Erykah Gatson always feels a little nervous walking into any synagogue for services that she does not regularly attend.

“I get worried that I could be seen as an intruder or otherwise, when I am there for the same purpose of Jews that don’t look like me,” Gatson tells Mic.

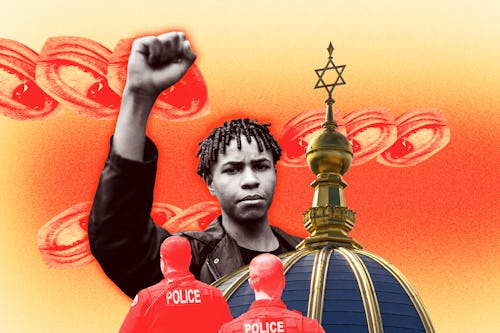

Gatson, a Black Jewish writer and activist, is often one of the only people of color at her synagogue. She says it can make her religious experience alienating — particularly as Jewish religious centers have been attacked lately. With Jews being one of the most targeted religious groups in the U.S., some Jewish houses of worship have taken to posting increased security outside their doors. The desire for protection is understandable, but for some Black Jews, police officers lingering outside their synagogues is deeply discomfiting.

“I very deeply understand the need for some sort of security at synagogue, but it does not make for a comforting experience,” Gatson says. “As a Black Jew, it feels like I have to continue to worry about not being protected by those brought in to protect the community.”

Across the country, there are people who, like Gatson, make up the often small number of Jewish people of color in their congregation and feel similarly uncomfortable. Elijah Manley, a Black Jewish man in Florida, tells Mic he often feels ostracized at his temple for being the only Black person in the room.

“I’ve attempted to go to temple to learn or get in touch with faith, but I am stared at or seem out of place,” says Manley, who is also running for a seat in Florida’s state legislature. “I feel less safe being anywhere that could be targeted by white supremacists and Nazis with guns.”

Jewish institutions have relied on police during religious attacks throughout history. During the 1950s, white supremacists targeted Jewish institutions, particularly synagogues, with bombings. Southern officials created a network of police departments across 28 cities to exchange information on any synagogue bombings. With the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting in November 2018, the hostage situation at a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, this January, and various isolated attacks — 683 anti-Jewish attacks were reported in 2020 alone, according to the U.S. Department of Justice — the community is increasingly relying on police to keep their spaces safe. The five-year anniversary of the August 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in which neo-Nazis marched in the streets yelling “Jews will not replace us,” is another stark reminder of the anti-Jewish hate that has been reawakened in recent years.

“It’s educating people about the full diversity of our Jewish community, and recognizing that there is a sizable number of Black and brown Jews in the United States.”

But during the nationwide protests against police brutality in the summer of 2020, Black Jewish activists began challenging white Jews’ ties to police in Jewish institutions. The Jewish Federation of North America, a national group lobbying and raising millions to support Jewish communities, launched a diversity, equity, and inclusion initiative after George Floyd was murdered by police in Minnesota. One of the tasks is to work with various types of security and safety programs in Jewish institutions across the country to promote equitable practices through a Jewish equity, diversity, and inclusion lens (creating the acronym JEDI), according to Nate Looney, the director of community safety and belonging at The Jewish Federation of North America.

“It’s not only educating people about the importance of understanding implicit bias,” says Looney, who is Black and Jewish. “It’s educating people about the full diversity of our Jewish community, and recognizing that there is a sizable number of Black and brown Jews in the United States.”

The rise in anti-Jewish hate has made the need for police presence in religious spaces feel more vital, but some Black Jewish people, who face racism outside of their faith, are being forced to experience the same trauma during worship.

“The harm is caused when Black and brown people come in and they’re not coded as Jewish and they are treated as if they are somehow strangers,” says Sandra Lawson, a Black female rabbi based in North Carolina. "[They] are treated as if they do not belong by security and white members of the community, even though the people who continue to try to harm Jews in the United States overwhelmingly do not look like me.” Lawson works remotely as the director of racial diversity, equity, and inclusion for Reconstructing Judaism — the fourth largest denomination of Judaism, which trains rabbis and cultivates spaces globally for Reconstructionist Jews.

