Nearly two decades ago, I called on an old lady in Thrissur. My purpose was simple — to see face-to-face the person whose memoir I had just translated from Malayalam to English. Devaki Nilayamgode had made waves in Kerala with her book Nashtabodhangalillathe (With No Sense of Loss, 2003), a warts-and-all, insider account of the life of an Antharjanam (a Namboodiri woman). She had started writing in her 70s and was around 75 when the book was published.

Her youth had coincided with the time when the Namboodiri community, like the rest of Malabar, was transitioning from the life-sapping confines of orthodoxy to the relatively freer space of liberal values. Like other women of that time, Nilayamgode heeded the calls of social reformers, such as V. T. Bhattarthiripad, and drew inspiration from the works of M. R. Bhattathiripad. The popularity of the book was so resounding that it encouraged her to publish a slim, complementary volume three years later. It was titled Yaathra: Kaattilum Naattilum (Journey: Through Forests and Lands).

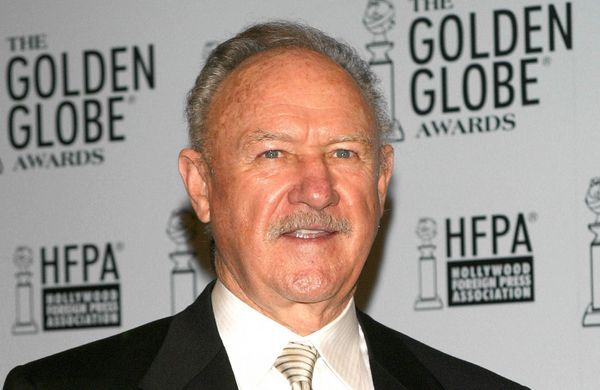

Mini Krishnan, Editor (Translations) of Oxford University Press, who would oversee the translation project of these two narratives (Yaathra was translated by Indira Menon) until it came out as Antharjanam: Memoirs of a Namboodiri Woman in 2011, had predicted that an interface with the author would do the English version a power of good. And sensing that I would gain newer insights into what Nilayamgode had left unsaid in her narrative, she spurred me on, and even mailed a typescript of my draft to Chintha Ravi, celebrated writer, film director and Left intellectual (and Nilayamgode’s son-in-law), for an informal evaluation.

The welcome was a very subdued but heartwarming one, completely in sync with the personality her reminiscences had revealed to my sensibility. Her voice was soft, like the swish of a peacock feather. But, unknown even to her, Nilayamgode’s mellow and reserved nature told me that I should scrutinise my translation in order to ensure not a single hard-sounding word had slipped into my text. Mind the tone, I told myself.

Chinta Ravi was more forthcoming in his response. Citing a tiny phrase in my translation, he wondered why I chose to deny the English readers a chance to enter the acoustic atmosphere Nilayamgode had created. He was referring to the line: “...there would be Namboodiri women, on their way to or from the Mookkuthala temple. Each had a chaperone who loudly announced their presence as they walked.” He thought I had unnecessarily subdued a vivid scene. Lesson learnt, I changed those lines to: “Each had a chaperone who led the way, shouting ‘Yaa... hey... yaa... hey...’. This version was not only truer to the original but also contained a sliver of drama I owed my readers.

As my editor had hinted, I came away humbled and nourished. Nilayamgode gave me valuable lessons in translation I respect and implement to this day — to be absolutely respectful to the tone of the text, and to train all my senses to capture the riches that even minuscule segments contain. Nilayamgode might not have been conscious of the impact she made but, like all beautiful minds, she left a lasting impression on me. Today, she has disappeared indistinguishably into the panchabhutas yet her fragrance remains. The passing away of the famous artist Namboodiri, a few days after Nilayamgode, intensifies the loss. His illustrations, rendered gratis for the entire book, at once leaven the narrative and accentuate its reality quotient.

While Antharjanam is undoubtedly a memoir, its value as a rich social document cannot be ignored. The narrative is woven out of various threads — tales handed down through generations, descriptions of the mores of the time, references to contemporary and past historical events, sketches of the prevailing agrarian economy, communitarian reforms accompanied by (nominal) women’s empowerment, political changes and the nationalist movement, shift in social sensibilities and so on — all presented against the backdrop of Nilayamgode’s gradual evolution over six decades, from a child born into a sprawling, multi-generational family in a prosperous Namboodiri illam to a matriarch, in her own right, of a nuclear family.

It is a life story that, in a beautifully restrained manner, focuses more on gains than losses, hope than regret, open skies than gilded cages, and forward movement than stasis. But the argument is so gently made that it leaves the present-day reader in a swirl of mixed feelings. The heart-rending stories of tragedies wrought by superstition, lack of scientific knowledge and ossified patriarchal cruelty trigger in us a renewed appreciation for the progress we have made.

But Antharjanam also reminds us of the treasures we have lost forever — gifted toxicologists, idealistic social leaders, the simpler joys and unhurried pace of life. Like its author, the text is mild but evocative; laconic yet nuanced; clear, still unequivocal.

The writer has translated several works from Malayalam to English.