role of the river in creating life.

Tutankhamun and his treasures are so familiar today that it is possible to overlook, or even forget, the fact that once the doors were sealed after his funeral they were meant to never be seen again. Some of his grave goods – particularly those made from gold – have outshone others. However, the ordinariness of the trays among all the riches suggests that they are crucial components of his burial. They confirm Tutankhamun as both renewed in death through Osiris, and the king who restored order to Egypt.

Claire Isabella Gilmour does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.