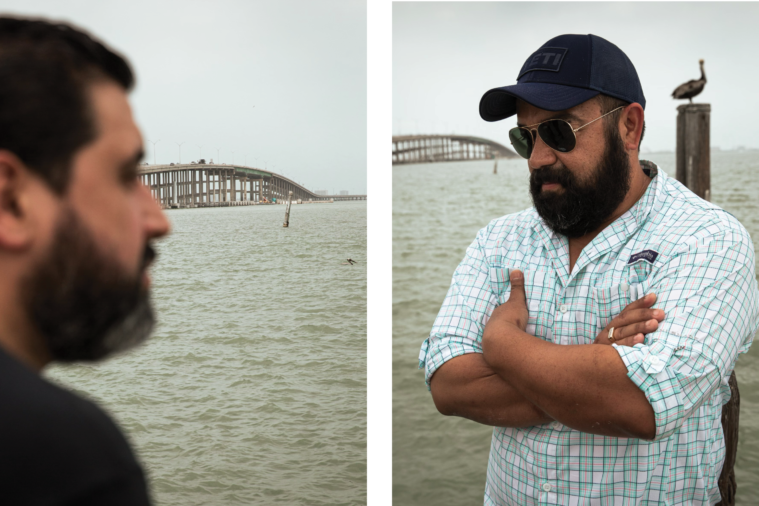

Robert Espericueta and his cousin Roland Moya stand outside the Lighthouse Assembly of God in Port Isabel, a sleepy town of roughly 6,000 people in South Texas. It’s a weekday in mid-April, overcast but bright, and the wind is coming on strong. The sound of waves crashing in the Gulf Coast bay just a few blocks down the road carries in the salty air.

Both in their early 40s, Espericueta and Moya are here to meet with Pastor Steven Hyde, who they haven’t spoken to in decades. Hyde rolls up in his white pick-up truck and steps out. As he walks up to Espericueta and Moya, they greet each other with warm hugs.

“Pastor Hyde, how old are you now 20 years later?” Moya says, laughing.

“You don’t wanna know!” replies Hyde, in a strong East Texas accent, waving everyone into the church. For the past few months, Espericueta has been doing a lot of this kind of thing, digging up old memories and meeting with old acquaintances, trying to piece together a night 20 years ago that has haunted him since.

On September 15, 2001, just four days after the planes struck the Twin Towers, Espericueta and Moya witnessed another tragedy. One of far less notoriety in the national eye, but just as present in South Texas lore. Early that morning, a large towing barge crashed into the side of the Queen Isabella Causeway—the bridge built in 1974 that connects Port Isabel to South Padre Island over 2.4 miles across the Laguna Madre—causing part of it to collapse. Eight people died.

Espericueta, Moya, and two other men were out fishing on the water that night and saved the lives of three people. Following a flurry of litigation, the fishermen’s attorney led them to believe they were bound by a gag order from speaking publicly. As the 20-year anniversary of the accident approaches and they started digging through records, they could find no such order. Now, they want to tell their side of the story.

That’s what brought them to Hyde’s doorstep. In February, alongside Joshua Moroles, founder of McAllen-based Alamo Digital Agency, Espericueta launched a podcast called “The True Story of The Queen Isabella Causeway Collapse” that chronicles the events of that night and its aftermath. Hyde, who met the fishermen and offered them a prayer the morning of the accident, had agreed to be a guest on the show to rehash his role in their story. Filled with anxiety and fear after the collapse, Espericueta and Moya say that prayer was the only peace they felt in all the chaos.

Thousands of people have listened as Espericueta, Moroles, and their guests have poured over documents from the case in order to determine what all went wrong that day and maybe—just maybe—get some closure.

Anyone who has been to South Padre Island has likely had to cross through Port Isabel, which spans all of 14 square miles. It’s an old town, established after the Mexican War of Independence, full of locals who work on the island and relies heavily on traffic from beachgoers to stay running. The people on the island work in the mainland and get their groceries from the Port Isabel Walmart and HEB.

Nearly everyone from the Valley remembers the bridge collapse. I grew up in McAllen, about an hour and a half from Port Isabel, and to this day, I always roll down my windows before crossing the bridge, which I decided as a child would save me from the same fate as the people who were lost that night. Friends have their own memories: one got trapped on the island with their family; another’s uncle got stuck on the bridge, waiting for the accident to clear. When I asked my mother what she remembered, she said, “Well, we all thought it was another terrorist attack.”

Another friend, who grew up in Harlingen, said he had always heard that the barge driver was drunk and that’s why he crashed into the pillars. “Why did we think that?” he says now.

