A Georgia special grand jury has finished its work investigating whether former president Donald Trump and his allies committed crimes when trying to overturn the 2020 election results.

While special grand juries cannot themselves issue indictments, they can recommend district attorneys do so. This and other recent news about Trump’s mounting legal problems has led to a number of legal experts and political observers saying that Trump could soon be indicted.

Trump, meanwhile, faces several other criminal investigations that could also result in indictments. The Department of Justice is investigating Trump for retaining government documents in violation of several federal laws.

And the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol referred Trump to the Department of Justice in December 2022, citing multiple likely criminal violations in his role of orchestrating an attack on the Capitol. The Department of Justice’s special counsel is now investigating.

Trump, who may become the first former president of the United States to be indicted by a court of law, is not the first modern president with legal problems. But the question of whether a president – sitting or former – should be charged with a crime has come up three times in the last half-century.

As a legal scholar, I understand the important questions raised about the rule of law within U.S. democracy by the possible indictment of a former president.

The rule of law means that no one is above the law. It ensures that the rules are made by and for the people. Those rules are enforced equally and adjudicated through well-established procedures. For the rule of law to prevail, any decision to indict a former president – or not to – has to be credible, independent and supported by evidence.

Being a current or former president matters

Presidential misconduct is not new.

Presidents have engaged in unlawful activity. Some have even run into legal problems while in office. But their legal problems are often settled by the time they leave office and fade from the public’s memory.

The perseverance of Trump’s legal problems raises important new questions about how to deal with misconduct by a former president.

This matters, because federal law treats former presidents differently from sitting presidents. Former presidents do not retain all the legal advantages of being president. For example, former presidents can try to assert executive privilege to shield certain documents and information from Congress, courts and the public to protect the nation, but courts have limited their ability to do so.

The question of whether a sitting president can be indicted remains unresolved. In 2000, the Department of Justice adopted a policy against indicting a sitting president. The policy protects presidents while they are in office so they can fulfill their constitutional duties.

But it is tradition, not law or policy, that has kept former presidents from indictment in the past 240 years.

The legal arguments against indicting a sitting president – namely that it would undermine the capacity of the executive branch to perform its constitutional functions – lose weight once a president leaves office. A former president becomes a private citizen and no longer has any duties under the Constitution.

Legal trouble for sitting presidents

A few presidents have faced legal problems while in office, including Republican Richard Nixon and Democrat Bill Clinton.

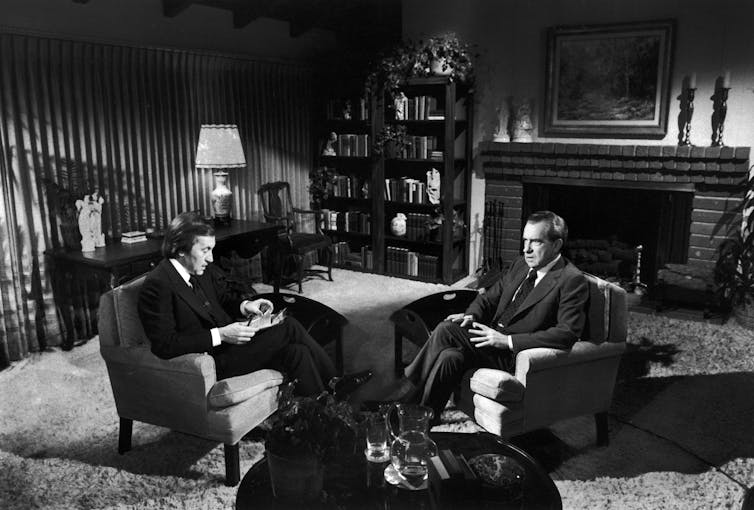

Nixon famously ran into legal trouble after his reelection campaign burglarized and bugged the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in June 1972 – and he subsequently participated in the effort to cover up the scandal.

Nixon resigned in 1974 before the House of Representatives could have potentially impeached him – or the Senate could have convicted him and removed him from office for his crimes of obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress.

Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski, who was investigating the Watergate scandal, struggled with the question of whether a court can indict a sitting president.

The U.S. Constitution does not say that the president is immune from ordinary processes of the criminal law. It does, however, provide for impeachment and removal from office.

Some believe that because the Constitution establishes an impeachment process to address presidential misconduct, it should take precedent over a criminal indictment. Others worry that indictment would interfere with a president’s ability to fulfill his or her constitutional duties.

Jaworski left this legal question open and chose not to indict Nixon in 1974. He transmitted the evidence he had gathered on Nixon’s involvement in Watergate to the House so it could pursue impeachment proceedings.

The grand jury that was also investigating the Watergate scandal, however, voted in June 1974 to name Nixon as an unindicted co-conspirator in an alleged conspiracy to obstruct justice. It also recommended indicting seven men involved in the crime.

Nixon’s successor, President Gerald Ford, then faced the question of how to deal with Nixon’s misconduct after his predecessor resigned the office. Ford didn’t have the power to indict, but he could pardon Nixon for his alleged crimes. Ford decided that it was in the best interest of the country to move on from the Watergate scandal and to not allow prosecutors to indict Nixon.

Shortly after Nixon’s resignation, Ford granted a full, free and absolute pardon to Nixon in September 1974 for all offenses committed during his tenure as president. Ford’s pardon ensured that Nixon would not face indictment as a former president.

Another kind of legal trouble

Clinton was never indicted, but he faced serious consequences for his presidential misconduct. His legal problems related to his treatment of and relationships with several women who were not his wife.

Clinton was accused of lying in court proceedings in a sexual harassment case filed against him. His alleged lying led to his impeachment for lying under oath to a federal grand jury and obstruction of justice. The Senate voted not to convict him, and thus he was not removed from office. A federal district judge held Clinton in contempt of court for making false statements in deposition testimony in the case.

Unlike Nixon, Clinton paid a price for his presidential misconduct. An Arkansas Supreme Court committee sued him for his behavior while in office and asked that Clinton be disbarred for his behavior.

Clinton settled the suit by agreeing to a five year suspension of his law license, a $25,000 fine and public acknowledgment that he had violated the Arkansas Rules of Professional Conduct. He accepted a punishment far harsher than the reprimand normally given in similar situations, but escaped criminal prosecution.

Preserving the rule of law

Trump now faces multiple criminal investigations that could result in an indictment. No former president has faced so many possible indictments.

Any decision for or against indicting Trump could threaten the rule of law if it is not carefully considered and supported by the evidence. As weighty and historic as the decisions about indicting Trump may seem, they reflect the country’s larger struggle in navigating how to deal with presidential misconduct.

The next steps in Trump’s legal saga will be key in determining how our democracy decides to hold former presidents accountable for their misconduct.

Kirsten Matoy Carlson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.