Jamaican music from the late Sixties and early Seventies – a key time for its popularity here in the UK – is pretty much synonymous with one label: Trojan Records.

The British reggae specialist holds two claims to fame: not only helping the island’s culture in the face of critical indifference and establishment suspicion, but also easing barriers for multicultural communities in the teeth of racism and rabble-rousing.

“Trojan united black and white youth on the streets, dance floors and at school,” recalls Don Letts, the British broadcaster, filmmaker and reggae DJ, adding that the label “sowed the seeds for the UK’s love affair with Jamaican music”.

Yet Trojan Records’ 50th anniversary this month is also a chance to look again at how the label also suffered chronic mismanagement, and bore the brunt of criticism regarding treatment of Caribbean artists in Britain – unfairly, argues a long-term employee of the label.

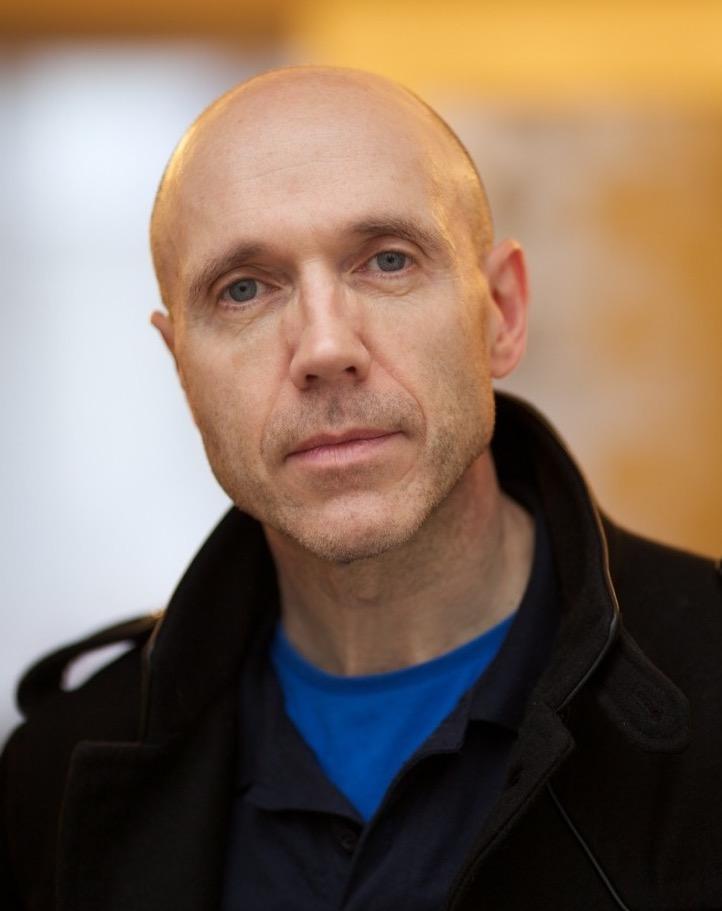

Laurence Cane-Honeysett, who first worked at Trojan, is now a consultant for the label and knows as much about its history as anyone. At the heart of events to mark the birthday, he wants to celebrate what Trojan achieved against the odds from a cramped warehouse in Willesden, northwest London.

“This story is a real one-off,” he says. “Trojan introduced reggae to the world by making its up as it went along; its achievements far outstretched its resources. The impact on Jamaican society was huge, because loads of money went back there to finance its music industry, but it was the first music here that crossed [racial] boundaries.”

The genre’s precursor, ska, broke internationally in 1964 with Millie Small’s indelible “My Boy Lollipop”, which launched one of Trojan’s mother companies, Island Records, in the UK. The sound gained a foothold, albeit fitfully, thanks to a coterie of minor labels originally servicing the Windrush generation of immigrants, then the soul-loving mods seeking novel flavours.

This was a challenging market: ska was disparaged by the music press and ignored by radio, with the focus on singles rather than albums. Plus many outlets for Jamaican music were not registered for the Top 40, lessening the music’s profile further.

