I don’t like to dwell on the past,” Tina Turner said, whenever she was asked to retell the story of her loveless childhood and the long, abusive marriage she fled in 1976. She’d prefer we remember her as a “rock goddess”, the first Black artist to appear on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine in 1967, and the first woman over 40 to top the Billboard charts in 1984. “But I get cards, letters… People said I gave them hope. I have to pass that on.”

If the singer, who died on Wednesday aged 83, feared being remembered as a victim, then those fears were unfounded. Because it’s her mighty roar of survival and triumph that fans will continue to celebrate. Each night in London, audiences rise to their feet as they watch her story retold in Tina: The Musical. A theatrical event that the star initially resisted but eventually blessed, rocking up to rehearsals, aged 79, to show actors half a century younger how to perfect her super-strutter dance moves. Turner had sweat so hard that the wardrobe department fetched her a fresh blouse.

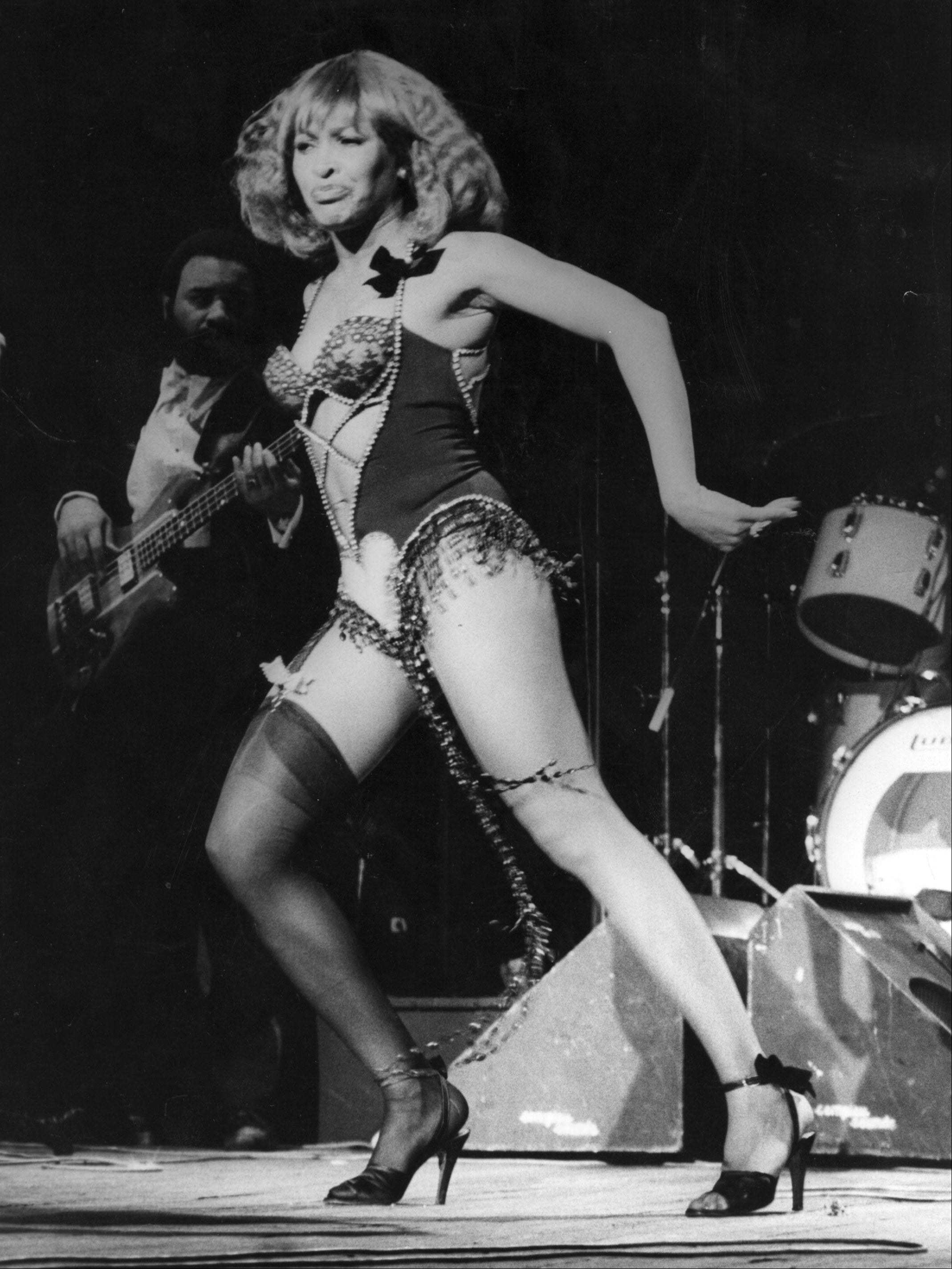

I visited the theatre a few weeks before the curtain first rose and ran my hands down the long rack of costumes that marked Turner’s transition from the raggedy Baptist choir singer, through R&B revue act, to leather-mini-skirted rock goddess. “When I look back, I can see the story of my life through the clothes I wore,” she told NBC in 2020. “The opportunity to sing with Ike [Turner] in the early days was like something out of a fairytale for a teenager whose dream was to perform onstage. I felt so elegant in my gown, like a princess. But that gown was a prison, just like my marriage. I wanted to move, so my skirts got shorter and less constricting because freedom was important to me, onstage and in life.”

