This feature originally appeared in issue 338 of Total Film. Subscribe to Total Film here to never miss an issue.

If genius is patience, as Sir Isaac Newton once attested, Total Film witnesses genius in abundance on the dub stage at the Warner Bros. lot, Burbank, California, on an uncharacteristically rainy day in January. It’s in here that the sound mix is being finessed on Christopher Nolan’s new film, Oppenheimer – the true story of a tortured genius whose impact on history is hard to overstate.

This room is where Nolan and his producing partner and wife, Emma Thomas, have mixed their films as far back as 2006’s The Prestige; even though Oppenheimer is being distributed by Universal, these facilities are often hired out between studios (Nolan’s Memento was actually mixed on the Universal lot).

This feature first appeared in Total Film magazine - Subscribe here to save on the cover price, get exclusive covers, and have it delivered to your door or device every month.

Dub stage 1 boasts an enormous screen, in front of which sits a bank of desks 30ft wide, occupied by at least half a dozen people sitting at monitors (many of whom are long-term Nolan collaborators). TF slinks into the back of the room and sinks into a black sofa, as Nolan – alongside editor Jennifer Lame (Tenet) – leads the team through some painstakingly precise soundtrack tweaks over a couple of minutes’ worth of (frankly stunning-looking) footage from Oppenheimer.

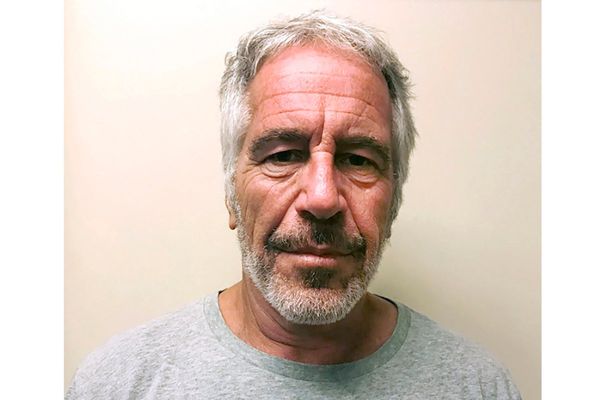

The film is the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American physicist considered to be the 'father' of the atomic bomb, and, in Nolan’s words, "the most important person who ever lived". A scientific genius who oversaw the creation of the world’s most destructive weapon, Oppenheimer would later lobby against nuclear proliferation, and found his loyalty scrutinised on the public stage when he faced a security hearing for Communist Party connections.