One reliable source of tunes was Kingston-based producer Duke Reid, who in 1967 was given his own Island subsidiary named Trojan. Except Reid licensed many of its releases to rival imprint Doctor Bird, hoping to benefit twice from the same tracks.

Island boss Chris Blackwell soon ended that relationship, but was also becoming distracted with the potentially more lucrative rock scene (which boasted greater album sales) with groups such as Traffic and Fairport Convention.

A year later, Island merged its Jamaican roster with that of a rival, Beat & Commercial, which owned its own chain of specialist outlets. Trojan was reborn and ready to take on the industry big shots.

Cane-Honeysett, author of a forthcoming book on the label, explains that the combination of shops and Island’s distribution had “laid the foundations for success; combining all their Jamaican contacts, you had a virtual monopoly”.

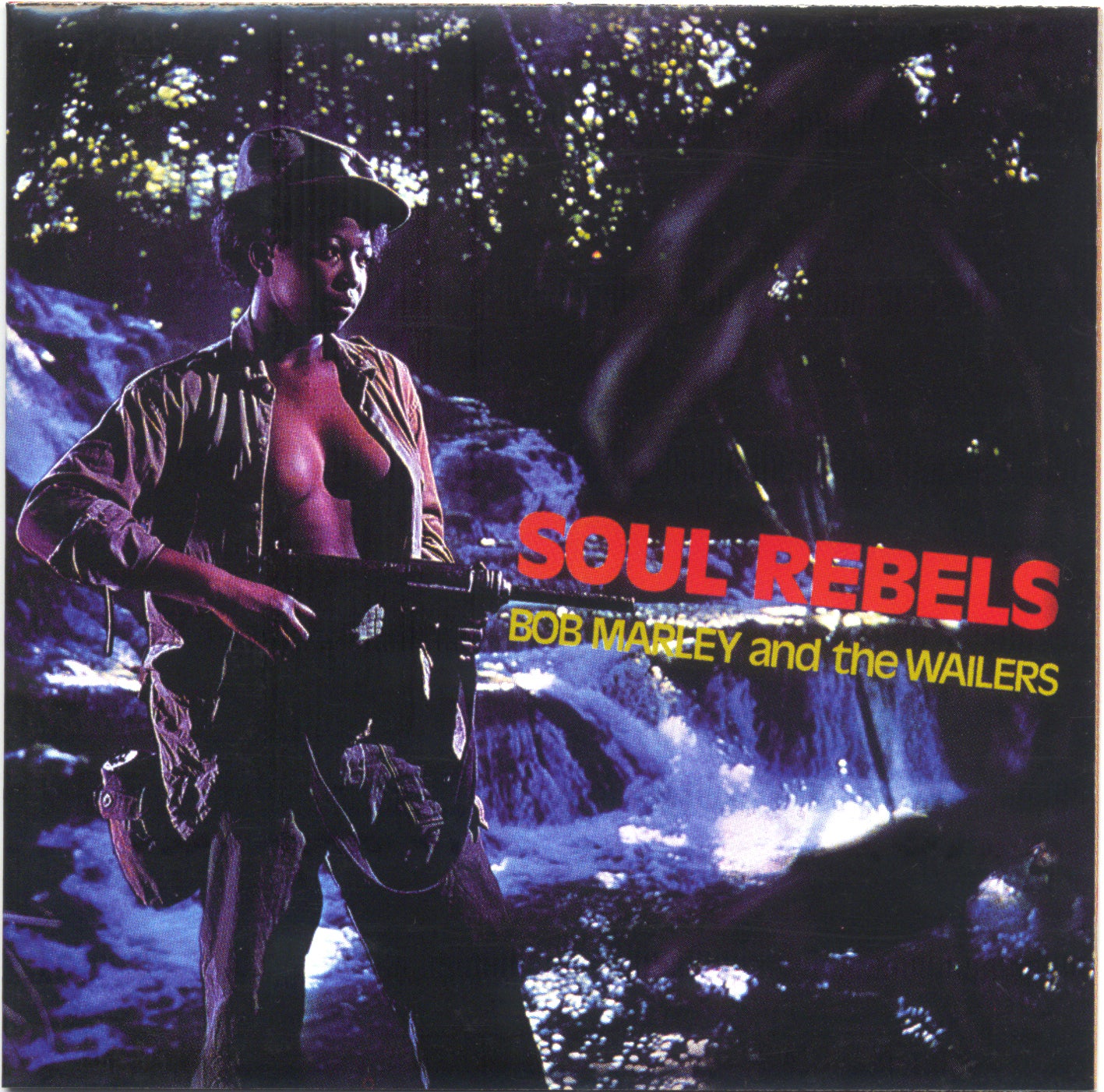

At first, though, the nascent label struggled to make an impact – despite a lineup that included a young Bob Marley.