Backstage in 2018, my eyes settled on the coat-hangers from which they were hanging. Ike Turner used coat-hangers to beat his wife (along with shoe stretchers and other dressing room paraphernalia) because he didn’t want to damage his delicate, guitarist’s fingers on her face, ribs, arms or the extraordinary legs she’d later insure for $3.2m (£2.6m). Before Turner left those London rehearsals, she gave a parting note to those she was entrusting with her life story: “Don’t make it Disney.” There was nothing Disney about it.

Tina Turner was born Anna Mae Bullock in 1939. She grew up in the rural town of Nutbush, Tennessee (the “City Limits” she added to the lyrics of the song she wrote about it was a joke). Fifty miles northeast of Memphis, the town was founded by European settlers who brought enslaved African Americans to work the cotton plantations. Turner’s father was a plantation overseer for the white Poindexter family, on whose television little Anna Mae would watch the white, female singers of the 1940s and feel herself too tall and dark-skinned for a career on the stage. She was a tomboy. A basketballer and an adventurer. “I was the child who always had scraped knees and tousled hair because I climbed trees and rolled in the grass,” she said.

In her 1986 autobiography, I, Tina, Turner wrote that neither of her parents had loved her. Her mother had been trapped into marriage by pregnancy and eventually fled home when the youngest of her three daughters was aged just 11. She spent the next five years under the thumb of her strict grandmother. When her grandmother died, she was shunted back into her mother’s care in St Louis where she’d go to hear Ike Turner's groundbreaking band.

Although an appalling human, Ike had arguably invented rock’n’roll with the 1951 single “Rocket 88”. Each night he would pass around a mic to women in the crowd. Although Ike liked to pretend he’d discovered and invented his wife, it was Anna Mae who seized the microphone after he’d repeatedly passed her over in favour of girls he found more attractive. Later, it was a record producer with great ears who advised Ike to make “that girl” the star of his act.