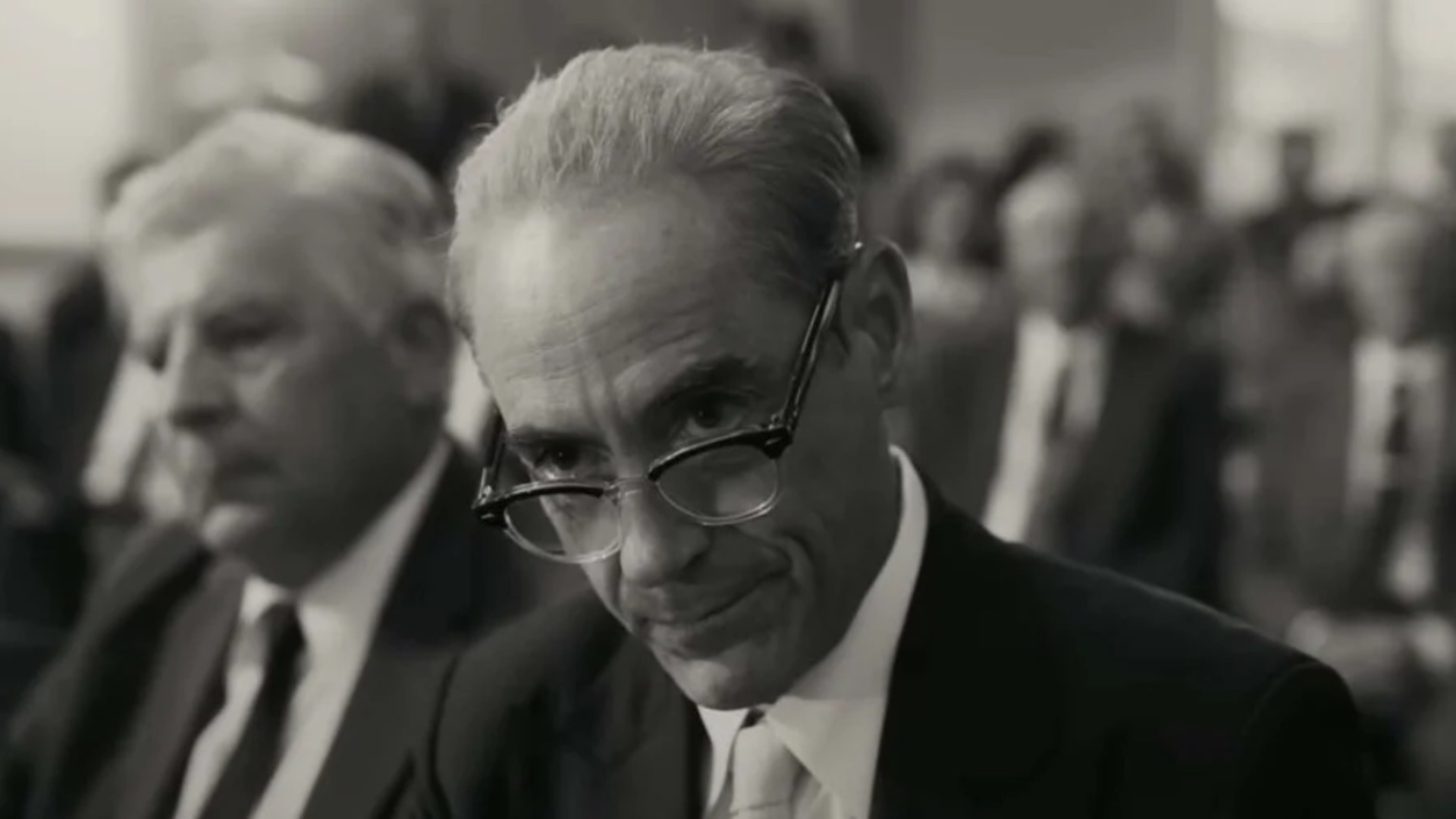

Voices are hushed, but not whispers, and the atmosphere is relaxed, congenial, as the sound mix is finely tuned. The footage includes a blackand-white trial scene in which Robert Downey Jr.’s Lewis Strauss asks questions about an FBI file on Oppenheimer. We then cut to a scene featuring a young Oppie (as he was known to his friends) at Berkeley. Cillian Murphy – a frequent and valuable supporting player for Nolan – steps up to the lead role here.

"Roll a little off the top in the last one second," suggests Nolan, as the team fine-tooth-comb their way through the sound mix, getting the level of Ludwig Göransson’s sublime-sounding score just right. The process has its own language ("The tail is good, maybe we just soften the attack?"), as the minutes of footage play over and over, and the mix is chiselled to perfection. Even in this brief glimpse, the ambition of Oppenheimer is laid bare. The time-hopping narrative. Murphy’s decades-spanning performance. An expansive supporting cast, including a formidable Downey Jr. An impressive glimpse at some practical special effects that represent the whirring, whizzing microscopic components of the science Oppenheimer pioneers. The rumbling sound design playing under some of these trippy visuals shakes the room.

Throughout proceedings, Nolan strolls to different monitors. "Try it, we can always go back," seems to be a mantra for these sessions. The level of the score is adjusted. A minor ADR tweak clarifies the pronunciation of a name. When something’s deemed "Perfect", it’s recorded, and the team moves on. For all the precision, the mood is light. "Whatever that was we should not do," jokes Nolan after one run-through.

When the team breaks for lunch, TF joins Nolan in a lounge off to the side of the stage. "We’re balancing the sound effects, the dialogue, and the music, and polishing the film, basically," he explains. The film is – in Nolan’s words – "kissing three hours". That’s a lot of material in need of this attention. By this point, he’s watched the film "hundreds and hundreds" of times.

