When the results of the Conservative leadership race are announced next week, the UK’s new prime minister will be facing a formidable set of challenges. There is the worst cost of living crisis in 50 years, a war in Europe, an antagonistic relationship with the EU and divisions within the Conservative party itself. The public is sceptical about the government’s ability to solve any of these issues with many switching to Labour in the polls since December of last year.

Given this array of problems, presumed next prime minister Liz Truss’s focus on tax cuts as the solution to rapidly growing inflation looks very odd. At a time when the pound is rapidly falling in currency markets and Citi bank is forecasting an inflation rate of 18% in 2023, putting tax rebates into people’s pockets runs the risk of making inflation worse.

There is a strategy behind Truss’s approach, which makes sense if we look closely. There are votes to be won by focusing on taxes – but these are among Conservative party members, not the general public.

Looking at the public first, the issue of taxation does not appear among any of the top nine issues voters are prioritising at the moment. Not surprisingly, this list is dominated by the economy and healthcare. On the other hand, if people get help from the government to pay their fuel bills, it could very well move up the agenda and give the new prime minister a boost. Just look at how popular the pandemic furlough scheme made Truss’s leadership rival Rishi Sunak.

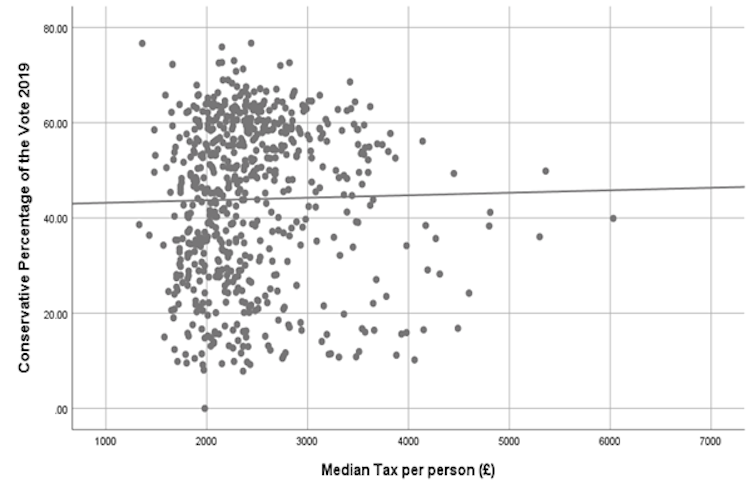

To understand the effect of tax cuts on voting, we can look directly at the relationship between tax payments and voting in the 2019 general election. A relatively obscure government publication provides data on the median tax burden in each of the 632 parliamentary constituencies in Britain at the time of the election.

The chart below, using data from this publication, shows the relationship between the median tax paid per person in each constituency, and the Conservative vote share in that election. The median tax paid in Britain was just under £2,500 at the time of the election.

The Conservative party has traditionally sought to develop its reputation as a tax-cutting party. Truss is continuing this tradition, even though tax rates are very high at the moment. Given this, we might expect constituencies that pay high taxes to be more Conservative than constituencies that pay much less.

Yet that is not what we see, since the trendline is flat – indicating that there is no relationship between support for the Conservative party and taxes paid by the typical voter. In other words, high-tax constituencies are no more likely to vote Conservative than they are to vote for another party.

Winning over party members

So what’s driving Truss’s big emphasis on tax cuts? This is a sensible strategy given that the Conservative party membership is rather old. A recent book on party membership in Britain by political scientist Tim Bale and colleagues showed that 40% of the party’s membership in 2015 was over 65.

As the chart below shows, there is an association between median pensioner incomes and voting Conservative in the election. As the typical pensioner income rises in a constituency, it is more likely to vote Conservative. The association is not very strong, but it is enough for Truss to focus on when appealing to the Tory base, who are choosing between her and Sunak to lead the party.

However, this focus could change once she is safely ensconced in Downing Street. The wider public is not interested in tax cuts and so this policy will probably rapidly fade into the background. Truss is likely to make an immediate gesture by cutting the proposed increases in national insurance rates, and then U-turn to focus on handing out cash to businesses and individuals as a matter of urgency. A failure to deal rapidly with the most salient issue in the public’s mind – the cost of living crisis – will damage her premiership from the start. This means she will essentially adopt Rishi Sunak’s strategy.

That said, she will still have to square the circle of dealing with financial markets. Continuing reliance on borrowing to fund cash handouts risks triggering a sterling crisis and capital flight – a sudden exodus of money from the country. A collapse in the value of the pound would make imports more expensive, accelerating inflation. Similarly, capital flight would make it harder for the government to borrow in order to fund tax cuts. The support of the party membership is not enough to shore up the position of the next prime minister, who will face a delicate balancing act in the run-up to the next election.

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.