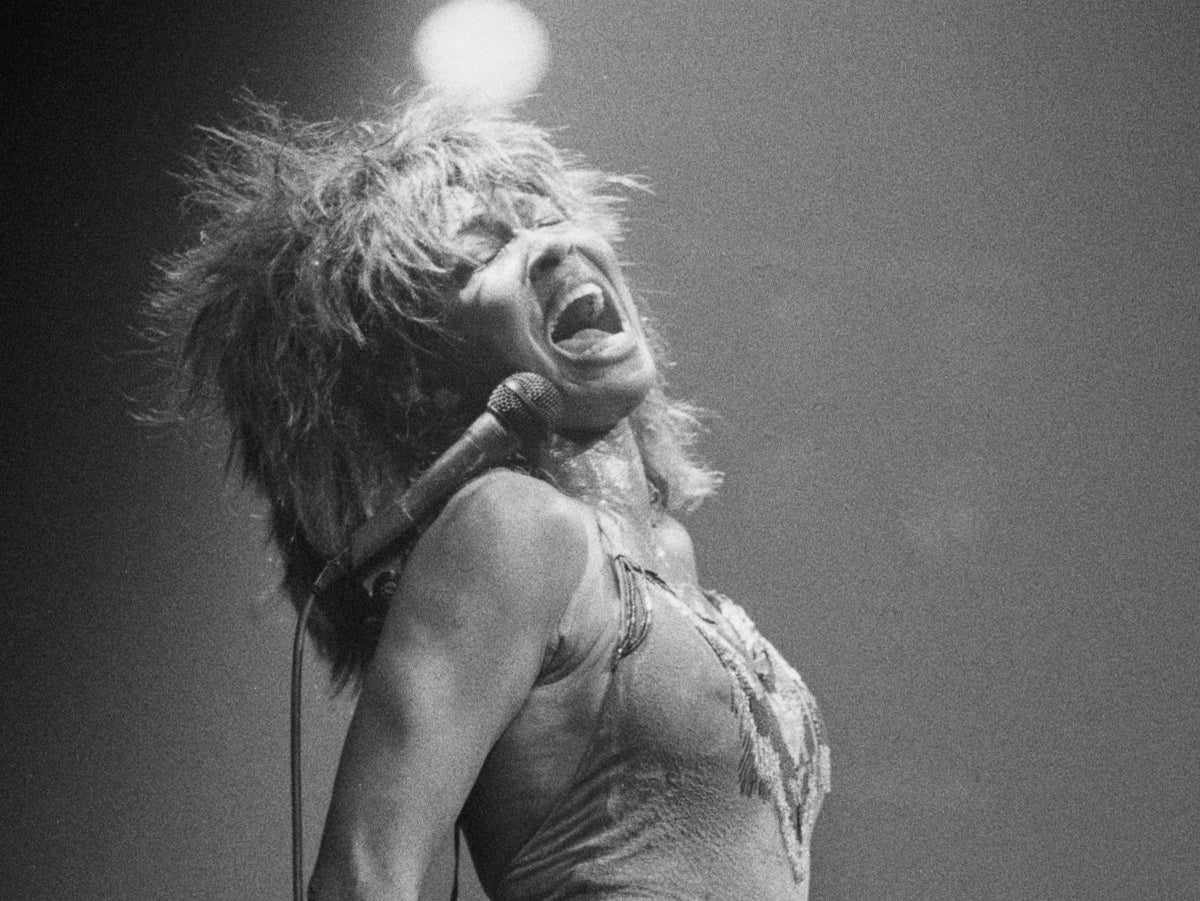

Her raw, sucker-punch vocals were a perfect match for the speedy funk-rock of his band. You can still hear it on their Grammy-winning 1971 cover of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Proud Mary”, which starts at a lollop and (rather like Tina’s career) storms into rollicking second act because, as she says, “we never do nothing nice and easy”.

That was as true of their life offstage. Over the 16 years of their marriage, Turner battered his wife. By the mid-Seventies, he was heavily addicted to cocaine. He’d turned their LA home in which they were raising their sons into a pimp’s paradise, with a mirrored ceiling on the bedroom ceiling for Ike to admire his many mistresses from all angles. His assaults on Turner led to her contracting bronchitis, which became pneumonia, tuberculosis, and a collapsed right lung.

He beat her for the last time on 3 July 1976 when on tour in Dallas. She fled from him down back alleys and across an interstate access road; her face was bruised and bloodied. She had 36 cents in her purse. She woke up, sore and determined, on Independence Day and she remade herself. That part of her story tends to get skimmed over. Because the rebuilding of Tina Turner took eight long, gruelling years, during which she took cleaning jobs to keep herself afloat while fighting for the right to her name and earnings.