Shais Rishon, a Black Orthodox Jewish man and former rabbi of Kehilat Ir Chadash in New York City, echoes Lawson’s sentiment. He says he’s been greeted in the past by congregants who assumed he didn’t also belong to the synagogue. Rishon recalls specific experiences like these at past Erev Shabbat services, which are Friday evening services that precede Saturday Shabbat service. He thinks it’s because he doesn’t look like the typical white Jew, adding that the interactions reeked of entitlement.

“Sometimes those [white] people are the ones who call the police or get security from the front because they have the assumption that the police are going to protect them,” Rishon tells Mic.

The problem here is twofold: firstly, that non-white Jews are not seen as belonging in their own spaces of worship, and secondly, that the response to that wrong perception is often to call in extra security, which can make non-white people feel unsafe. The result is that some Black and brown Jews may choose to practice at home to avoid dealing with these microaggressions — Manley says he falls into this category — which protects their safety in worship, but adds to the public perception of Jews as mostly white.

Maxim Samson, who studies geographies of religious identities at DePaul University in Chicago, says it's hard to know how policing in Jewish institutions is affecting Jewish people of color on a larger scale for two reasons: Researchers have paid the issue little attention, and some Jews of color are hesitant to speak out about their experiences in the synagogue. But the tension is real.

Safety is clearly top of mind for Benzoin Singer, a rabbi at Chabad Lauderdale-By-The-Sea in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. His synagogue has hired private officers and private security to stand guard during services, especially during busy times like the high holidays of Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. “We have witnessed these attacks too many times,” he says. “Take a look at Pittsburgh and so many other places. We can’t take chances. It’s important we can practice our religion and proudly come to synagogue to pray. We have to know we can do that without fearing for our lives and for our safety.”

It’s a tough dynamic to balance for rabbis, who feel a responsibility to keep worshipers safe, but also may not want to give into the fear anti-Jewish hate was designed to create. “The last thing we want is for people to go into hiding, to stop practicing Judaism because of security concerns,” Singer says.

“Sometimes the best security, you don’t even know it’s there.”

At the same time, Black Jewish people are also struggling with the dynamic of being wary of police interactions while at synagogue and also fearing violent persecution. And then there are the more overt instances of discrimination. While Lawson herself has never been barred from entering synagogue by security, she says she’s heard it happen to other Black Jews, including several friends of hers.

Looney describes a similar feeling of being singled out. “It's the way in which security interacts with you,” he says. “If I see security sizing me up in a certain way, that's going to put me in a state of alert, rather than if someone is just casually engaging with me or greeting me in a welcoming way.”

Part of Looney’s work with the Jewish Federations of North America’s JEDI initiative includes developing multiple levels of security that don’t involve visible armed police or guards. This could mean having a designated person on the lookout for concerning behaviors, or installing metal detectors and real-time security cameras that are connected to local law enforcement to ensure a prompt response if a situation does arise. “Sometimes the best security, you don’t even know it’s there,” he says.

Lawson acknowledges, though, that these less traditional security tactics may leave white Jews feeling more exposed. “Many people who are white in the Jewish community are concerned that new conversations around security will mean that ‘I as a white person am less safe, my family is less safe,’” she says. But she points out that making a larger, more inclusive group of people feel protected is, in fact, an expansion of security. “What I want people to understand is by creating a better security plan that includes a diversity, equity, and inclusion lens, you’re creating a security plan that actually makes everybody safe. Not just one group of people.”

Getting that message across requires something many of the Black Jewish community leaders Mic spoke to agreed on: education. Maybe it should be obvious that the safety and peace of mind of non-white Jews matters just as much as white Jews, but several of the people Mic spoke with acknowledged there may be a need for some explicit teaching.

“I think educating people on antisemitism can go a long way, but I also believe that educating people in an intersectional way — on the struggles of all people — will make people more understanding and less likely to alienate others in their community,” says Manley, the Black Jewish man running for local politics in Florida. “I would like to see temple become a more welcoming place for non-white people and people of color.”

After all, he says, “at the end of the day, we all have the same oppressors.”

This article was produced in partnership with Just Media, a national hub supporting young writers covering justice issues.