Environmental disaster struck the shores of Peru on Jan. 15, 2022, when Spanish energy company Repsol spilled 12,000 barrels of crude oil into the Bay of Lima after its tanker ruptured. The spill endangered 180,000 birds and destroyed the livelihoods of 5,000 families.

Although this disaster was the largest-ever oil spill in Peru, it is only the most recent of the dozens of large spills that occurred worldwide. In fact, 39 million litres of oil from offshore drilling — enough to fill 16 Olympic-sized swimming pools — pollute our seas every year.

Time and time again, offshore oil and gas activities have jeopardized coastal environments, human health and local economies. At the same time, global reliance on fossil fuels — 30 per cent of which is extracted from beneath the seabed — continues to drive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions towards the planetary tipping point.

A way out of this mess, according to new analysis conducted by conservation non-profit Oceana, is to halt the expansion of offshore oil and gas extraction, while ramping down future production. This is a critical step towards reducing global emissions.

Offshore drilling’s immense carbon footprint

Offshore oil and gas emits vast amounts of GHG, starting during the exploration and extraction below the seabed, continuing through intensive processing and refining onshore, and right up until the fuels are finally burned.

Drilling operations are dirty too. Oil extraction vents unusable and wasted gas that must be burned on the spot. This intentional flaring — burning of gas — blasts not only methane and carbon dioxide (CO2), but also toxic air pollutants into the atmosphere.

At the current rate, these lifecycle-emissions from offshore oil and gas are estimated to reach 8.4 billion tons of CO2 equivalent (CO2e, which includes CO2 and other GHG) by 2050.

Ocean solutions are climate solutions

Ocean-based climate solutions envision a healthy ocean that provides both nature- and technology-based opportunities to limit the worst impacts of climate change.

Simply by existing, the ocean acts as a buffer against the impacts of climate change. It absorbs more than two-thirds of human-produced CO2 and 90 per cent of the excess heat trapped by GHG pollution. Connecting science with concrete policy actions, however, is needed to drastically cut emissions and achieve global climate targets.

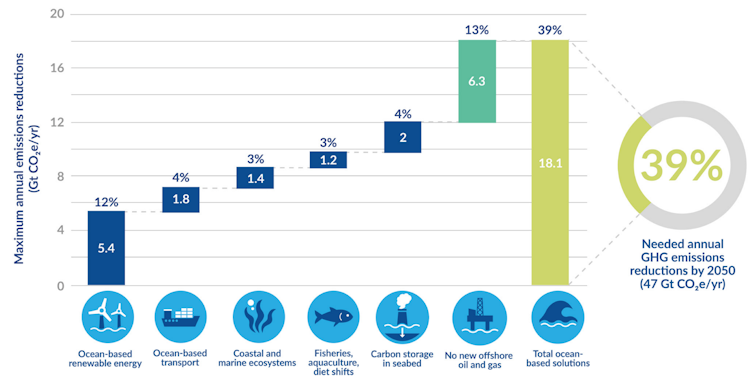

Experts previously examined the potential of five ocean-based solutions — ocean-based renewable energy, ocean-based transport, coastal and marine ecosystems, fisheries and marine aquaculture and seabed carbon storage — to mitigate global emissions.

Scaling up offshore renewable energy could significantly cut the need to burn coal for electricity. Meanwhile, co-ordinated efforts are already underway to decarbonize global shipping fleets. Seabed carbon injection remains a contested option to directly capture CO2, as concerns about its risks and scalability persist.

The nature-based solutions hold promise as well. Protecting and restoring coastal ecosystems like mangroves, seagrasses and saltmarshes will amplify their ability to drawdown and lock carbon away. Replacing emissions-intensive food options with climate-smart seafood protein ensures better climate and nutrition outcomes.

Ocean-based solutions can cut emissions

For the first time in UN Climate Conference history, earlier this month, leaders at COP27 in Egypt were mandated to prioritize national ocean climate actions under the Paris Agreement.

But after a week of negotiations, COP27 ended with a whimper as delegates failed to agree to a phase down of fossil fuels. In fact, fossil fuel industry delegates in Egypt outnumbered those from the ten countries most affected by climate change. Without collective opposition, fossil fuel interests will continue to deliberately thwart policy plans to reduce emissions.

The Oceana study put a number on GHG emissions that could be averted if countries cancelled their inactive offshore drilling leases and prevented tapping into any new fields. Instead of continuing investments in dirty and dangerous offshore oil and gas, their funds should support renewable energy development to meet our future energy demands.

The International Energy Agency modelled future oil and gas production under exactly those conditions. The net-zero emissions by 2050 scenario predicts that ambitious investments in renewable energy will go hand-in-hand with the gradually declining offshore fossil fuel production. By 2050, the annual emissions averted — 6.3 billion tons of CO2e — would be equivalent to taking 1.4 billion cars off the road.

Combined with the other ocean climate solutions, stopping new offshore drilling would close nearly 40 per cent of the emissions gap needed to meet the Paris Agreement.

But without immediate policy interventions, more untouched oil and gas reserves from the sea will be extracted, burned and generate planet-warming CO2.

When ocean conservation meets climate priorities

So is it actually feasible to halt expansion of all new offshore drilling?

Currently, only 10 countries dominate 65 per cent of the offshore oil and gas market. By 2025, around 355 new offshore oil and gas projects across 48 countries are slated to start operating. At COP27, some coastal African nations expressed intentions to tap into fossil fuels to improve energy access.

But locking in more offshore drilling leases will not ensure energy security or necessarily lower fuel prices. Oil companies continue to rake in record profits. New drilling will, however, trap coastal communities in an unsustainable industry that threatens to pollute waters, harm their health and heat our planet.

Several countries are already taking the lead in plugging this pipeline for good. Since 2017, countries like Costa Rica, Belize, Denmark, Ireland and New Zealand have stopped granting licenses for offshore oil and gas exploration.

Others pledged to ban extraction altogether, while the European Union, India and multiple island nations called for a phase down of all fossil fuel production in this year’s UN climate agreement. A new global emissions data tool released at COP27 can further help governments hold the biggest fossil fuel polluters accountable.

We are also seeing benefits of regional transitions to clean energy. In the U.S., for instance, the offshore wind industry could support 80,000 new jobs by 2030. And new markets in the Global South, like Vietnam and India, are also shifting away from offshore oil and gas.

The outcomes of COP27 fell short of the ambition needed to limit emissions on track with our climate goals. More than ever, we need our nations’ leaders to prioritize the well-being of their citizens over the wallets of the fossil fuel industry. A future with less offshore drilling is the only future compatible with clean energy access, a healthy ocean and liveable climate for all.

Daniel Skerritt is an affiliated researcher with the Fisheries Economics Research Unit at the University of British Columbia and also works for Oceana’s Transparent Oceans Initiative. The study that forms the basis of this article was fully funded by Oceana and Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Claire Huang is affiliated with Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment. She also works for Oceana. The study that forms the basis of this article was fully funded by Oceana and Bloomberg Philanthropies.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.