BECOME A MEMBER

Help make journalism like this happen.

Though the Rio Grande Valley has a population of 1.3 million, everyone seems to know everyone. Stories have a way of spreading from town to town, each iteration more dramatic than the last. Like the infamous story of the woman who was said to have danced with the devil in the 1970s at the club Boccacio’s—her parents warned her not to go out during Holy Week, according to lore, and she ended up dancing with a handsome stranger who smelled of sulfur and had one hoof and one chicken’s talon in place of feet—here, legends become fact and facts become legend.

But the story of the causeway collapse got overshadowed by what happened in New York. Even the anniversary news stories that commemorate the wreck every five years have never been complete.

The night of September 14, 2001, started like any other. Robert Espericueta, then 21, had recently bought a Glastron speedboat. Just a few days after watching the Twin Towers collapse, he wanted to let off some steam and fish in the bay and asked his cousins, Leroy and Roland Moya, and Roland’s then-brother-in-law, Tony Salinas, to come with him.

The National Weather Service expected a rip tide and issued a warning for small boats, but the fishermen didn’t care. They packed up the boat and made their way out into the water around 10 p.m.

The bay was quiet, the water was still, and the fish were biting. The fishermen posted up on the northwest side of the causeway, closer to Port Isabel. The lights that usually illuminated the road on the causeway were out, making the night nearly pitch black, except for the light of the moon reflecting on the water. All they could see were the little dots of red tail lights traveling across the bridge. “They looked like little cherries floating in the darkness,” Espericueta remembers.

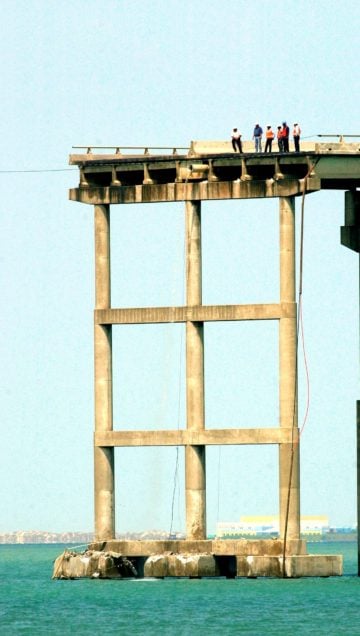

Then, around 1 a.m., they heard a long, bellowing groan of metal colliding with concrete. They were less than a mile away from the bridge when they saw it: a towing barge, which maneuvers other vessels, coming from the south had run into one of the pillars at the peak of the causeway. The towing barge, Brown Water V, halted and the concrete of the causeway came tumbling down, leaving a gaping hole about 160 feet wide. There was no way to warn the drivers speeding along the bridge what was waiting for them.

The barge captain, David D. Fowler from Mobile, Alabama, had lost control of the ship. Contrary to many rumors, alcohol and drug tests would later prove he was sober. He told police that the towing barge hadn’t been properly maintained and didn’t have the necessary horsepower to redirect. On top of that, the rip tide had crept in and the green navigation lights on the causeway that help guide ships under the bridge weren’t on. “When I saw the bridge coming down, I kept blaring my horn and flashing my lights and trying to get the people to stop coming,” Fowler said, according to a story written by the Associated Press at that time.

The first car fell through the hole. Then another. And then another. A total of 11 people drove straight into the dark ocean from roughly 80 feet above the water.

The fishermen watched it all happen, screaming out to the drivers to stop. But their calls were futile. Despite the risk, they steered their boat in the direction of the cars and called 911 for help. The Coast Guard station on South Padre Island was less than 4 miles away but it would be another two hours before the Coast Guard arrived. “I’ll never know why it took them so long to get to us,” Espericueta says.

By the time help arrived, the group of young fishermen had managed to reel in three of the people who had fallen in: Rene Mata, Brigette Goza, and Gustavo Morales. Espericueta says the Coast Guard arrived in a large ship that towered above their small craft, making it nearly impossible to transfer the injured parties to the rescue boat. Instead, the Coast Guard left the survivors in the fishermen’s care and sent them to the mainland.

The eight victims the fishermen could not rescue were Barry Welch, 53, and Chealsa Welch, 23; Julio Mireles, 23; Stvan Rivas, 22; Robin Leavell, 29; Hector Martinez, 32; and Robert Harris, 46. Gaspar Hinojosa died on his way to the hospital from the injuries he sustained. Help had come too late.

Hours after the accident, after the fishermen returned to land, they remember seeing families of the victims standing by the bridge, signs in hand, calling out for their missing loved ones. After a few hours of questioning by law enforcement, the fishermen made their way home.

