Australia’s electricity system is on the road to becoming 100% renewable as coal-fired power stations close and wind and solar takes their place.

But as a proportion of electricity consumed domestically, it’s on the road to more than 100% renewable. That’s because renewable power set to be produced in Australia’s north could be exported in ways such as via subsea cables.

And if we get really serious about bringing down global emissions we will be doing much, much more.

In a newly-published study carried out as part of a multi-disciplinary team under the Zero-Carbon Energy for the Asia-Pacific project we analyse the potential for Australia to produce and export not only clean energy but also green value-added commodities, eliminating emissions that would have taken place elsewhere.

We find there is substantial scope for Australia to use its solar, wind and land endowments to become a major exporter of green electricity, green hydrogen, green ammonia, and green metals.

Australia’s exports are emission-intensive

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of coal and liquefied natural gas, mostly to countries in the Asia-Pacific. Each year, the emissions from overseas use of these fuels vastly exceed the total emissions from Australia itself.

Australia is also a major producer and exporter of other commodities that go on to be used in emissions-intensive ways in destination markets - among them iron ore, bauxite and alumina.

À lire aussi : Australia is in the box seat to power the world

The figure below shows our calculations of the “consequential emissions” associated with Australia’s exports of several key commodities.

To avoid double counting, coking coal is not shown. Its emissions are instead included in the emissions tied to the overseas use of Australian iron ore.

The consequential emissions associated with the key commodity exports shown below account for about 8.6% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the Asia-Pacific and about 4% of global emissions.

While importing countries are certainly not absolved from responsibility for emissions from use of Australian exports, the calculations show just how important Australia’s upstream role is.

Australia could export zero-carbon products and energy

To get an indication of the production possibilities, we calculated the land area and energy requirements for an indicative scenario in which Australia:

exports the same quantity of energy in green electricity and hydrogen as it exports in thermal coal and liquefied natural gas.

processes currently-exported iron ore, bauxite, and alumina into green steel and green aluminium for value-added export.

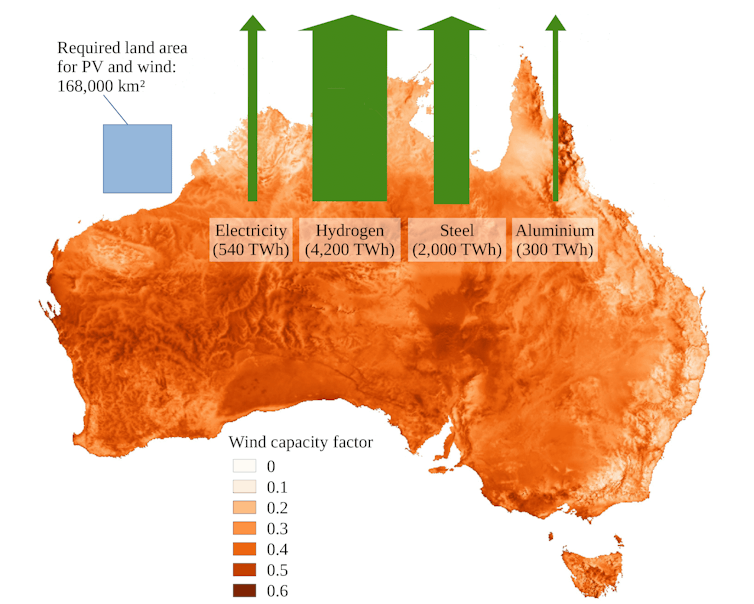

Using 2018–2019 data, we calculate that about 2% of Australia’s land mass would be needed for solar and wind farms. This is a large area, although small relative to the area currently dedicated to livestock grazing and other agricultural activities.

À lire aussi : Why Aboriginal people have little say over energy projects on their land

The energy requirement would also be large, involving about 7,000 terawatt-hours of solar and wind generation per annum – about 27 times Australia’s current electricity output and use.

Water would be needed for electrolysis to produce hydrogen. This could be largely based on desalination of seawater, an activity that would involve minimal additional energy requirements.

The best locations for mega-scale solar and wind farms for export commodities are commonly in arid or semi-arid areas outside the most productive agricultural zones, so negative implications for food supply could be avoided.

Land and electricity requirements under a zero-carbon export scenario

Key priorities include ensuring that the sustainable development opportunities for Indigenous communities from these projects are harnessed and protecting the natural environment.

Reducing the need for new coal mines and other fossil fuel projects would be a major environmental benefit.

There’s private sector interest

Australia is already a world-leader in the adoption of solar and wind power, and there is substantial private-sector interest in zero-carbon export opportunities.

Proposals for exports of solar electricity (Sun Cable), green hydrogen (including Fortescue Future Industries and the HyEnergy Project) and green ammonia (including the Asian Renewable Energy Hub, Western Green Energy Hub, and Yara Pilbara) are pointing the way.

The combined renewable electricity peak capacity for these projects alone (>100 GW) already exceeds Australia’s present electricity generating capacity by a considerable margin.

They are opportunities we should grab

Achieving the rates of investment required to realise our clean commodity export potential will require world-class policy.

In 2019 Australia released a National Hydrogen Strategy, and most states and territories have similar plans. The Technology Investment Roadmap, the Australian Renewable Energy Agency and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation are further examples of “green industrial policy” at work.

To facilitate access to premium markets, we need to ensure it is easy for new industries to prove that their production is clean. Australia is currently undertaking efforts to develop hydrogen certification.

À lire aussi : Morrison has embraced net-zero emissions – it's time to walk the talk

International regulatory collaboration is essential. Negotiations for an Australia-Singapore Green Economy Agreement are a step in the right direction.

In October 2021 Australia announced a target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Our research finds domestic emissions are only part of the story. Australia has an opportunity to contribute to global net-zero emissions via clean exports.

Paul Burke has led and worked on research projects funded by a variety of funders. None present a conflict of interest on this topic.

Emma Aisbett leads and has led research projects funded by a variety of funders. None present a conflict of interest on this topic

Ken Baldwin has led and worked on research projects funded by a variety of funders. None present a conflict of interest on this topic.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.