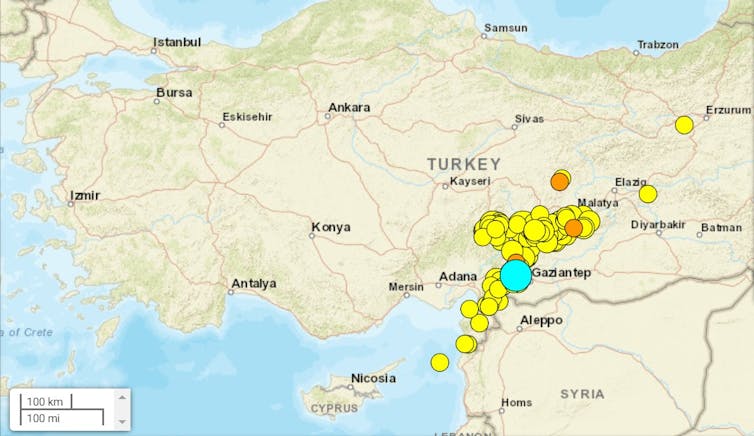

The magnitude-7.8 earthquake near Gaziantep that struck southeastern Turkey and neighbouring Syria on February 6, and the large aftershocks that followed, destroyed thousands of buildings and claimed tens of thousands of lives.

In response to criticism of the efforts to rescue buried survivors, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan reportedly said that it was “impossible to prepare for the scale of the disaster”. But is he right?

I don’t think so, and I will explain why.

It’s true that it’s hard to predict when and where an earthquake can happen. Days ahead, there are occasionally warning signs of a major earthquake such as inexplicable night-time glows in the sky or unusual animal behaviour. But these signals are untrustworthy, and poorly understood.

In Japan and California, there are warning systems that can give a few tens of seconds warning, setting traffic lights to red and bringing trains to a halt – but obviously not long enough for an evacuation of any kind.

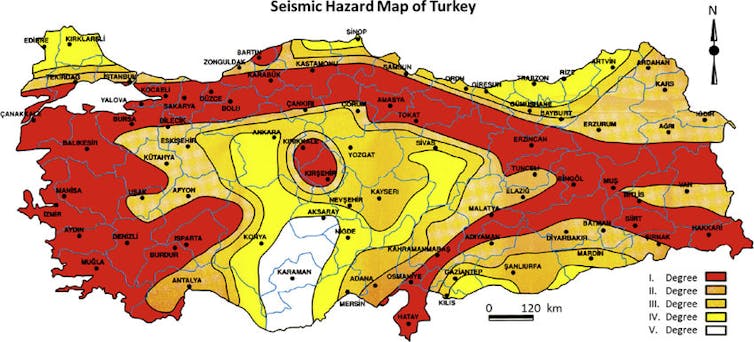

The Turkish government is well aware the country sits on active fault zones in the Earth’s crust, with a long record of earthquake activity. Yet it allowed builders to flout earthquake resilience construction regulations.

And seismologists are good at producing earthquake hazard maps, like one of the Turkish government’s own maps shown here:

Earthquake preparedness

Even supposing there was a reliable system that would give, say, one day or one month’s advanced warning of a big earthquake, how should it be used?

If it was up to you, would you try to move millions of people out of the area likely to affected? Would they be willing to go? Where would they live and work afterwards if they came back to find their homes destroyed?

The best way to prepare for an earthquake disaster, and what Erdoğan had it within his power to do, is to build homes and infrastructure using earthquake-resilience techniques. That way, people are not killed during the earthquake and they still have their homes afterwards.

There are many ways in which buildings can be designed and built to withstand earthquakes, so that they don’t collapse. In an area at risk of large earthquakes, a multistorey building should be designed so that when the ground starts to shake, its outer walls on either side sway in unison in the same direction as each other.

If, on the contrary, opposite walls are free to sway away from each other, the intervening floors become momentarily unsupported, allowing upper floors to pancake down on to lower floors. This happened to deadly effect in Turkey.

Builders can prevent this by structurally tying floors and walls together, without making the framework of the building so rigid that it breaks, rather than bending a little. This may mean more steel and less concrete.

Other measures are possible at greater expense. For example, foundations can be made deeper, connecting to bedrock (because this shakes less than soil), or they can be mounted on flexible pads to isolate the building from ground motion.

It is a tragedy and a scandal that the Turkish government knew all this. They have introduced a series of progressively more stringent seismic building codes, claiming to have learned lessons from the 1999 earthquake near the city of Izmit, near Istanbul, in which 17,000 people died.

But journalists are reporting how these building codes have been widely flouted in Turkey. Building in earthquake resilience adds maybe 20% to to costs of a construction project, so the temptation to ignore the regulations is obvious. In this case, the government not only failed to enforce its own building codes, but also encouraged non-compliance by allowing builders to pay a “construction anmesty” in return for officially sanctioned breaches of the codes.

Now charities are trying to raise hundreds of millions of pounds to help with the emergency response alone.

The Turkish government gambled with its peoples’ lives, and lost. The revenue from “construction amnesties” is far too little to pay for the reconstruction that is now needed, though I dare say the building industry will do nicely out of the extra work.

David Rothery is author of 'Volcanoess, Earthquakes and Tsunamis: A complete introduction' (2015). He has received funding from the UK Space Agency and the Science & Technology Facilities Council for work related to Mercury and BepiColombo, and from the European Commission under its Horizon 2020 programme for work on planetary geological mapping (776276 Planmap). He is author of Planet Mercury - from Pale Pink Dot to Dynamic World (Springer, 2015), Moons: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2015) and Planets: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2010).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.