Old Christmas cards sit on the closed lid of a baby grand piano that Fats Waller once played. It’s not hard to imagine the comic entertainer’s eyebrows dancing as he tickles the keys.

A few feet away, a cluster of dusty music awards. And on the walls, a who’s who of Chicago jazz greats. It all feels like a shrine to a bygone era.

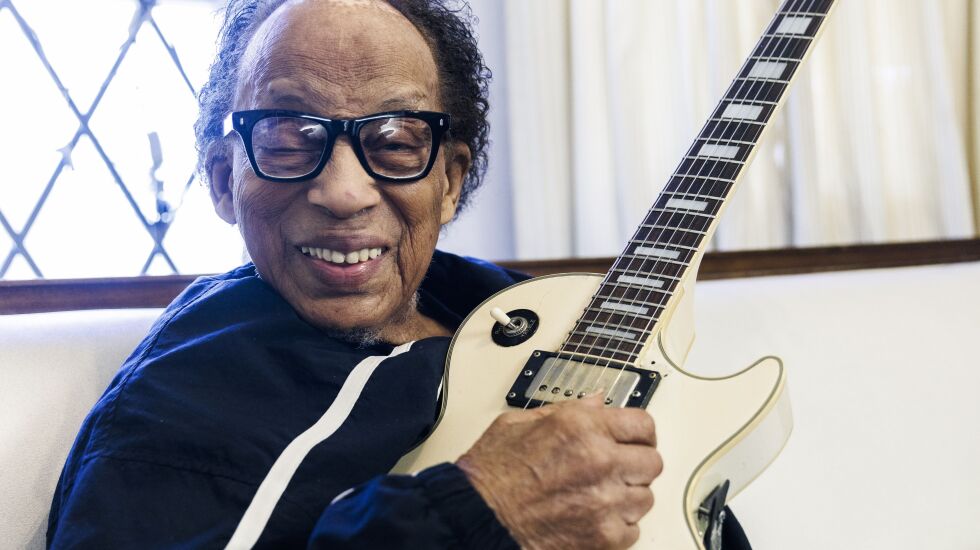

But then the stairs to this two-story South Side home begin to creak, and a man with fly-away hair and wearing a black warm-up suit hobbles down. He greets his guests with a wide grin and fist bumps.

It’s George Freeman, who played alongside many of America’s jazz and rhythm-and-blues greats, including Charlie Parker and vocalists Jackie Wilson and Billie Holiday. Freeman, about to turn 96, is still playing the jazz guitar — and finally getting the recognition his admirers say he deserves.

He plops down on his sofa and soon, eight decades-plus of a life in music begin to spill out.

“I would slip out of the house because I had to hear me some T-Bone Walker,” Freeman says of some of his earliest musical experiences growing up on the South Side. “He could sing the blues — pretty blues. He wasn’t gut-bucket blues. I watched him put that guitar behind his neck, and the women were going crazy.”

Freeman plans to celebrate his birthday with two live shows, April 7-8 at the Green Mill, with his band of the last 10 years. He’s set to release a new album, “The Good Life” (HighNote Records), recorded in 2022 in June.

He has thoughts about the next one.

“I would love to make a record one day with nothing but violin players. I love a ballad,” Freeman muses.

Music saturated Freeman’s childhood. His mother sang gospel; so did his grandmother. His father, a cop, played the piano that now sits in Freeman’s living room. Freeman’s better-known older brother, the legendary Von Freeman, would make a career of playing the saxophone.

In the late 1930s, Freeman’s dad, George Sr., would come home after a swing shift and crank up the family’s “Majestic” radio, its bass speaker booming the big band sounds of Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman, among others.

“I was waiting for him to come home; I wanted to hear that music,” Freeman says.

Musicians poured into the Freeman house, including Waller, whom Freeman’s father met while working the police beat outside the famous South Side jazz joint, The Grand Terrace.

T-Bone Walker and Charlie Christian, a Black electric guitar pioneer, drew Freeman to the six-stringed instrument.

Best known for playing the fast-paced and melodically complex bebop style of jazz, Freeman wanted the guitar to have the spotlight — not just as part of a rhythm section.

And he wanted his guitar to occasionally have the throaty bleat of a tenor sax player.

“They fascinated me, hitting the low note, and feet dancing up and down!” Freeman says.

He started in his teens playing in a local swing band, then later fronted his own band, playing gigs at the Pershing Hotel at 64th and Cottage Grove in the mid to late 1940s.

He played in New York, Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia.

“Charlie Parker completely fell in love with me,” Freeman says. “He wouldn’t go onto the bandstand without me. He’d say, ‘Where’s George?’”

Holiday was less flattering.

Freeman was accompanying her at the Regal Theater, where Ellington, Basie and Louis Armstrong had all played. At some point during the show, tears trickled down Freeman’s face.

“I’d never heard anything so beautiful,” Freeman says.

At the end of the song, Holiday glared at him and said, “What the hell are you crying about, fool?,” Freeman recalls.

Freeman spent the early 1970s touring with Gene Ammons, the Chicago tenor sax great. In 1971, Freeman’s name appeared on the cover of DownBeat magazine, a distinction that could have propelled him to national fame and a recording career with a major label, but that didn’t happen. Freeman’s guitar solo meanderings were too jarring, too unorthodox, some have suggested.

Freeman calls it “going outside,” or deliberately playing notes that clash with a tune’s key signature.

“If you listen to John Coltrane from his later period, he would use sounds of the saxophone to really develop the most tense aspects of the solo, and George is doing the same thing,” says Mike Allemana, a fellow jazz guitarist who plays with Freeman and has known him since 1991.

But now at an age when most musicians have long since retired, Freeman has a record coming out later this year on the New York label, HighNote. He gets regular invitations to perform.

There’s an admiration for his longevity and what he’s witnessed, but it’s more than that.

“He is extremely skilled at creating melodies that touch people,” says Allemana. “And he has that deep blues feeling that’s hard to master.”

During a recent visit to his Grand Crossings home, Freeman retrieves one of his guitars from a back room and plugs it into an amp. He sits when he plays now, and his fingers can no longer hold a slender pick; he uses a kitchen cabinet door knob to strum.

But his fingers still flutter and glide, like those of a musician half his age. A sound — half grunt, half giggle — escapes his lips when he hits a wrong note.

When he gets it right, just the way he wants it, he closes his eyes, nods and a smile warms his face.