Tropical Storm Debby was moving so slowly, Olympians could have outrun it as it moved across the Southeast in early August 2024. That gave its rainfall time to deluge cities and farms over large parts of Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas. More than a foot of rain had fallen in some areas by early Aug. 7, 2024, with more days of rain forecast there and into the Northeast.

Mathew Barlow, a climate scientist at UMass Lowell, explains how storms like Debby pick up so much moisture, what can cause them to slow or stall, and what climate change has to do with it.

What causes hurricanes to stall?

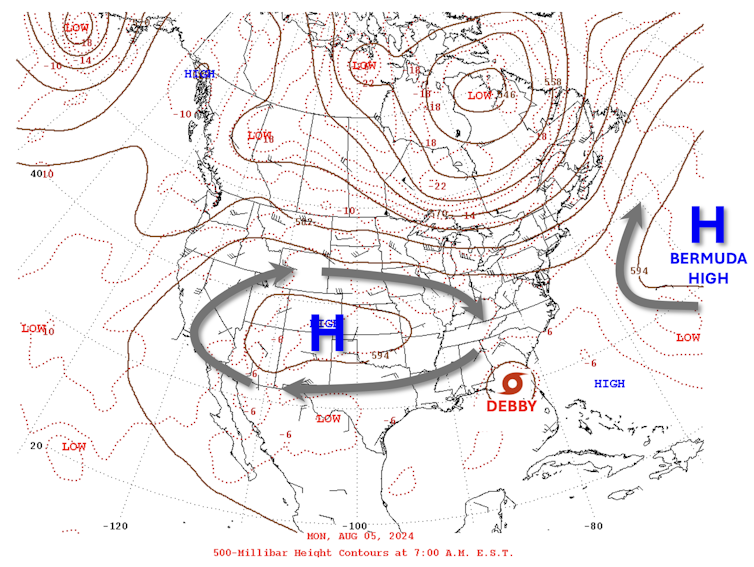

Hurricanes are steered by the weather systems they interact with, including other storms moving across the U.S. and the Bermuda High over the Atlantic Ocean.

A hurricane may be moving slowly because there are no weather systems close enough to pull the hurricane along, or there might be a high-pressure system to the north of the hurricane that blocks its forward movement.

In this case, a high-pressure system over the western U.S. was slowing Debby’s forward progress, and the Bermuda High – which is a large, clockwise circulation of winds that generally runs up the East Coast – wasn’t close enough to be a factor.

That’s similar to what happened with the remnants of Hurricane Harvey in 2017, one of the best-known examples of a stalled hurricane. High pressure over the U.S. blocked its forward movement, allowing it to drop more than 50 inches of rain on parts of Texas.

Slower-moving storms have longer to rain over the same area, and that can dramatically increase the risk of flooding, as the Southeast is experiencing with Debby.

How is Debby carrying so much rain?

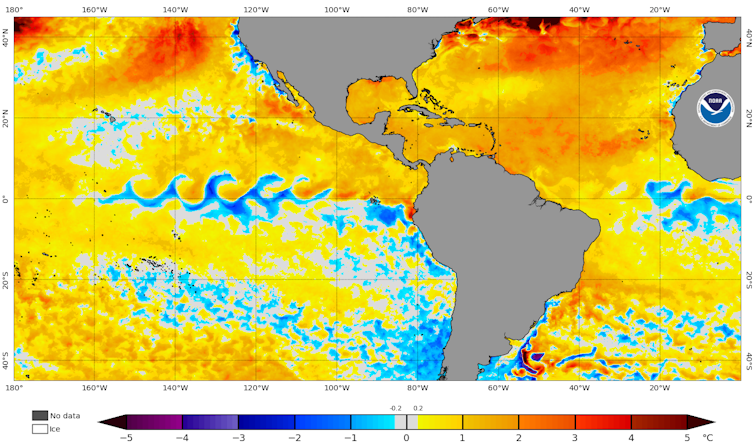

The surface temperatures of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico have been much warmer than average for the past year. Right now, there is a very broad area of exceptionally warm sea surface temperatures there, which means a lot of evaporation.

The air is also warmer than average, and warm air can hold a lot more moisture.

So, more evaporation from a warmer ocean is pumping more moisture into warmer air, which can hold more. This more-more-more has resulted in a lot of moisture in the air over this large area, from the Gulf of Mexico across the East Coast, and that’s the area that Debby is moving through. The storm is pulling in exceptionally high moisture from all directions – it’s the perfect environment for producing very strong rains.

That warm, moist air also extends up the East Coast, which is why the Mid-Atlantic and potentially the Northeast are forecast to see heavy rain and flooding as the storm pushes northward and interacts with other weather systems.

Debby is also moving near the coast. Since there is more water in the air over the ocean, this means the storm can stay stronger longer because it has a reservoir of fuel. If Debby had tracked inland more strongly, the storm would have died out more rapidly.

How is climate change affecting tropical cyclones?

Human-caused climate change is warming the ocean and atmosphere. That warming comes largely from the burning of fossil fuels, which emit greenhouse gases that trap heat near Earth’s surface.

The combination of warmer ocean and warmer atmosphere can result in higher rainfall rates and storms that intensify more rapidly.

There is also evidence that hurricanes affecting the U.S. are slowing in their forward motion and that this may be linked to climate change, but that link is not yet well understood.

Without a rapid reduction in fossil fuel emissions, these storms and their rainfall will continue to intensify. The good news is that humanity knows how to reduce emissions, and efforts are starting to move the world in that direction.

What’s in store for the Northeast from Debby?

Tropical Storm Debby is forecast to continue moving slowly over the Southern U.S. or just offshore for a few days, with a high risk of excessive rainfall and the potential for catastrophic flooding in areas of the Carolinas in particular.

Substantial rainfall is also expected over parts of the mid-Atlantic and Northeast. The area from Philadelphia to New York City is already under flood warnings ahead of the storm, in part because of a frontal boundary that’s allowing tropical moisture to build up there.

Once Debby moves through and interacts with other systems, it is forecast to move faster and head toward Atlantic Canada, leaving vast areas of flood damage in its wake.

Mathew Barlow has received funding from the US National Science Foundation to study extreme precipitation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.