P Thomas is a tree lover and hobby arborist. So much so, that he likes to introduce himself as ‘Trees Thomas’, and within a few minutes of speaking to him, it is easy to see why.

The 68-year-old former BSNL Sub-Divisional Engineer is a mine of information when it comes to horticulture, specially the rare and indigenous trees of Tamil Nadu. He also runs a charitable trust called Trees Research Educational Environmental Services in Tiruchi.

Thomas was in the news recently for growing the ‘senthooram’ (lipstick tree, Bixa orellana) sourced from Chattisgargh in his arboretum (a botanical garden dedicated to trees) for two years in Anbu Nagar, Tiruchi, before it was transplanted to a site at Kallukuzhi.

“Trees are very clever, they will find their way no matter where you plant them,” says Thomas, who cultivates over 400 rare and indigenous species of trees on a 5,000 square feet plot near his home. The land, belonging to a neighbour, is linked to a special water connection from Thomas’s residence across the road.

Everyday, Thomas and his wife (and gardening assistant) Lourdes Mary spend hours on their passion project, tending to the trees growing in planters made out of plastic bubble water containers. “We can enter the garden only for three months in the year; once the mosquitoes and monsoons take over, we stay out,” says Thomas.

Thomas had an abiding interest in gardening, even when he was working in the Chennai Circle office of BSNL. “After settling down in Tiruchi 12 years ago, I started volunteering for groups that were developing herbal gardens in the city. But I realised that trees were not getting the attention that herbal and terrace gardens were. So I shifted my focus,” he says.

The strong Aadi wind is making its presence felt in the arboretum on a recent weekday, threatening to blow the tops off trees, but the swish and sweep of leaves provides a soothing sonic backdrop to this green patch as Thomas shares his story.

Hunt for trees

Starting off in 2013 with a hunt for the 27 ‘nakshatra’ trees considered to be auspicious and celestially linked to a person’s star sign in Hinduism, Thomas hit a speed bump almost immediately. “A plant supplier said that buying a set of 27 star tree saplings would cost ₹30,000. I decided to find them myself, and then gift them to temples. I give away saplings of nakshatra trees to at least 20 temples in a year,” he says.

As an extension of this, he started looking for the 108 ‘paadam’ trees (each of the four related to the star trees), but was able to find only 50 of them. “I was astounded to see that so many trees had been wiped out in my own lifetime. They are either extinct, or have become too widely distributed to be identified,” says Thomas.

While looking for these missing trees, he found that at least 4700 trees were native to Tamil Nadu at one time. “Referring to old books, I was able to find only around 1300 species still growing in the state. The rest, over 3000 trees, have gone missing. So I thought I would do my bit to revive at least some of them.,” says Thomas.

Branching out

Since that search seemed to be getting tangled, Thomas has begun to look for ‘Sthala Vriksham’, trees that are indigenous to historical Hindu shrines. “These trees once used to be venerated as gods before the advent of idol worship. They are different from sacred groves,” says Thomas.

“Though I am a Catholic, I have been distributing tree saplings to Hindu temples, because I feel the authorities will be best placed to take care of these indigenous species. I have also researched on the scriptures in Hinduism while studying the trees, and am quite open to sharing my knowledge with others. The trees are my priority,” he says.

He adds that at least 90 ‘sthala vrikshams’ can no longer be found in Tamil Nadu, due to which temples simply adopt any tree that is easily available.

Rare gems

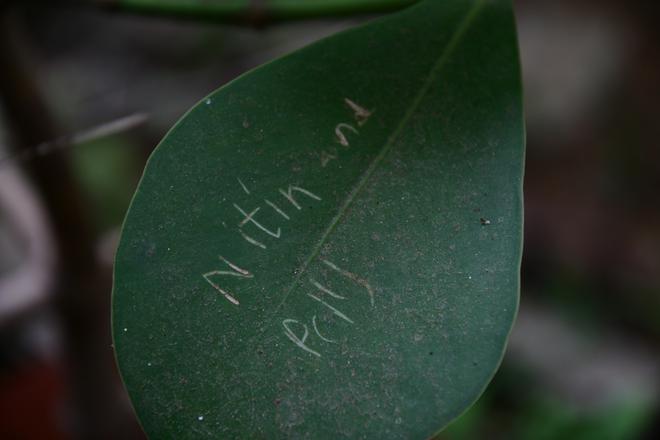

The arboretum functions as a practical study centre for students of botany, and may also be among the few repositories of rare trees that are privately maintained in the State. Among the many samples here, Thomas and Lourdes Mary point out some of their favourites. There’s the autograph tree, ( Clusia rosea), so called because the leaves can be written upon. “Our grandsons have etched out their names on this leaf, it’ll be there until it is shed,” Lourdes Mary laughs.

The ‘yaanai kundumani’ ( Adenanthera pavonina) growing here has a historic significance too; the red seeds of this perennial and non-climbing species of leguminous tree were once used as a unit of weight by goldsmiths and jewellers because they all weighed the same (0.05 grams).

We are introduced to the seven-leaf kadamba maram ( Anthocephalus cadamba), the ‘sthala vriksham’ of the Madurai Meenakshi Temple. “It is very hard to grow because the seeds are very minute and saplings are delicate,” says Thomas.

And then there is ‘iluppai’ ( Madhuca longifolia), whose thick seed oil once used to light up temple towers before electricity came into use. “Besides the concentrated seed oil, its flower can be used as a substitute for cane sugar. Traditional snacks used to be fried in illupai oil and the temple cars in those days were made out of illuppai wood. Many shrines used to cultivate groves of these trees mainly to extract the seed oil for lighting the complex. But this has died down after electricity entered the picture,” says Thomas.

Looking out for the next generation of tree lovers to share his research with, Thomas has used the lockdown months to publish Tamil books on the subject. “The trees in my garden are not revenue-earning; perhaps this is why interest in my work is limited to just botanists. I have been spending my pension on collecting seeds and saplings and it would be good if more people step up to help us save our rare trees,” he says.