Nuclear frisson

A new Christopher Nolan film comes with its own set of expectations. While his films are defiantly original in an era of IP-led blockbusters, Nolan trademarks include daring narrative structures, a commitment to practical effects on a huge scale, large-format celluloid photography (Nolan drove the IMAX boom in feature filmmaking) and pioneering sound design. To date, Oppenheimer is the first Nolan feature that could be classified as a biopic (although he scripted an unmade Howard Hughes project that was sidelined by Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator). Dunkirk, while set during the real evacuation in World War Two, doesn’t feature characters based on specific people, and keeps the larger political context in the background, prioritising an against-theclock survival story. Oppenheimer tells the story of a man who changed the course of history, even if his life and experiences tend to be remembered in broad strokes rather than granular detail.

"I’ve always been drawn to interesting protagonists – protagonists who have ambiguity to them," says Nolan, dressed in his unofficial uniform of dark blazer, tweed waistcoat and pale-blue linen scarf, sipping tea from a large black mug. "I think of any character I’ve dealt with, Oppenheimer is by far the most ambiguous and paradoxical. Which, given that I’ve made three Batman films, is saying a lot."

In fact, it’s the real-life nature of Oppenheimer’s story that enabled Nolan to push this preoccupation to an extreme. "There are no easy answers to any aspect of the story," continues Nolan. "I think, in a way, he’s the extreme of the type of protagonist I’ve been interested in over the years."

What is it about Oppenheimer that makes him so contradictory and ambiguous, then? He’s been a long-term interest of Nolan’s. "Certainly, I would say, when I first read the reference to Oppenheimer in Tenet, I was not surprised to see it there, because it has always been a subject that has fascinated Chris," says Thomas when we catch up properly later. That reference being Priya (Dimple Kapadia) namechecking Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project, and the defining moment where they tested the bomb, despite believing there was a small risk that the resulting chain reaction would ignite the atmosphere. "I kind of like the fact that he gives us clues to the next one in his films. I think he’s long been intrigued by Oppenheimer as a historical figure, but also by the story of how the Manhattan Project came to be, and what happened to Oppenheimer afterwards."

Extreme contradictions permeate Oppenheimer’s life and work. The book on which the film is based – Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s American Prometheus from 2005 - draws on Greek mythology for its title (a parallel that Scientific Monthly drew as far back as 1945). The legend has it that Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to humankind, and was punished for his actions by eternal torment.

Oppenheimer and his Manhattan Project collaborators would gift/curse humanity with the ultimate weapon, brought into being during the crucible of World War Two at Los Alamos National Laboratory, a secret facility devoted to creating a war-ending "gadget". To stretch the Greek mythology analogy further, the invention of the atomic bomb opened a Pandora’s box that would never again be closed.

Besides the extreme contradiction at the heart of his work, Oppenheimer was a man of multitudes. A scientific genius whose ability would change the world, he was also an aesthete and poetry lover. He could be socially awkward, but was also an adulterous womaniser. Brilliant, but naive. And despite his scientific gifts, he was deeply spiritual, learning Sanskrit and taking inspiration from the sacred Hindu text the Bhagavad Gita. When the weapon was detonated during the Trinity Test, Oppenheimer famously uttered a line from that text: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

Power Trip

This title role represents a considerable demand on an actor. Nolan says that he writes screenplays without casting in mind, believing it can be limiting. But here, Cillian Murphy – who has supporting previous on five Nolan films: Inception, Dunkirk and the Dark Knight trilogy – steps into the lead.

"I think any actor in the world would want to work with Chris Nolan, no matter what size the part," Murphy tells TF from his Dublin home. "And then, our working relationship has developed over 20 years now. I feel really, really lucky that it has. And, yeah, for sure, I was always secretly hoping that he might find a big part for me. And then he just called me in September ’21. He just called me out of the blue, and said, “Here’s the script, and here’s the part. I’d love for you to play it." That’s the way he operates,’ Murphy laughs. "It was huge. And it’s been a while to quite fathom the size of the part, and the size of the possibility. I had a long time to prep."

