(Editor’s note: This story originally published on Nov. 12, 2018.)

To those who bought the pay-per-view and took the ride on Nov. 12, 1993, it must have seemed like a wild gamble. Here was this brand new event, the Ultimate Fighting Championship, which claimed that it would deliver “no rules” fights between a hodgepodge of various martial arts masters until only one champion remained.

Also the fights would take place in an eight-sided cage, and football great Jim Brown would be there for some reason, so why not call up your cable company (pretty much the only way to order a pay-per-view event back then) and take your chances?

Still, savvy viewers must have had questions. At a time when most viewers had to choose between boxing and WWF pro wrestling as their only pay-per-view options in the combat sports realm, what were the odds that this would be a legitimate contest? And if it did mean to deliver exactly what it promised – trained martial artists beating each other in a cage until someone quit or lost consciousness – would it even be allowed on TV?

But then the time came and there it was, a broadcast from the McNichols Sports Arena in Denver that opened with karate champ Bill “Superfoot” Wallace incorrectly identifying it as the Ultimate Fighting Challenge – right before he burped on live TV.

The fact that they’d even made it to fight night was a relief to the event’s organizers. As explained in the excellent 30 for 30 podcast, “No Rules – The Birth of the UFC,” a disagreement at the rules meeting threatened to derail the entire event. According to several sources, it was only when sumo wrestler Teila Tuli signed his agreement and informed his colleagues that he “came to party” that the other fighters fell in line.

Tuli was the first man to make the walk on the broadcast that night, facing Dutch savate champion Gerard Gordeau in the opening round. Gordeau had reportedly whiled away the time backstage by smoking cigarettes and casting menacing stares at his fellow fighters. When he got his chance in the cage against the 420-pound Tuli, it took him just 26 seconds to sidestep Tuli’s bull rush, topple him to the mat, and then kick him directly in the mouth.

The commentators later joked about Tuli’s tooth flying out of the cage and landing somewhere under the broadcast table. What they didn’t realize until later was that another one of his teeth was embedded in Gordeau’s foot, where it would stay until he returned home to the Netherlands and got it removed.

The swift, violent end to the fight was something of a wake-up call. For one, it demonstrated just how serious these fights could get, and just how quickly someone could get hurt. It was also something of a shocking visual. A large man being kicked in the face as he sat on the ground? That wasn’t the kind of thing you saw every day.

Then there was the confusion after the kick. The bout was stopped almost immediately, but at first it appeared as though Tuli might get a quick check from the doctor and be allowed to continue. But as modern MMA fans know, that’s not how it works. Once you stop a bout in a moment like that, you’ve irrevocably changed it.

This is how Tuli’s night ended early, and how the UFC’s first tournament bout ended with a protested stoppage.

If fighters were shook up by seeing the level of human carnage possible in this form of fighting, they didn’t show it. In the next bout, Zane Frazier started fast against Kevin Rosier, battering him against the fence before running out of gas in the thin Denver air and eventually collapsing on the mat, earning himself a couple head stomps before his corner finally threw the towel.

Next came Royce Gracie, the chosen representative of the family that played an instrumental role in putting the event together. Royce was far from the most ferocious member of the Gracie clan, which was kind of the point. One of the goals of this event was to showcase the power of Gracie jiu-jitsu as a martial arts discipline. If the family had chosen Rickson Gracie, a pitbull of a man with a physique seemingly carved out of marble, viewers may have attributed his success to athleticism and other natural gifts rather than the art form itself.

Royce, on the other hand, was skinny and shaggy-headed, looking more like a surf bum than a world champion fighter. If he could stand alone among this tournament of monstrous men, the thinking went, it would really prove something.

Gracie didn’t exactly face the toughest test in the opening round. Art Jimmerson, a mid-level boxer who chose to wear one glove on his lead hand, ostensibly in order to leave the other free for grabbing and grappling, clearly did not know what he was in for. After being taken down and then easily mounted by Gracie, he tapped out before he could even be placed in a submission hold. The ground game seemed to be just that foreign to him.

The biggest potential challenge to Gracie came in the form of Ken Shamrock, a heavily muscled and intensely angry man who by then had already begun making a name for himself on the mixed rules fighting scene in Japan. Like Gracie, Shamrock knew a thing or two about submissions. As he demonstrated in his opening-round bout against Patrick Smith, his specialty was leg locks – especially the heel hook.

But after a quick and fiery win over Smith, Shamrock was submitted with even greater speed by Gracie, who managed to use his gi sleeve to add leverage to a sort of modified bulldog choke in the opening minute of the bout. Shamrock tapped, prompting Gracie to release him, even if the referee missed it. This prompted Gracie to angrily insist that Shamrock admit to tapping out, which he did, with a somewhat surprising graciousness.

With Gordeau easily downing Rosier via strikes, the finals were set. But lest anyone get confused about the limits of impartiality, the event also saw a pause to honor the martial arts contributions of Helio Gracie, the patriarch of the Gracie family.

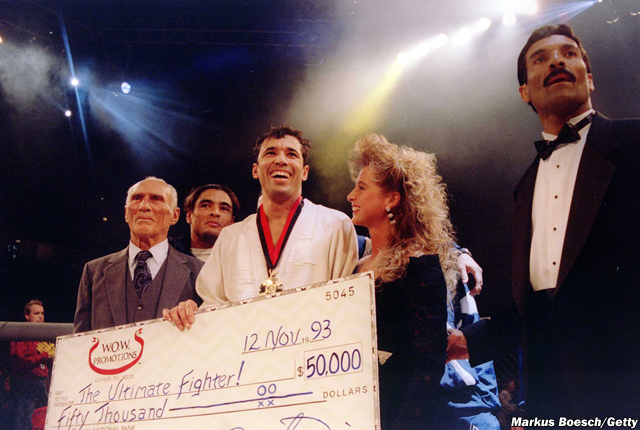

Maybe then it shouldn’t have been such a surprise to see Royce take Gordeau down, move to his back, and then finish him with a rear-naked choke in the finals. This was always the end that the event organizers envisioned, after all. And as a method of spreading the gospel of jiu-jitsu, it worked remarkably well. The tournament produced the desired visual, with the physically unimpressive Gracie jiu-jitsu fighter conquering a series of larger, more intimidating foes until he alone stood as the winner of the $50,000 grand prize.

Just as importantly, the tournament itself had gone surprisingly well. No one was seriously maimed or unreasonably injured, as it seemed early on that they very well might be. While the broadcast had its share of hiccups (and one burp), viewers were mostly too glued to the unusual action to care.

What was pitched as a bloody, barely legal curiosity suddenly started to seem like a potentially viable new entity. There might be a future in this after all. But as the crowd filtered out of the McNichols Sports Arena and the fighters headed for the hotel bar, no one could have possibly known just how much it would grow and change in the next quarter-century. Back then, who could have even guessed it would last so long?

“Today in MMA History” is an MMAjunkie series created in association with MMA History Today, the social media outlet dedicated to reliving “a daily journey through our sport’s history.”