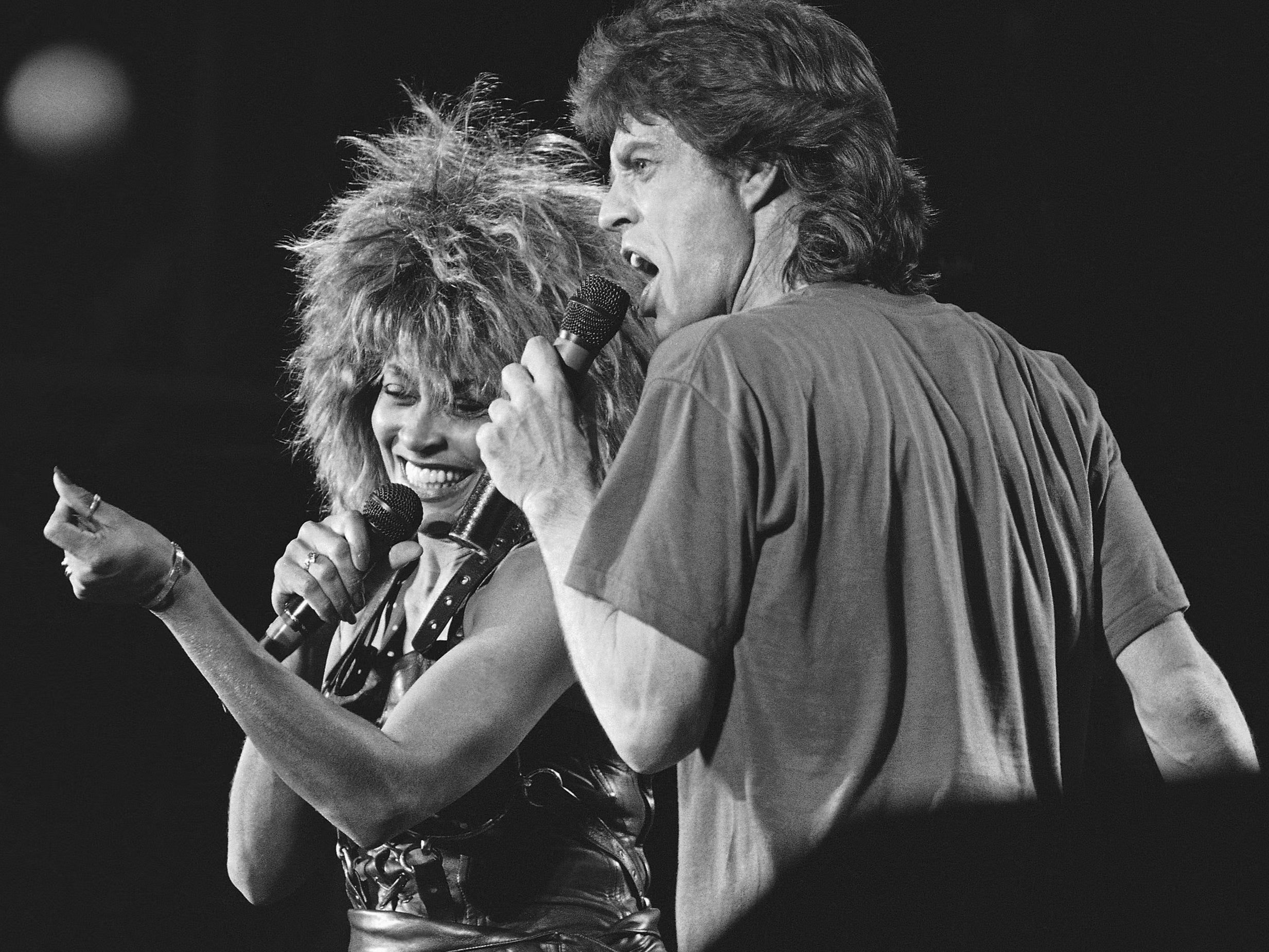

But her reinvention – in England – in the 1980s was a heart-bursting triumph. She’d always sounded unstoppable, and now she truly was. The hits and acclaim, which Ike had craved for himself, became hers. In the process, she broke down barriers for those who would follow her. She proved that Black singers could sing rock.

She proved older women could scale the charts. I saw Turner on her final tour in 2007. “What’s Love Got to Do with It?”, “The Best”, “Private Dancer”, “We Don’t Need Another Hero”, “Typical Male”, and Bond theme “Goldeneye” – she belted out them all. At 69, Turner brought a blazing soul fire to the chilly, corporate atmosphere of the O2 Arena. High-kicking and elbow-flipping in golden sequins, she outshone the fireworks that crackled from either side of the stage. She shook her hair like a lion’s mane as she performed 1984’s “Better Be Good To Me” – a song that hammers out precisely and uncompromisingly what a woman should expect from a relationship.

This was the love she eventually received from her second husband, Erwin Bach, who gave her one of his kidneys in her final decade. Turner ended her final tour by bowing so low that her nails scraped the stage, humbled by a roar of applause that matched her own. She liked to joke that her superpower was dancing in six-inch heels. But – speaking on behalf of the 1.7 million women who experience domestic violence in England and Wales each year – the Chief Executive of Women’s Aid told attendees of the fifth-anniversary performance of Tina: The Musical that her true superpower was being “a beacon of inspiration”. Long may her music light the fires of hope.