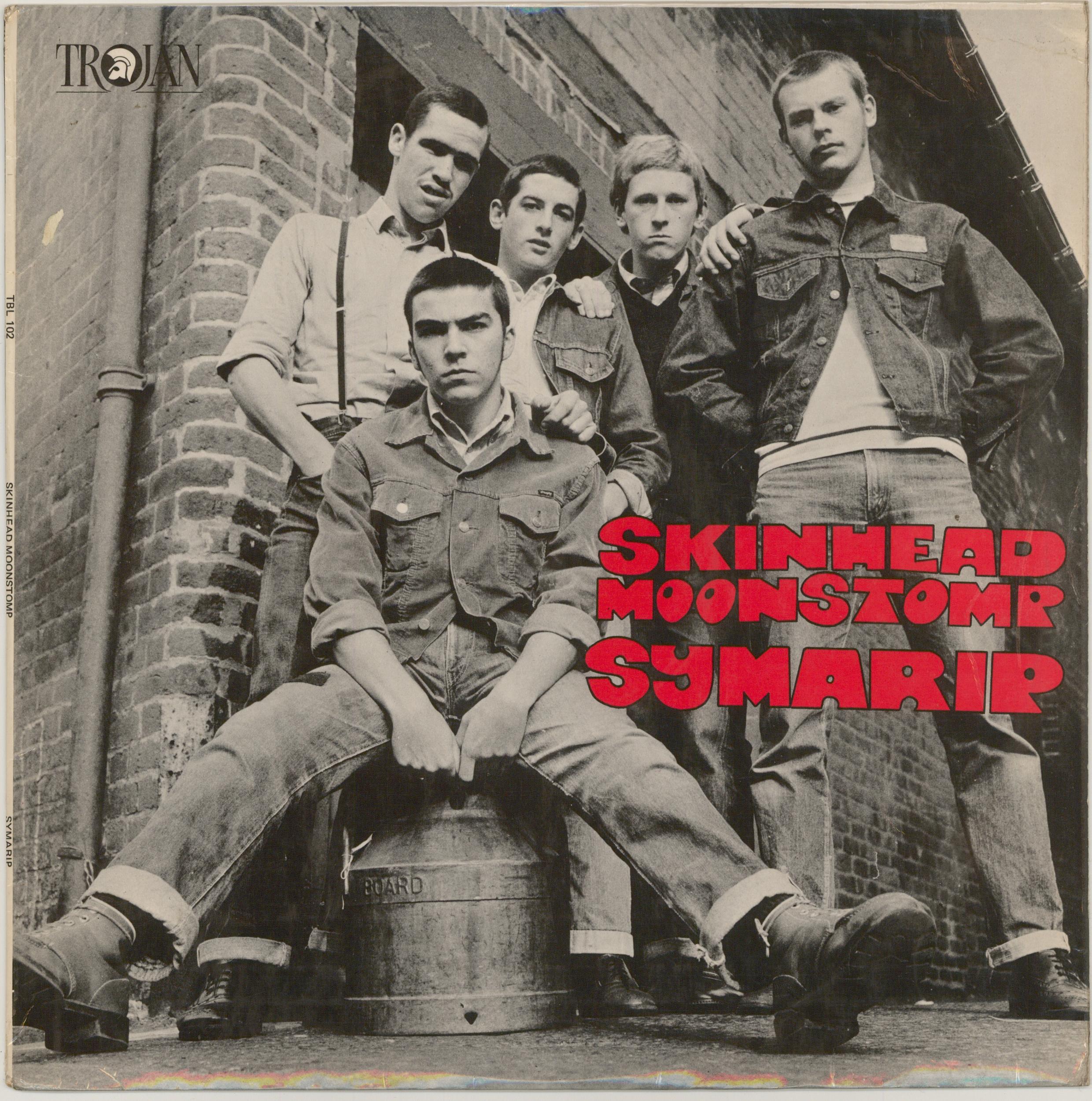

But a younger, working-class audience was becoming energised by Jamaican music. Reacting against the peacock colours, long hair and expansive sounds of the late Sixties, they shaved their heads, laced up bovver boots and stomped to ska and reggae. The first skinheads had arrived.