The U.S. Coast Guard launched an investigation into the events of that night and a four-year-long class action lawsuit ensued. Dozens of lawsuits were filed against the American Commercial Barge Line (ACBL) and the company it hired to tow its boats, Brown Water Towing Service, for negligence. There were 17 plaintiffs in the case, including the families of the eight who died, the three survivors, and the four fishermen.

The plaintiff’s lead attorney, Ray Marchan, had hoped to prove that the barge line, said to be insured for $500 million, hired a tow company that it knew had problems. But U.S. District Judge Hilda Tagle dismissed ACBL from liability and instead focused on Brown Water, which was found guilty of having overstated its towing barge’s horsepower, resulting in the accident. In the end, the plaintiffs received a total of $9 million, less than half of the company’s insurance policy.

“Once that was divided up, it was basically nothing,” Espericueta says. He feels wronged by the group of attorneys handling their case, including the attorney specifically assigned to the fishermen, Frank Enriquez. Enriquez died by suicide in 2019 and Marchan died by suicide in March 2013: A few days after being convicted of racketeering, he jumped off the Queen Isabella Causeway.

I couldn’t find any record of David Fowler, the barge captain, to ask him about that night. According to an AP report, Sheldon Weisfeld, Fowler’s attorney, said Fowler suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and ended up in and out of mental health facilities following the accident. Though the Coast Guard’s report acknowledges the multiple contributing factors that led to the accident, they still attributed captain error as the main cause. The Coast Guard did not pursue criminal charges against Fowler, though they did strip him of his license.

For months, the incident hung over the island and Port Isabel. Residents on the island struggled to make it to work on the mainland, taking a daily ferry across the bay. Businesses closed down due to the lack of tourists. It took the state all of two months to repair the causeway. The only physical evidence that anything transpired is the bump you feel when driving over the segment of newer concrete.

To this day the causeway is still the main artery keeping South Padre Island and Port

Isabel connected, though a second bridge has been in talks for years. There are a number of safety measures in place to help prevent another disaster. Since 2001, the Texas Department of Transportation has required regular inspections and more robust maintenance of bridge lighting. In 2004, towing vessels were re-classified as inspected vessels, requiring approval from the U.S. Coast Guard. That same year, the county installed a fiber-optic warning system that automatically alerts local authorities if the bridge starts to shake or a piece breaks off. It also sends signals to gates that close off the bridge and turn on flashing lights that warn drivers.

But without these systems in place in 2001, the night of the Queen Isabella Causeway’s collapse ended in devastation. If not for the fishermen out on the water, there might not have been any survivors. Last year, on the eve of the 19th anniversary of the collapse, an anonymous bomb threat was made threatening the causeway. Authorities shut down the bridge for a few hours while investigating, though nothing was found. Later that evening, community members gathered at the base of the causeway in Port Isabel to remember those who died.

Espericueta dreams about that night often. He still feels guilt over the people he couldn’t save. The smell of gasoline sometimes triggers memories. On top of that, the fishermen are haunted by the memory of a “woman in white,” who they recall beckoning to them in the water before disappearing, though all the victim’s bodies were accounted for and there is no record of her.

Espericueta says none of those who came out alive got the mental health help they needed. For a short period during the case, the men spoke to a therapist paid for by the state. But as soon as the settlement was reached, they were left on their own. Espericueta says he wishes he could have received some sort of “lifetime therapy” instead of his settlement money, which ended up being about $34,000. “I didn’t know then I would carry this with me forever,” he says.

Morales, one of the survivors who came on the podcast, says after the accident he felt guilty, asking God, “Why am I here and the others are not?” According to Espericueta, Rene Mata, another survivor, isn’t happy that the men are opening up the past. But Espericuerta and Moya say that finally talking about what happened out loud has been cathartic.

The fishermen feel like a part of them was stolen that night and yet there’s no one to pin the blame on. Nowhere to let their grief go. That evening is still shrouded in mystery, assumptions, and rumor. Almost everyone in South Texas knows the causeway collapsed, but few know the fishermen exist. We know people died, but the majority of us barely know their faces, or their names. They’re a part of the story that went missing as legend spread.

Back inside the church, Espericueta, Moya, Moroles, and Pastor Hyde wrapped up their podcast after about an hour of talking. After they turn off the recording, Hyde asks if he can say a prayer with them. Each puts a hand on each other’s shoulders and bow their heads.

“Father,” Hyde starts, “we want to ask for your healing and peace to be with the families of the victims. Thank you for the opportunity to be here today with these men. I pray for your protection and peace over them. Thank you for the last 20 years.”

Then, all of them together, “Amen.”