A YouGov poll conducted in October this year asked respondents if they trusted the Conservative party. Some 68% said that the party could not be trusted and only 14% said that it could. This followed the ill-advised mini budget from former prime minister Liz Truss and former chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng that caused turmoil in financial markets and in the Conservative parliamentary party.

The trust levels for Labour in the same survey were a bit better, but even then 36% of respondents thought that the party could not be trusted compared with 26% who thought that it could.

The overall conclusion from the data is that the public does not trust British political parties at the moment, particularly not the governing party.

Does this matter? After all a certain amount of distrust in government is an important aspect of democratic accountability. If scrutiny of the government of the day is to work properly, then people should look at government with a certain amount of scepticism.

The problem is that when distrust reaches these kinds of levels, it will affect the ability of parties to actually govern. Much of governing is about persuading people to do (or not to do) things rather than enforcing policies with sanctions. The problem is that this becomes impossible if voters believe that they are being lied to all the time.

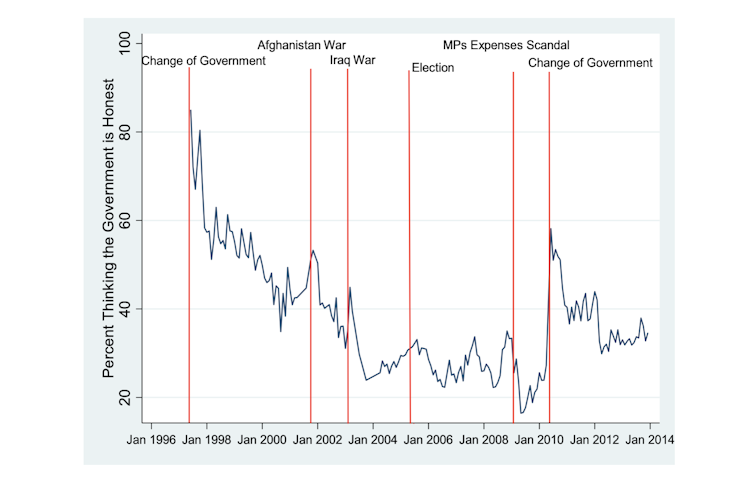

Interestingly enough, academic research shows that belief in the trustworthiness of governments is actually quite volatile in Britain. And it can change rather rapidly in response to events. This is illustrated in the figure below which measures the percentage of Britons who thought that the government of the day was honest and trustworthy in monthly surveys conducted over 17-year period from 1997 up to 2014.

Trust in the honesty of government 1997 to 2014

Shortly after arriving in office in 1997, Labour was trusted by more than 80% of the public. The party leadership immediately embarked on a daily battle to control the media agenda in its favour, a project led from the very top by Tony Blair and his spin doctor Alistair Campbell. This produced what amounted to a continuous election campaign – which has now become a standard feature of British politics.

However, as the chart shows, these relentless efforts to manage the news agenda in order to paint government policies in a positive light was ultimately associated with a rapid decline in trust in government, which highlights the dangers of excessive “spin control” in politics.

Specific events during this period also played an important role in influencing trust. The political turmoil associated with Britain’s involvement in the Iraq war in 2003 and the fact that many believed Blair lied to Parliament about the threat from Iraqi weapons of mass destruction preceded a sharp reduction in trust in government.

Expenses scandal

But the biggest threat to trust during this period came from the MPs expenses scandal in 2009, which arose from revelations published by the Daily Telegraph that many MPs were claiming expenses for all kinds of illegitimate things. These included upgrading second homes, non-existent travel expenses and a duck house in a garden pond. The scandal eventually led to criminal charges being brought against four MPs who were all subsequently jailed.

The scandal revealed that when backbench MPs from different parties are embroiled in behaviour which the public regards as unacceptable, the government of the day takes a good deal of the blame. The logic of this is simply that the government is in charge and so it should be held responsible for what happens. The behaviour in “partygate” during Boris Johnson’s tenure in Downing Street and the subsequent mistakes made by Truss and Kwarteng which spooked financial markets illustrates that governing parties which behave badly are likely to lose trust.

But it is also evident from the expenses scandal which involved MPs from different parties in Parliament can add to this distrust. This is because the public are likely to conclude that “they are all in it together” and “they are all as bad as each other”.

One interesting thing stands out in the data – namely that a change of government has a big effect on boosting trust, while a general election which the governing party wins does not. This was evident when Labour was elected in 1997 and also when it lost power in 2010. It looks like it will require a change of government to restore trust to reasonable levels, something which is urgently needed if British government is to be effective in the future.

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.