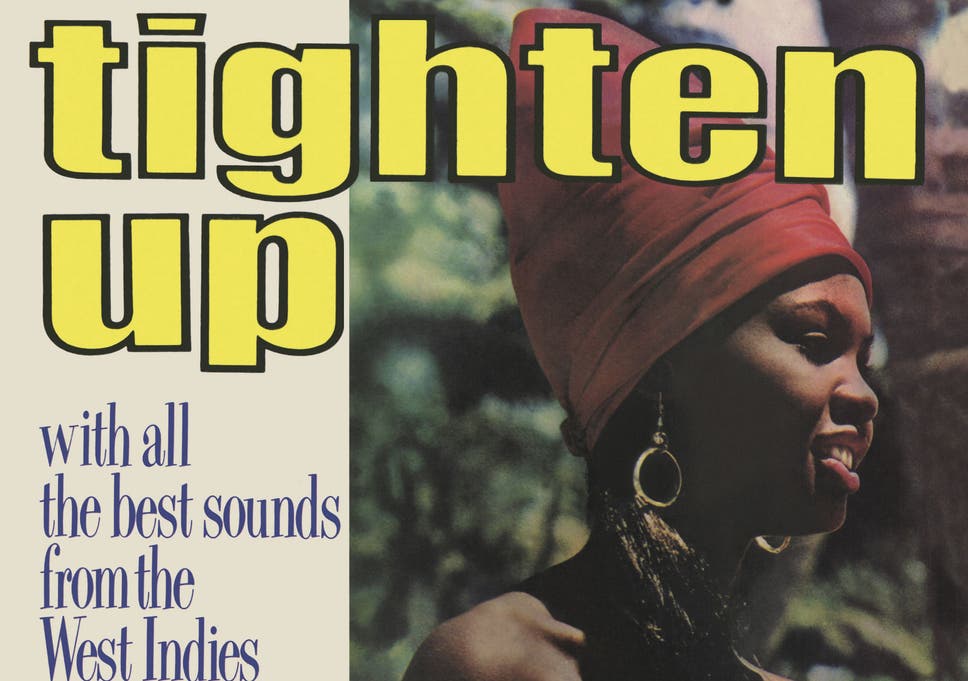

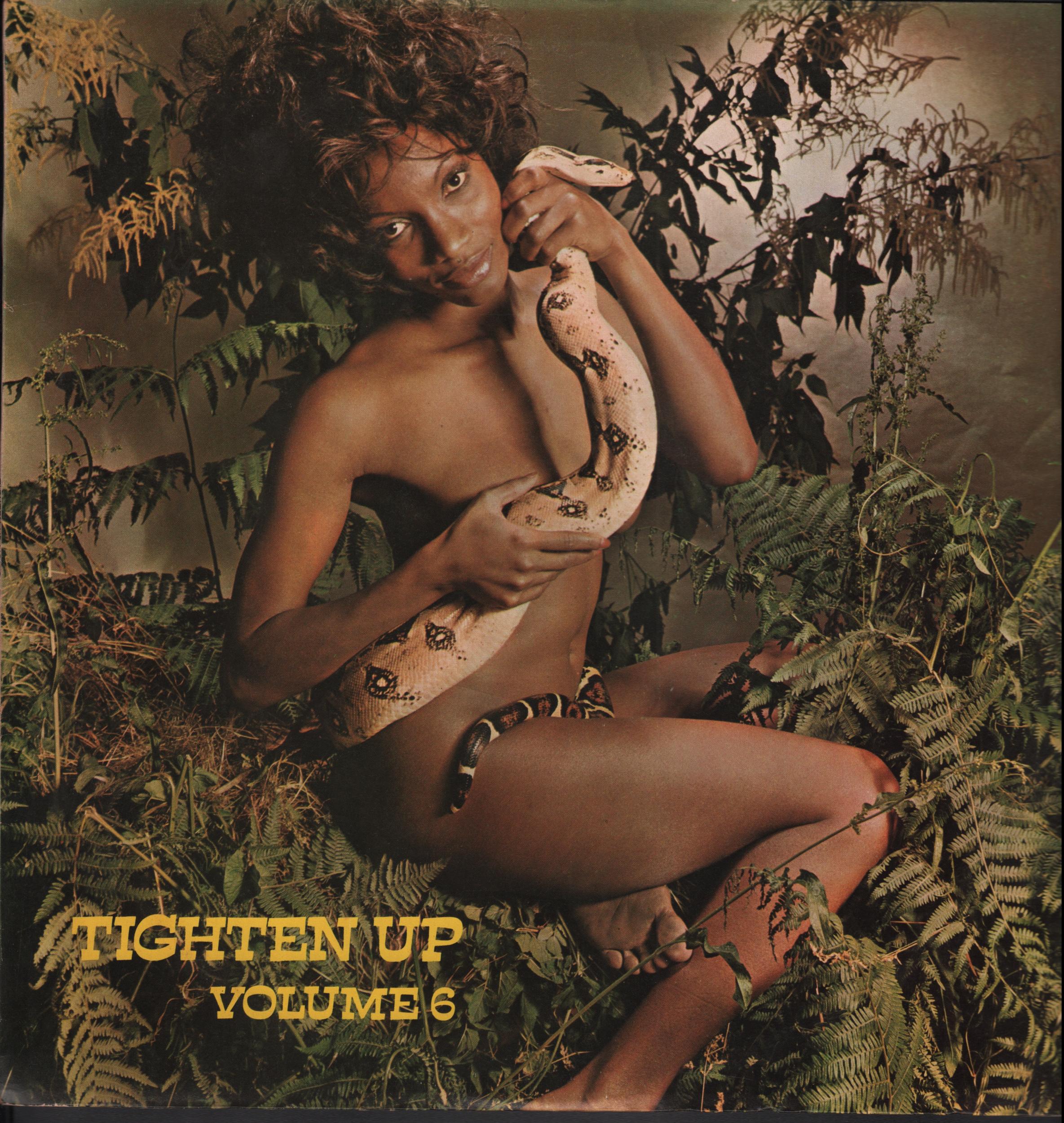

Yet with little disposable income, they were wary of punting on 7-inches. In 1969, Trojan’s answer was to embark on a series of budget compilations, titled Tighten Up, to introduce newcomers to the latest grooves and provide snapshots of a fast-moving genre. Often decorated with eye-catching images of scantily clad females, Reggae’s Now That’s What I Call Music was an immediate success, Cane-Honeysett explains.

“Tighten Up introduced reggae to the masses and a lot of those people loved the music and became skinheads as a result,” he says.

