This article is part of our #FightHoax2024 series.

Ahead of Indonesia’s 2024 general election, fact checks in Indonesia are expected to save the public from misinformation.

Media organisations and activists in Indonesia still heavily focus on social media for fact-checking activities to eradicate misinformation.

This is understandable, given social media is still the platform used the most by the public to access fact-check contents and to clarify any news they see. Not to mention that most mobile phone users (68%) in Indonesia turn to social media to access information.

Yet we seem to almost forget that our personal conversations can also contribute to the spread of false information.

A report by the Indonesian Anti-Slander Society (MAFINDO) on the spread of misinformation in Indonesia has placed WhatsApp – currently the most popular communication app in the country – as a platform for spreading misinformation.

My latest research, which I conducted with my research team from the Digital Journalism Department at the Multimedia Nusantara University (UMN) in Indonesia, shows people rarely refer to messaging apps as their main source for finding facts.

Maybe it is the time for Indonesian press and fact-check communities to intensify their fact-checking dissemination strategy by targeting instant messaging apps, like Whatsapp, Line and Telegram.

Misinformation in personal messaging apps

The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism’s Digital News Report 2021 shows that the people of Global South, including Indonesia, considers WhatsApp a medium for spreading misinformation.

This means our instant messaging activities are not really safe from hoaxes.

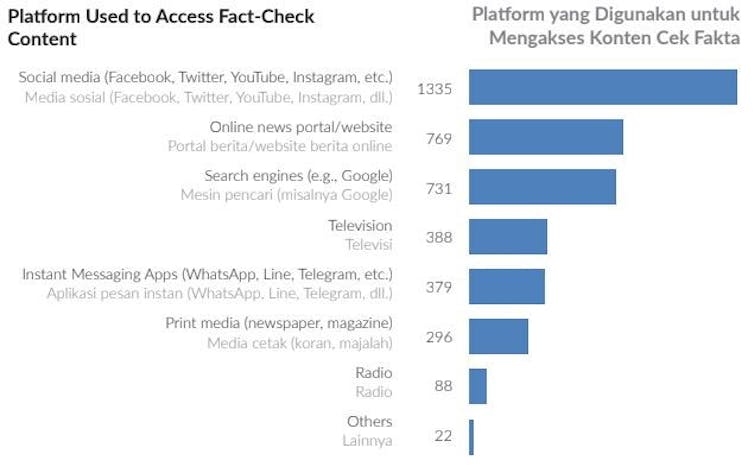

However, from total of 1,596 respondents from our research, only 379 of them use messaging apps – WhatsApp, Telegram, Line – to seek fact-check contents.

The majority of respondents (1,335) still prefer to access fact-check content via social media. Other platforms they prefer to use are news websites (769), search engines (731) and television (388).

We argue that personalised fact-checking –- through WhatsApp or other messaging apps –- is important to complement existing fact-checking strategies targeting social media.

What can fact-check communities do?

To begin with, journalists can integrate the fact-check contents they publish on social media or news websites with messaging services, especially WhatsApp.

Integration with messaging apps will increase engagement with audiences and, at the same time, expand the distribution of fact checks to combat misinformation.

Press institutions and fact-checkers can also use chat features to engage audiences. MAFINDO and Indonesia media organisation Tempo have done this. Both organisations collaborate with Whatsapp to integrate fact-checks using a chatbot technology.

The chatbots will work or respond only after receiving messages from the users. Through this feature, all users can choose to read fact-check articles or report suspicious information.

Tempo and MAFINDO’s chatbots are a good first step.

However, both are a passive technology, because they only receive fact-checking messages from readers and then respond accordingly by sending the same fact-check articles for all users. In addition, only users who have the numbers of the two chatbots can access this technology.

Based on the evidence I’ve seen , I believe we need to strengthen this approach with two strategies: push notifications and personalisation.

Push notifications use technology to automatically deliver notifications and digital content to audiences. Personalisation is an effort to map audience preferences or characteristics that can then be used as a basis to send relevant content or notifications.

Personalised push notifications

News media companies and fact-check communities could start by mapping their audience database, based on gender, occupation or location, as well as people’s reading time online.

Fact-check consumption patterns are closely related to audience characteristics. So, media companies could create databases to map different audiences’ interests in fact-checking different topics.

After mapping their audience, the press company could send notifications on fact-check content using the personalisation and push notification strategies.

It means newsrooms would send notifications via WhatsApp to the relevant audiences. “Relevant” means that the notification contains a number of fact-checking content on topics liked by that audience.

However, we should note that push notification strategy could make errors at times. For instance, media organisations could distribute content that is irrelevant to that audience’s interests, and at the wrong time. These unguided push notifications could be very annoying to some audiences.

Therefore, personalisation and push notifications need to be present simultaneously. I call it “personalisation-based push notifications”. This would ensure users only receive content relevant to their interests.

Consent and privacy protections

But before starting any audience mapping work, media organisations should first secure consent from their users by asking them to opt in or out of having their data included.

Media companies must also guarantee that any personalised fact-checking databases or notifications would protect their audience’s personal data.

To avoid privacy breaches, news organisations and fact checkers need to invest in creating subscription systems using reliable technology.

This strategy would require investments in human resources and technology. If we could successfully implement it, our digital fortress against misinformation and misinformation will be strengthened.

It would be better if users could easily interact via chat with different newsrooms to ask for fact-checks about any issues they are interested in.

With this, more Indonesians could go from potentially spreading false information to their family and friends through personal chats, to helping share more factual, better quality information ahead of future elections.

Research on the fact-checking audience in 2021 supported by the Indonesian Cyber Media Association (AMSI).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.