“What’s this? This car? This stupid car?” John Belushi’s Joliet Jake demands, early in “The Blues Brothers,” having just been picked up from prison in a beat-up old cop car by his brother Elwood. “Where’s the Cadillac? The Caddy. Where’s the Caddy? The Bluesmobile.”

“I traded it,” Elwood says tersely.

“You traded the Bluesmobile for this?” Jake says, aghast.

“No, for a microphone,” says Elwood.

“A microphone?” Jake replies, incredulous. Then he pauses, thinking. “OK,” he concludes. “I can see that.”

Of course he can. Microphones are important. And cool. And Chicago. The nation’s preeminent microphone company, Shure, has been based here for 99 years. Under the radar, since microphones are the unsung heroes of the electronic age. Even though every phone call you make, every note of every song you hear, every desperate demand put to Alexa, is conveyed through a microphone. They matter.

Thus it made me wince to see another important, cool and very Chicago icon, urban historian Shermann Dilla Thomas, do his TikTok videos holding this tiny little microphone between his thumb and forefinger, like a man about to pop a peanut into his mouth. Sometimes it was just the wire from earbuds. Thomas is 6-foot-5. The microphone looked dinky.

I said nothing. For months. Shutting up is an art form that requires practice. People don’t take criticism well, no matter how nicely couched. I’ll read a colleague’s story and think, The lede is in the sixth graf. But say nothing. There’s no point. The story’s printed. They wouldn’t fix it; they’d just hate me.

But Thomas’ work is ongoing. And he obviously cares about what he does. So how could I sit here, silently judging him, with the solution at hand? I had to make an effort. First I reached out to the Shure folks and acquainted them with the situation. They nodded happily. Then I messaged Dilla. “I hope I’m not being presumptuous,” I began. “But lately, watching your videos, I had an odd thought, ‘He needs a better microphone....’”

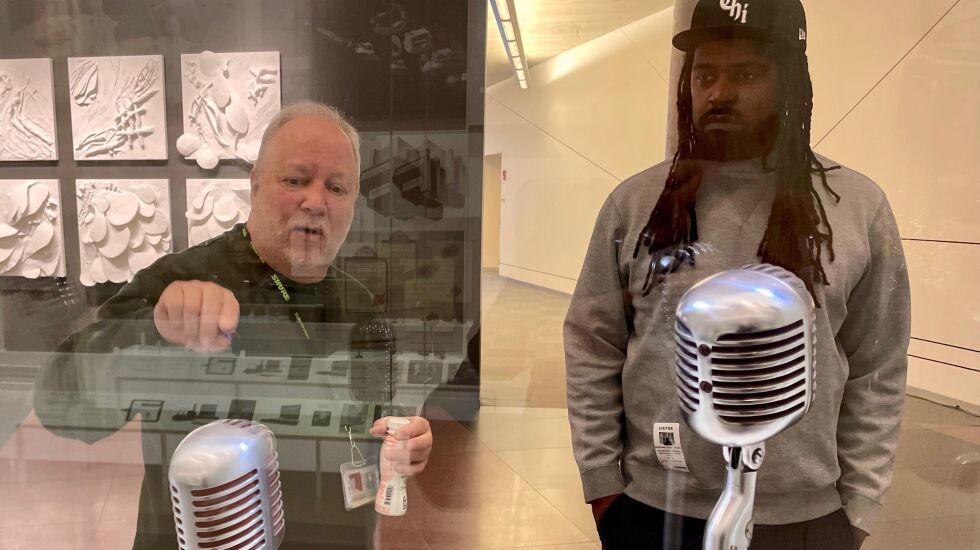

We met Tuesday at Shure’s Helmut Jahn-designed headquarters in Niles, and were greeted by Michael Pettersen, who has worked at the company since 1976. His business card reads, “Director of Corporate History” and “Sage.”

First, we toured the company’s small museum. An Emmy. A Grammy. The first wireless microphone. A headset worn by Michael Jackson. “Michael Jackson’s DNA is on that,” said Pettersen. I did not reply, “Ewww, gross.” Shutting up is an art form ...

I’ve taken the tour before, and I still learned new stuff. World War II supercharged Shure’s business. In January 1942 it had about 100 employees. A year later it had a thousand, building microphones and headsets for Navy ships and bomber pilots.

We toured their quality assurance department, saw every kind of testing — chambers that freeze microphones, bake them, spray them with artificial perspiration. Devices that twist headsets, that push buttons thousands of times. You’ve heard of a mic drop — here they drop mics.

Part of me worried that we’d get this detailed dog-and-pony show and then be ushered into the parking lot, where we’d stand, empty-handed, looking at each other. I tend not to trust people, and in the preceding days, I had so wanted to say, “You’re going to give him a mic, right?”

But just as shutting up requires practice, so does trust, and a company that has a memorial garden with plaques of departed employees is not going to drop the ball.

We ended the tour in a room with a table that looked like Christmas without the tree. Boxes of microphones, cables, earbuds.

“That’s crazy,” said Thomas, listening to himself. “It sounds like a radio station. This is going to make the rest of my videos sound terrible. I didn’t know what I was doing before this.”

Neither did I. Microphones, as I said, are underappreciated, and I never considered that the Shure microphones would also sound far better. I just wanted something that would look impressive. The model 55 — issued in 1939, barely changed since — was the one microphone left untouched. I picked it up, held it in my hand, admiring its heft. Then sighed and gave it to Dilla. “You’ll want this one too,” I said.

A snowstorm had started while we were there. My work done, I headed out into it.