Later that year, the label’s singles finally began to breach the charts, beginning with Tony Tribe’s “Red, Red Wine”.

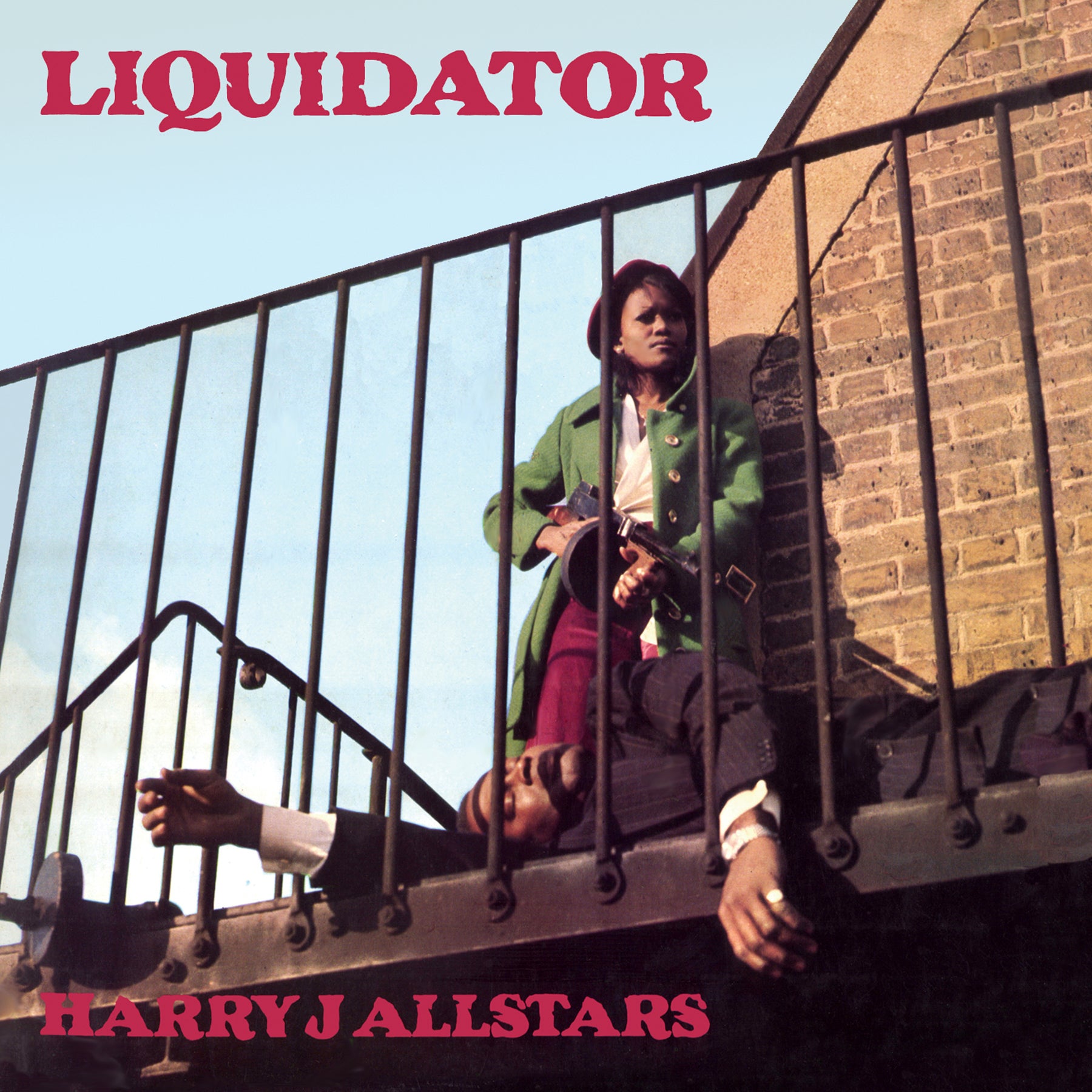

October saw a stunning coup, with placings for a quartet of key releases. Lee “Scratch” Perry made his Top 50 debut with The Upsetters’ “Return of Django”, swiftly followed by another instrumental, “The Liquidator” by Harry J Allstars, soon to be heard at football grounds around the country. The Pioneers scored with “Long Shot Kick De Bucket” and, at long last, came a hit for an artist associated with Island and Trojan for four years, Jimmy Cliff. “Wonderful World, Beautiful People” reached number six, with three others making the Top 10.

