Donald Trump has picked former football player Scott Turner to lead the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. While not much is known about Turner’s positions as he awaits confirmation by the Senate, Trump’s selection draws attention to the incoming administration’s housing policies.

Those policies, evident in both the first Trump presidency and in comments made during the campaign, suggest an abiding faith in the private sector and local government. And they are likely to include deregulation and tax breaks for investment in distressed areas.

They also show a disdain for federal fair housing programs. These programs, Trump said on the campaign trail in 2020, are “bringing who knows into your suburbs, so your communities will be unsafe and your housing values will go down.”

‘Inharmonious neighbors’

In his September 2024 debate with Kamala Harris, Trump responded to a question on immigration by amplifying the discredited rumor that Haitian immigrants in Ohio were “eating the pets of the people that live there.”

“This is what’s happening in our country,” he added, “and it’s a shame.”

As a historian of public policy focused on urban inequality, I am struck by the similarity between Trump’s diatribe and the beliefs that instituted racial segregation in housing a century ago.

Trump’s false claim echoes the long-standing anxieties of white homeowners regarding immigration in general and African American migration specifically.

Both cases pit the interests of one set of residents against those of another.

First, there are the established, overwhelmingly white, residents – in Trump’s lingo, “the people that live there.” Then come the unwanted new arrivals whose sudden presence in American neighborhoods is seen as a menace to public health, welfare and property values.

Historically, the threats posed by “inharmonious” neighbors – as real estate agents and later federal housing agencies put it – have focused on immigrants and African Americans.

The surge in immigration to the U.S. at the end of the 19th century animated a notoriously nativist response from local governments and realty groups. It included early efforts at land-use zoning aimed at establishing economically and racially exclusive residential districts in cities. And it involved the first stirrings of white flight to the suburbs, especially in the rapidly urbanizing Northeast and Midwest.

Patchwork apartheid

But it was the Great Migration of African Americans in the first decades of the 20th century, coupled with the urban residential boom of the 1920s, that galvanized the peculiarly American alchemy of race and property.

During this period, many cities, beginning with Baltimore in 1910, experimented with explicitly racial zoning that designated neighborhoods for solely white or Black occupancy.

The Supreme Court struck these laws down in 1917 on the grounds that it invaded “the civil right to acquire, enjoy and use property.”

With the option of legally codified racial zoning closed, as I detail in my book, “Patchwork Apartheid,” the white reaction to the Great Migration turned to the private and piecemeal action of developers, real estate agents and homeowners.

The centerpiece was the widespread use of private contracts designed to prevent those “not wholly of the Caucasian race” from owning or occupying homes in “protected” neighborhoods.

This private resistance to integrated neighborhoods was occurring as new housing starts ballooned after the war, from 240,000 a year in 1920 to almost 1 million in 1925.

These restrictions took a variety of forms.

Suburban developers commonly imposed prohibitions on African American occupancy or ownership of new construction, especially in the rapidly growing cities of the Midwest. Existing residents of older neighborhoods facing racial transition in places such as Chicago and St. Louis would also impose racial covenants by petition.

In all these settings, as I detail in my book, racial restrictions were routinely attached to individual home sales by buyers, sellers or real estate agents. They hoped to ward off what white realty interests routinely referred to as “invasion” or “encroachment.”

The result was a sort of patchwork apartheid. It was crafted nationwide but stitched together parcel by parcel, block by block, subdivision by subdivision.

Stark racial segregation

My work on St. Louis has uncovered almost 2,000 racially restrictive agreements imposed between 1900 and 1950. By 1950, this patchwork of private restriction encompassed nearly two-thirds of the St. Louis region’s residential properties.

Their core logic was that occupancy by inharmonious neighbors constituted a “nuisance” use of property.

Before 1920, private property restrictions commonly included a general nuisance provision barring commercial uses, often listing trades offensive to the senses, such as a slaughterhouse or a junkyard, or to one’s morals, such as a tavern.

In response to the Great Migration, white realty firms in St. Louis and elsewhere simply appended “colored” occupancy to their list of nuisances.

For example, the uniform agreement used by the St. Louis Real Estate Exchange banned two classes of buyers or renters: “any slaughterhouse, junkshop, or rag-picking establishment” and “a Negro or Negroes.”

In the St. Louis subdivision of Cleveland Heights, a long list of proscribed nuisances was capped with the provision that no lot could “in any way or manner” be “occupied by any persons other than those of the Caucasian Race.”

Some restrictions elided racial categories and nuisances by restricting sales to residents considered simply “objectionable” or “undesirable.”

A common clause found in most Midwestern settings barred any “race or nationality other than those for whom the premises are intended.”

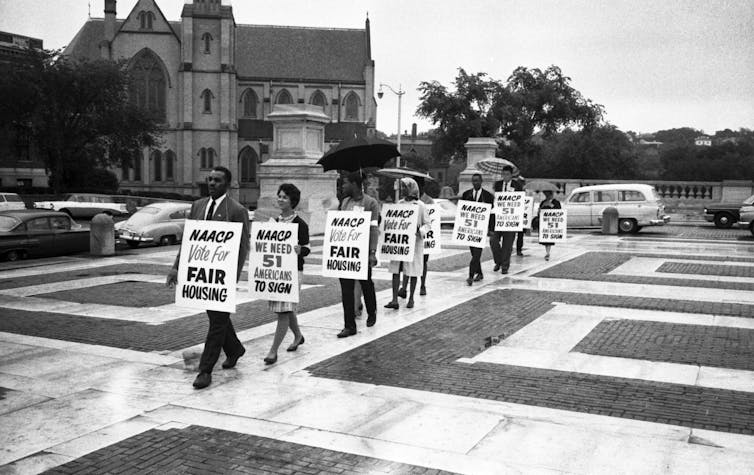

Such private restrictions were ruled an unenforceable violation of equal protection by the Supreme Court in 1948. And they were prohibited outright by the Fair Housing Act two decades later.

But the damage – stark racial segregation and a yawning racial wealth gap – was done. And the core assumptions about race and property lived on in the policies of private realty, lending and appraisal.

‘Your communities will be unsafe’

Trump’s debate outburst, in this respect, reflected a racial politics shaped as much by his real estate background as his political aspirations.

Trump inherited a property portfolio from his father that was already deeply committed to racial segregation and discrimination against African American tenants. Beginning in the 1970s, his family’s New York realty practice was notorious, and routinely sued, for violations of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, meant to check private discrimination in private realty.

As president, Trump continued to erode the notion of fair housing for all.

In 2020, he jettisoned an Obama-era rule requiring that cities receiving federal housing funds affirmatively address local discrimination and segregation.

“The suburb destruction,” he promised at the time, “will end with us.”

Trump housing 2.0

Turner, as the next HUD secretary, is poised to pick up where the first Trump administration left off.

Consider the housing agenda of Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s sweeping blueprint for the second Trump administration. Penned by Ben Carson, Trump’s first HUD secretary, it proposes a radical retreat from federal “overreach” that would include gutting anti-discrimination provisions in federal programs and deferring to localities on zoning.

It would also bar noncitizens from public housing and reverse “all actions taken by the Biden Administration to advance progressive ideology.”

At the time of Trump’s Springfield, Ohio, comments, the apocryphal specter of pet-eating immigrants seemed but one more oddity in a campaign punctuated with them.

But it was more than that. It was the preamble to a new chapter in the U.S.’s long history of discriminatory neighborhood “restriction” or “protection.”

Colin Gordon receives funding from The Russell Sage Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Mellon Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.