Ancient Egypt’s most iconic treasure - the great golden face mask of the pharaoh Tutankhamun - was a second-hand family hand-me-down.

New research by the British Egyptologist, Nicholas Reeves, has revealed that it was originally made for a female pharaoh, probably the famously beautiful ancient Egyptian queen, normally known to the public today as Nefertiti.

The discovery sheds fascinating additional light on some of ancient Egypt’s most important but least well understood historical events – a religious revolution and counter-revolution which convulsed much of Egyptian society some 3350 years ago.

The episode has broad historical importance because it was arguably the very first attempt anywhere in the world to establish a monotheistic religious system. After just a few years, it failed – but perhaps significantly the Jewish Egyptian-associated prophet Moses and the Exodus are traditionally dated to a broadly similar era.

Nefertiti (translated as ‘the Beautiful Woman Has Arrived’) – the newly-revealed probably original ‘owner’ of King Tutankhamun’s famous golden death mask – was the wife of the monotheistic revolution’s leader, the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten (‘the Incarnation of the Disk of the Sun’). But she was also probably the co-architect of that short-lived ancient religious reformation – the top-down imposition of the worship of the disk (or ‘Aten’) of the sun, probably symbolising the essence, energy and power of the Sun God.

The evidence that Dr Reeves has found, suggesting that Tutankhamun's large, elaborate gold death mask was (apart from its personalized facial features) made for his mother (or possibly step-mother), Nefertiti, has come from a detailed re-examination of an inscription on the artefact assigning it to Tutankhamun. Very careful examination of the hieroglyphic text shows that the king’s names were actually inscribed over an earlier individual’s names which appear to have given the full official nomenclature used by Nefertiti after she had become co-pharaoh of Egypt – namely Ankhkheperure-Meryt-Neferkheperure Neferneferuaten (literally meaning ‘Living Manifestation of the Sun God, Beloved of Akhenaten, Beauty of Beauties of the Disk of the Sun’).

Interestingly, the second-hand gold mask completes a wider picture in which many of the major other treasures in Tutankhamun’s tomb (including his ‘middle’ coffin, miniature gold coffins for his internal organs, a gold breast ornament, some of the gold bands which adorned Tut’s mummified body and a gilded statuette) had all been made initially for other ancient Egyptian royals.

Thanks to Dr. Reeves research, Tutankhamun’s golden death mask has become part and parcel of one of Egypt’s greatest unsolved mysteries – where was Queen Nefertiti buried?

Despite more than a century of searching, her tomb has never been found.

However, earlier this year, Dr. Reeves threw the Egyptological world into some excitement by suggesting that there might be as yet undiscovered secret chambers within Tutankhamun’s tomb complex. He even raised the possibility that one could be Nefertiti’s lost tomb.

Three days ago, the Egyptian government therefore started carrying out a detailed geo-physical survey of the wall of Tutankhamun tomb – and have so far found several anomalies which they suspect may represent a hidden chamber.

Many Egyptologists suspect that Nefertiti’s lost tomb may be lurking under a mountain immediately opposite Tutankhamun’s tomb - so the newly detected probable additional chamber in Tutankhamun's tomb complex could well contain previously unsuspected additional King Tut treasures. But Dr. Reeves’ discovery of the hidden inscription on Tutkhamun’s golden mask itself is raising other questions.

Why was Nefertiti ‘robbed’ of her mask – and, when – and why was it given to her son, Tutankhamun. The answer probably lies in the difficult political situation that occurred during the collapse of the monotheistic experiment.

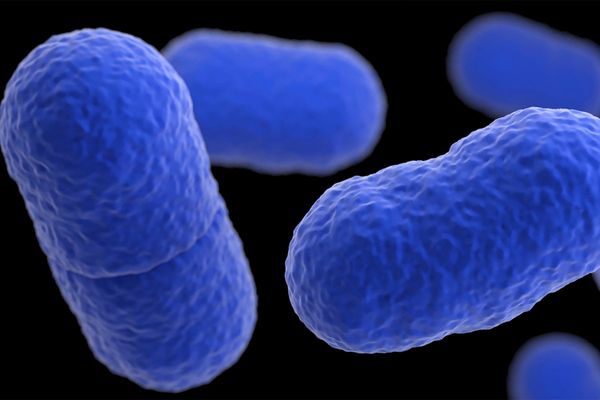

A decade after Akhenaten and Nefertiti had launched their religious revolution, some evidence suggests that Egypt may have been hit by a terrible epidemic. Desperate to ensure the continuation of his new monotheistic religion, and perhaps fearful of death, Akhenaten decided to appoint his queen, Nefertiti, as co-ruler. He did so just in the nick of time – for within a few months he did indeed die. His young eight year old son, Tutankhamun (at that stage called Tutankhaten), became pharaoh and Nefertiti (now only using her new longer pharaonic name) continued as co-ruler with him, says a leading historian of the period, Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol, author of two major books on the era – Amarna Sunrise and Amarna Sunset.

For three years Nefertiti seems to have tried to find a middle way between the old polytheistic system and the new monotheistic one. But then she too died. Nefertiti had made elaborate preparations for her own death and had expected to be buried as a full pharaoh of Egypt (complete with her pharaonic gold death mask).

But, after her death, two religiously traditional generals effectively seized power, using Nefertiti’s son Tutankhamun as a puppet pharaoh. They appear to have been determined to abandon Nefertiti’s policy of religious compromise and to return to full traditional polytheism.

Dr. Reeves discovery, that Tutankhamun golden death mask had originally been made for Nefertiti, is powerful additional evidence suggesting that after her death she was deliberately politically downgraded.

“This discovery re-enforces the view that, after her death, she was deprived of her status as a pharaoh and presumably buried merely as a queen,” said Dr Dodson.

The new evidence suggests that her death mask was therefore never used in her funeral or in her tomb – but was instead put in storage and eventually recycled for Tutankhamun.

King Tut’s golden mask – currently thought of as a mainly art-historical object – is now therefore likely to also become a symbol of the world’s first known major ideological struggle between monotheism and polytheism.