An early fan was Don Letts, a 12-year-old Brixtonian in 1968, bonding with black and white mates over this exciting new music.

“White working-class kids had long enjoyed black music, but pre-Windrush it was some kind of exotica. Now it was a second language,” he recalls. “Trojan soundtracked my early teens and ignited by lifelong love of reggae; and it was launched at the same time as Enoch Powell made his Rivers of Blood speech.”

Letts, who in the past has selected tracks for his own Trojan compilation, points to the volume and quality of music that came from the label, enjoying an unprecedented run of hits right through to the mid Seventies.

“They really represented quality Jamaican music, though it was rarely political, it was about having a good time. When they had their first number one [Dave and Ansel Collins’ “Double Barrel”, 1971], I held my head up pretty high at school.”

As well as releasing pop-orientated material under its own name, Trojan offered sub-labels as inducements to favoured Jamaican producers, among them Reid, Perry and Joe Gibbs. Meanwhile, struggling competitors were absorbed into the Trojan empire.

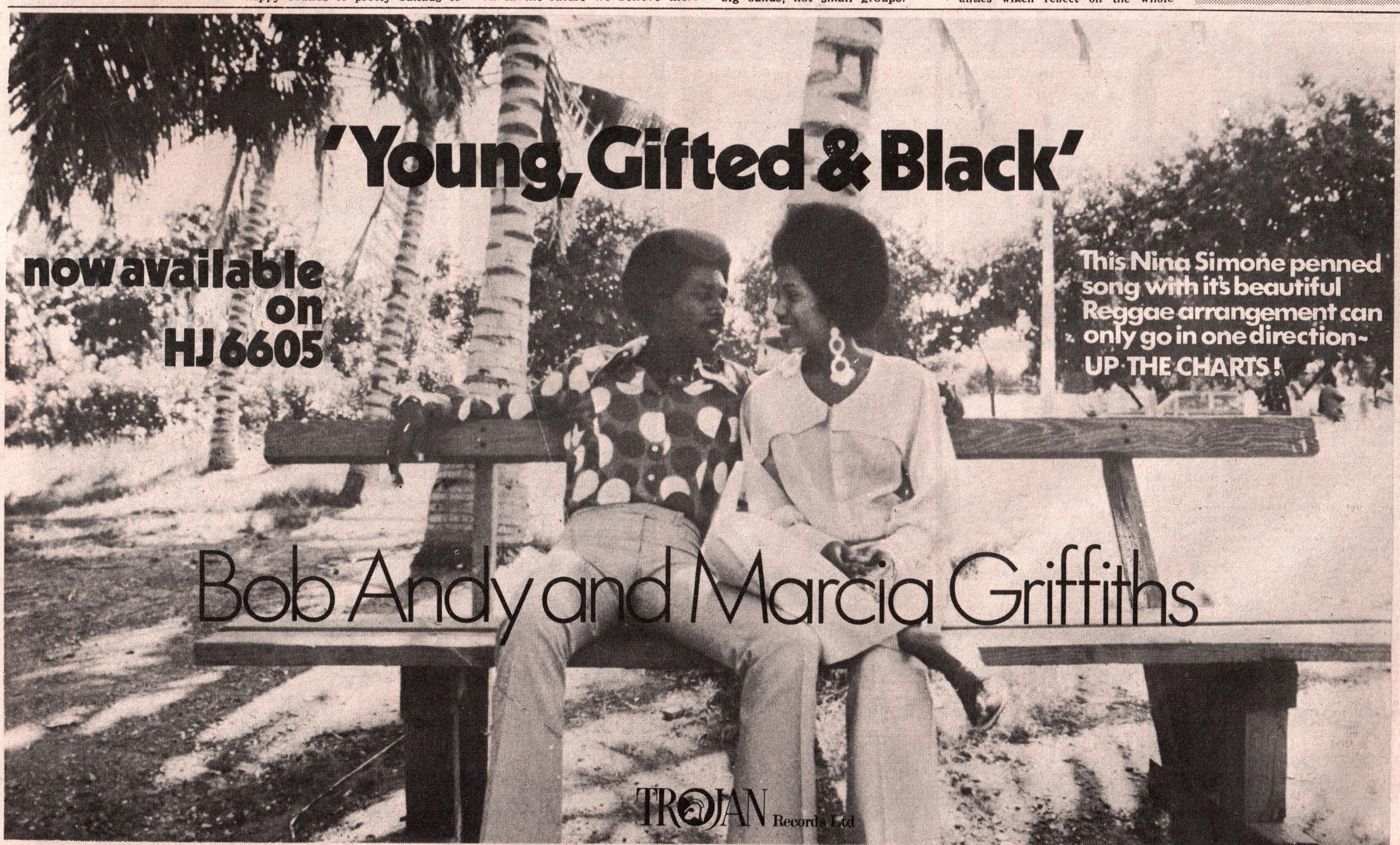

As the new decade arrived, its producers began devising a more sophisticated sound, adding strings and orchestration for a more commercial appeal, as with Bob & Marcia “Young, Gifted And Black”.

Trojan’s business model still relied on releasing as many records as possible, at its peak up to 10 a week. Yet the label missed the evolution of Jamaican music into dub’s echoing chambers and the politicised lyrics of roots reggae; nor were its managers able to really develop artists, as Island achieved later with Marley.

Its decline began in 1972 when Island pulled out, Cane-Honeysett explains: “Losing Island’s expertise and marketing nous had a big impact. Trojan was managing and producing more artists in the UK, which cost a lot of money when the skinheads were moving on.”