"He’s playing a massive swathe of the guy’s life," says Nolan, "and that presents challenges. I mean, yes, there are physical challenges with that. But more than that, the psychological challenge is trying to absorb an entire life experience of somebody else. Not just a moment in time, but whole periods of his life and to show that to the audience, and to allow the audience to feel that with him. It’s a big challenge I’ve set him. He stepped up to it far beyond what I would have imagined was possible, just in taking you into his head and his experience."

Murphy only had a surface awareness of Oppenheimer before throwing himself into the project. "I think I had kind of Wikipedia-level of knowledge of Oppenheimer, like most people," he admits. "So then it was… Well, it was just starting from scratch, really. Chris guided me through that. You can only do it one bite at a time. You have to go slowly. And thankfully we had time." Murphy says that he was never going to do an impersonation of the real Oppenheimer, "but it was very helpful to me to find that silhouette, to be able to embrace the iconography of him, which was the hat and the pipe, and certainly the cut of his suits, and to try to find a physical shape that would make that as iconic as [he was in real life]. Because he was very conscious about that. It wasn’t by accident. He chose that look for himself."

Oppenheimer also has a very distinct accent that was well-documented in recordings, though Murphy’s hesitant to delve too deeply into the details of his preparation for the role. "I’m very much a fan of going into the film without any sort of notions of actors’ twaddle beforehand," he laughs.

As for why Murphy seemed right for the part, Nolan talks of his "intense eyes" (which he has been putting to good use for Nolan since Batman Begins) as a jumping-off point. "But in truth, there are just not that many actors that you could say, on a first-person approach, 'Yeah, we’re going to be this guy for three hours.' You’re making a demand of an actor that very few actors in the history of film can rise to. I will say that even with that confidence in him, he was continually surprising me on set every day. And when we got into the edit suite and were putting the performance together, and seeing the truth of it, I was absolutely blown away."

Ensemble assemble

The focus on subjective experience is another aspect of Oppenheimer that places it firmly in Nolan’s oeuvre (and the mix of black-and-white and colour photography harks back to 2000’s Memento). "I wrote the script in the first person, which I’d never done before," he says. "I don’t know if anyone has ever done that, or if that’s a thing people do or not… The film is objective and subjective. The colour scenes are subjective; the black-and-white scenes are objective. I wrote the colour scenes from the first person. So for an actor reading that, in some ways, I think it’d be quite daunting."

But despite Robert Oppenheimer being at the story’s centre, he’s operating in a colossal moment of history, which has led Nolan to secure a frankly staggering supporting cast. It’s another element of the film that makes it feel more ‘event picture’ than your standard historical biopic.

Alongside Murphy is Emily Blunt, who plays Oppenheimer’s wife Katherine, known as Kitty. Blunt, a Nolan newcomer, describes the process of landing the role to TF. "I think once he’s decided to meet you, that means that that’s good news, because he’s so specific," she reveals. "But I read [the script] in his house, and it was absolutely heart-pounding. And honestly, I would have done it if it was one scene."

When TF asks if it was a challenge to take in the script in one reading, given that it’s a three-hour, era-spanning epic grappling with some of the biggest scientific breakthroughs and knottiest themes of our time, Blunt says, "No, because the script was so emotional, and it reads like a thriller. It’s almost like he’s a Trojan-Horsed a biopic into a thriller. It’s really pulse-racing, the whole thing. I was just completely arrested by the story, the portrait of this man, and, I guess, the trauma of a brain like that."

Even though the events the film covers are documented in great detail in Bird and Sherwin’s book (and countless other historical documents), the cast are hesitant about going into too much detail before cinema audiences have had a chance to see the film.

"But for anyone who knows anything about Kitty Oppenheimer, she was a pretty monumental presence in his life as a confidante, and as a real scientific brain herself," Blunt reveals. "But she was, you know, a very big personality." She laughs. "Not necessarily one to conform to a housewife ideal of the time. A very big character."

Murphy and Blunt previously worked together on A Quiet Place Part 2. "I think that sometimes, you get stuff for free," says Murphy. "If actors have worked together, and it’s gone well, and they’re friends, something happens on screen. And that journey that these characters in Oppenheimer have to make is kind of an extraordinary one. I think it benefits in two ways, because Emily is one of the greatest actors around, and then we have this history already."

