In the 1976 political drama All the President’s Men, Robert Redford’s Bob Woodward meets the secretive FBI source, Deep Throat, in a parking garage to ask him what he knows about the Watergate break-in. Deep Throat – in real life, the FBI deputy director Mark Felt – is ominous and taciturn, refusing to say all that he knows. “I have to do this my way,” he tells Redford. “You tell me what you know, and I’ll confirm.” But he offers a blunt assessment of the inner workings of the Nixon administration. “Forget the myths that the media has created about the White House,” Deep Throat tells Woodward. “The truth is these are not very bright guys, and things got out of hand.”

Few moments in history, including the Watergate scandal, have done so much to puncture the dignified mystique of American government as Donald Trump’s frantic, cynical and preposterous attempts to hang on to power after losing the 2020 election. The indictment against him related that effort, unsealed on Tuesday by the office of special counsel Jack Smith, charges Trump with engaging in three conspiracies: to defraud the United States in seeking to overturn the election, to obstruct the government in seeking to derail the January 6 proceedings, and perhaps most meaningfully, to deprive American voters of their right to have their votes counted. The charges are serious; the violence was deadly. But every one of the indictment’s 45 pages evokes Deep Throat’s words: these are not very bright guys.

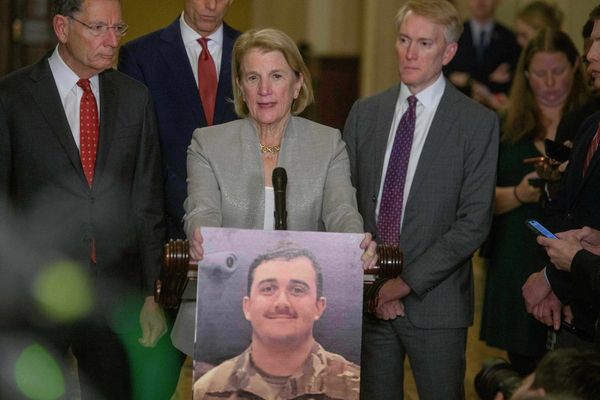

The document unsealed on Tuesday charges only Trump. But it also implicates six co-conspirators. These include a justice department official, probably the then assistant attorney general Jeff Clark, along with an unidentified political consultant. Also implicated are four Republican lawyers, seemingly including Trump’s personal attorney Rudy Giuliani; the law professor John Eastman, who concocted the false theory that the vice-president had the authority to intervene in the electoral vote counting ceremony; Ken Chesebro, an author of the fake electors scheme; and the quack pro-Trump conspiracy theorist Sidney Powell.

It was with these accomplices that the special counsel alleges that Donald Trump embarked on a series of frauds, fabrications and cockamamie schemes to reverse the election outcome between November 2020 and early January 2021. That project had multiple successive fronts, with the conspirators moving on to new strategies as the previous ones failed. They tried to use the justice department to pursue frivolous and fraudulent allegations of election malfeasance; then they tried to conscript state officials into advancing false claims of election fraud; then they tried to send fake electors to congress; finally, they tried to stop congress from certifying the election results on January 6.

All the while, they flooded the media with what the indictment calls “knowingly false” claims that the election was stolen, in the hope of creating public distrust in the election outcome and pressure on the officials who they believed could reverse it. None of these schemes were especially well-thought-out, and none would have been plausible without both a willingness by many Republican officials to lie on Trump’s behalf, and a willingness by many Trump supporters to commit violence. But those, sadly, are not in short supply.

That Trump and his co-conspirators failed in their effort to subvert the election was largely a matter of luck; that they are now being charged in this most significant of Trump’s crimes was not at all guaranteed.

Much of what is recounted in the indictment is not new. The facts presented by the special counsel hew closely to those laid out by the House January 6 committee in a series of televised hearings last year, and Smith, like that committee, spends a great deal of time eradicating any doubt about Trump’s state of mind or his certainty that his own statements about the election were false. But the indictment does contain new tidbits of information gleaned from the special counsel’s investigation, ones that make both the incompetence and the malice of the conspiracy plain. Copious testimony and contemporaneous notes provided by Mike Pence, for example, make it clear the extent to which Trump’s former vice-president, against whom he incited a murderous mob, is cooperating with the special counsel. Emails obtained by the investigation also add texture to the story of the election subversion effort. One campaign adviser, tasked with encouraging false claims of election fraud in Georgia, wrote in an email that the allegations being advanced by the Trump camp were “conspiracy shit beamed down from the mothership”. Not exactly the words of a man convinced of the righteousness of his own cause.

More disturbingly, the indictment reveals the extent to which Trump and his co-conspirators were conscious of the possibility that their actions might lead to violence, and that violence might be required to achieve their goals. This does not seem to have disturbed them, or even to have prompted much hesitation.

Pence’s lawyers allegedly told John Eastman that if the vice-president usurped the January 6 certification ceremony as Eastman wanted him to, the result would lead to a “disastrous situation” in which the election would “have to be decided in the streets”. On 3 January, just days before the riot, a member of the White House counsel’s office told Jeff Clark that if the president tried to remain in office as planned, there would be “riots in every major city in the United States”. To which Clark allegedly replied: “Well, that’s why there’s an Insurrection Act.” Clark was referring to a law that empowers the sitting president to deploy the military to suppress unrest.

It has long been clear that far-right extremist militia groups, such as the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers, planned for violence at the Capitol on January 6; it has been less clear the extent to which the Trump camp communicated with these groups, if at all, about the event and that possibility. It was a connection that has long been speculated about, but which the House committee on January 6 did not firmly make, and the special counsel’s indictment doesn’t, either.

In December 2020, just weeks before Clark’s conversation, the leader of the Oath Keepers had called on Trump to invoke the Insurrection Act. This rhyming thinking doesn’t indicate coordination, but it does suggest a sympathy of mind, and of tactics, between the extremist groups and the Trump camp. It is an affinity that will only become clearer if Trump becomes the Republican nominee again, as he is all but certain to. These are not very bright guys, but they’re still quite dangerous ones.

Moira Donegan is a Guardian US columnist