Three years later, the company was liquidated and the name lost momentum under the poor management of new owners Saga Records, with little interest or expertise in reggae.

Still, it didn’t stay down for long: Trojan Records’ profile was buoyed in 1979 when the Two Tone movement led by The Specials revived interest in ska. The label began to market its back catalogue for collectors, a process taken on with greater alacrity under new ownership in the mid-Eighties.

A more serious issue dating back to the original sale of Trojan was the perception among artists, especially singers, that the label had withheld funds from them. In fact, Reid’s machinations in the Sixties suggest how powerful producers had been: they held copyright, licensed tracks to UK labels and were responsible for paying vocalists, many of whom lost out on royalties.

Cane-Honeysett argues that throughout its buyouts, Trojan staff have done their best to right any wrongs by creating contracts for vocalists.

“It took a while for Trojan to claw back that respect,” following the 1975 buyout, he suggests. “Going back to the Eighties, the label has always been more proactive than it’s given credit for in terms of securing new deals, tying up old ones.”

The challenge is exacerbated by the sheer volume of the label’s catalogue, which the author estimates at between 15,000 and 20,000 tracks.

Since the mid-Noughties, Trojan has been part of much larger operations, first the ambitious Sanctuary Records, then Universal and now BMG, ensuring this 50th birthday welcomes lavish celebrations, including a film, Rudeboy: The Story of Trojan Records, which is completed and seeking distribution.

For Cane-Honeysett, and colleagues past and present, though, their lifelong obsession remains the same. “Apart from the Saga period, everyone has shared the love. People involved years ago still talk about it. Once you’ve worked there, you just don’t want to let go.”

Trojan Records’ 50th Anniversary Box Set is out 27 July. ‘The Story of Trojan Records’ by Laurence Cane-Honeysett is published by BMG Books and Eye Books, 2 August