The cast is also filled out with the likes of the aforementioned Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss, chairman of the US Atomic Energy Commission, who was a dominant opponent of Oppenheimer’s during his McCarthy-era trial; Matt Damon as Leslie Groves, a top army official who served as director of the Manhattan Project; and Florence Pugh as Jean Tatlock, a psychiatrist and left-leaning writer who had a relationship with Oppenheimer that began before he was married to Kitty.

But that’s just the scratching the surface of a deep bench of supporting players that includes A-listers, Oscarwinners and character actors. To name a few familiar faces, there’s Rami Malek, Kenneth Branagh, Benny Safdie, Dane DeHaan and Alden Ehrenreich. Josh Hartnett also makes his Nolan debut, having previously met him to discuss earlier projects that did not work out (most famously Batman Begins).

"With the number of giant movie stars on this film, you would expect that lots of people’s egos would come into play," Hartnett tells TF. "You don’t see that on Christopher Nolan’s films, I think, because everybody knows that they’re there for a very specific reason, and they’re there to support the film and the filmmaker. So the egos are sort of checked at the door, and therefore you’re allowed to be much more sort of natural, and to be yourself, on set and on off. And when you’re shooting in the middle of nowhere, you get to know people fairly well."

Hartnett plays Ernest Lawrence, a nuclear physicist who did essential work on the Manhattan Project. "I knew very little about him before taking on this role, and it’s surprising to me that someone who was so instrumental in the choices that were made surrounding both the Manhattan Project and also the Rad Lab [MIT Radiation Laboratory] and physics within the US generally… for me to have very little familiarity with him as a historical figure was surprising."

Also hesitant to delve into the character’s portrayal at this stage, Hartnett does say that Oppie and Lawrence were 'best friends'. "Lawrence named one of his kids after Oppenheimer, and they worked together very closely for a long time, and ended up being close colleagues," he says.

Thomas says that they got their regular casting director, John Papsidera (Memento, the Dark Knight trilogy and more), on board extremely early in the process: "when we were taking the project out to studios, and we wanted to be able to say to them, 'These are the sort of actors that we’re thinking about,'" says Thomas. "We knew from the beginning that we wanted to try and assemble a really, really fantastic cast."

For Nolan, it represents something of a throwback to a previous era of movie-making. "When I was casting Batman Begins, my pitch to the studio was, 'I want to do what Dick Donner did in the 1978 Superman.' I remember as a kid just seeing these big actors – Glenn Ford… Marlon Brando… Gene Hackman… this incredible cast. It made the film feel so big… That was something that went out of pop filmmaking in some ways. With Batman Begins, we really tried to bring it back. So whilst I’ve always tried to cast the best possible actors, there’s a reason that a lot of movie stars are where they are. It’s, for me, a really fun and challenging combination of an incredible ensemble, but the film is so focused on one man’s experience, and one man’s view of the world."

Practical magic

The casting is just one aspect of the film that’s resolutely old-school. Nolan has long been a champion of celluloid, and pioneered the use of large-format IMAX film in features, from The Dark Knight onwards. For Oppenheimer’s black-and-white sequences, analogue black-and-white IMAX film was used for the first time.

Nolan has always favoured practical effects where possible, and that tradition continues with Oppenheimer. Where others might opt to recreate the Trinity Test (the testing of the atomic bomb in July 1945) entirely with CGI, Nolan took a different tack, beginning discussions early with special-effects supervisor Scott R. Fisher and visual-effects supervisor Andrew Jackson. "The distinction is: special effects are things you actually do on the floor, and visual effects are things you do in post-production, broadly speaking," says Nolan.

"[Jackson has] got a background in both. So he was able to go to Scott Fisher, who was running special effects on the film, and talk about my initial impulse, which was: 'Yes, we’ve got to represent the Trinity Test, but we also have to represent these images, these things in Oppenheimer’s head; his ability to look into matter, and see and feel energy there.' The most obvious thing to do would be to do them all with computer graphics. But I knew that that was not going to achieve the sort of tactile, ragged, real nature of what I wanted. And so the goal was – and in the end, we have achieved it - the goal was to have everything that appears in the film be photographed. And have the computer used for what it’s best for, which is compositing, and putting ideas together; taking out things you don’t want; putting layers of things together."

As you can glimpse in the most recent trailer, Nolan’s taste for scale also comes into effect in the recreation of the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. While some interiors were shot on the real location, the area surrounding Los Alamos is now heavily modernised to accommodate tourist trade. The decision was made to build the exterior sets on a mesa in New Mexico, on a vast area of desert with no other structures around. "I was really pleased with the combination of being able to build what it would have looked like in 1942, but also being in the real places where we could have the history of it," says Nolan. "That just felt important for the project."

"There was a lot of challenge in terms of the environments we were in," says Thomas. "When we were shooting the Trinity Test, we were out in the desert, and there was sand, and there was wind. We were making rain. It was a lot."

"That was completely transporting, being there," says Blunt. "When we first drove to Los Alamos, I was like, 'This feels like old-school Hollywood filmmaking,' like you see in those old-school, black-and-white on-set photographs. It’s just so transporting when you get to work practically on a set that is textured, and you can touch. The whole experience feels tactile and real and accessible."

New world order

The danger of the power that Oppenheimer and his collaborators unleashed has never gone away, but the film’s themes – and Oppie’s turmoil – might now feel more relevant than ever, as the threat of nuclear war has been brought back to the forefront of the public consciousness in recent times.

"I was talking to one of my kids about what I was writing early on, and their response was, 'Are people that interested in that aspect? Are they that interested in nuclear weapons right now?'" recalls Nolan. "Which, right now, seems inconceivable that anyone would have said that. But the shift has been profound. Nuclear weapons are one of those things – one of those existential threats – that the human race faces that we choose to worry about at times, and at other times we choose to worry about other things. I think right now, people are very, very aware of it, and thinking about it a lot, with developments in Ukraine, obviously. But it’s something that, from Hiroshima on, has never gone anywhere as a threat."

"I think 100% it does [speak to the present day]," asserts Murphy. "It’s incredibly relevant, I think."

"I think it was surreal that that was all starting in Russia and Ukraine when we were filming," says Blunt. "It was surreal, and obviously unexpected by Chris and Emma. But, yes, very timely."

Timely subject matter. A complicated, paradoxical protagonist. A gold-standard cast. Handcrafted effects. Epic scale. You could easily adapt the cliché to say that it’s only really Nolan who makes them like this any more. Nolan is aware that it’s rare for a historical biopic to be made on this scale.

"The awareness comes in when you start talking to the studio about: 'What are the precedents?'" says Nolan. "And you have to go back as far as something like JFK, which was an event: a big movie and a big, big experience for people."

As for how the cast see what makes this historical biopic essentially Nolanesque, Murphy says, "There are elements of thriller in it, and it has that epic quality. You can never, ever predict what way a Christopher Nolan film is going to go. And he does it again on this, but I think on such a huge canvas, and with these huge themes. It’s mindblowing. Everyone in it is astonishing, and he’s done something truly special."

"It’s obviously not going to be a straight biographical piece in the way that we’ve seen any other biographical movie being made," says Hartnett.

"I just wouldn’t call this movie a biopic," says Blunt. "This is a pulse racing thriller – a big event movie. It’s an overwhelming experience. I felt like my bones would shatter watching it."

Pondering Oppenheimer’s rarefied space on the current movie landscape, as a serious heavy-hitting drama also offering spectacle in spades, Nolan considers, "I think more and more in cinema, there’s been a fragmentation of entertainment from drama, or serious drama as opposed to frivolous entertainment. There’s the danger with Hollywood filmmaking that those things get too far apart. But there’s always been that ebb and flow, over the 100 years of Hollywood movie culture."

Soon Oppenheimer will put that theory to the test when this unique biopic lands during the height of blockbuster season.

"You hope to catch the right moment in time, and that’s in the hands of the movie gods," says Nolan. "But there should never be a distinction between these things. When you look at Oppenheimer’s experience, he’s dealing with some of the most tense and paradoxical scenarios that are far beyond anything you can put into fiction."

Oppenheimer is out now on Universal 4K UHD, Blu-ray and DVD.

For more on the end of year, check out our guides to the best films of 2023 and the best TV shows of 2023.