A new star is born. The British firmament of modern political and military history is already a glittering one, but established names must now make way for a new companion, Timothy Pleydell-Bouverie. His first book, Appeasing Hitler: Chamberlain, Churchill and the Road to War, was a deserved success. His second, Allies at War: The Politics of Defeating Hitler, proves that his debut was no flash in the pan.

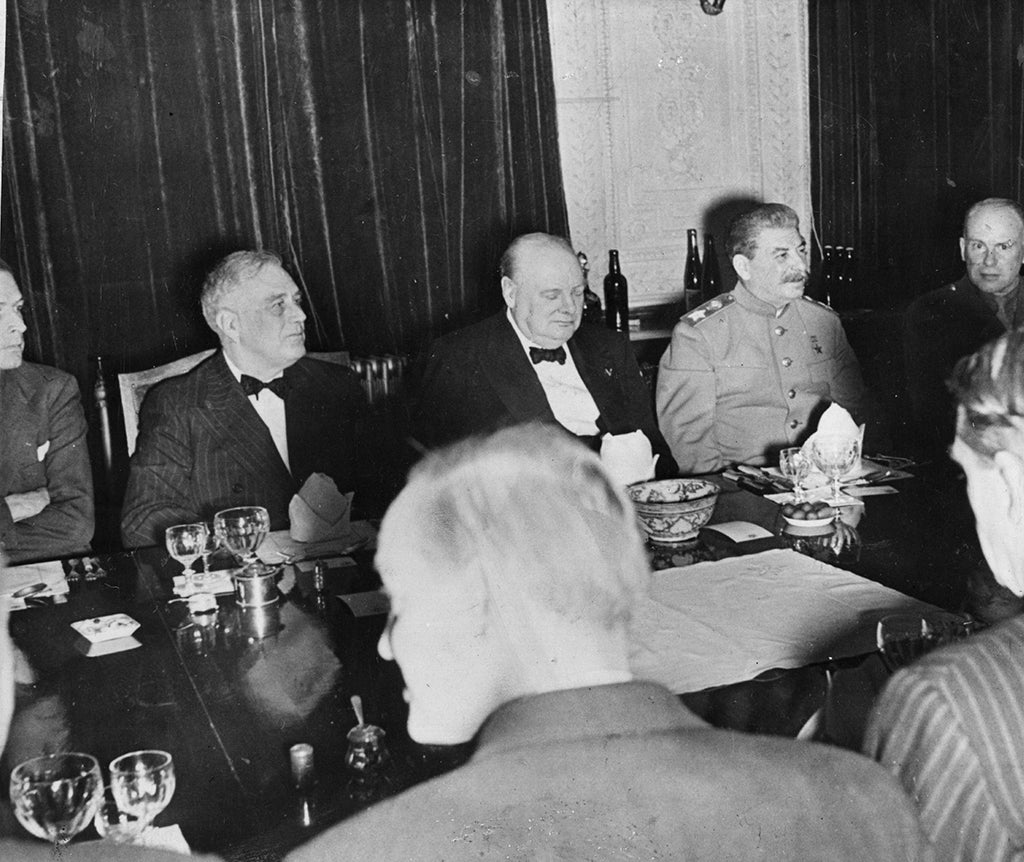

Bouverie’s scope is wide, taking in the history of those relationships, which lay behind the creation and maintenance (just) of the greatest military alliance the world has ever seen: the British Empire, the United States, and the Soviet Union. We start with British policy based on the presumed rock of the French army; with Stalin supporting the German economy and war machine after the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact; and with western outrage at Russia’s invasion of Finland in 1939. In London sits the unpleasant figure of Joseph Kennedy Sr, the US ambassador, delighting in what he foresaw as the inevitable defeat of Britain. We end with the total victory of the Big Three: Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin, the last now our beloved Uncle Joe. And Poland, for whom we first went to war, betrayed.

Churchill understood that winning would be, for the democracies, a matter of maintaining public support. He often drove the chiefs of staff mad with schemes that made no sense at all in military terms, but were designed to build pride in the honour of the cause for which free people were fighting. Churchill’s ludicrous plot for a second British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to return to France after Dunkirk; his insistence on the doomed defence of Greece and his unswerving defence of France (in spite of all Charles de Gaulle’s insults) – all these derived partly from his sense of chivalry but also partly from his understanding that people had to believe in what they were fighting for: survival, yes, but honour, too.

In the period when the British Empire was fighting alone, it was vital to show the likes of doubting US ambassador Kennedy that we would fight, and would not be defeated. We were not the lost cause that the isolationists claimed. A good many desperate enterprises were undertaken to demonstrate that we were serious, including the partial destruction of the French Fleet at Mers-el-Kebir – allies who were friends only weeks before. In what is news to this reviewer at least, Bouverie shows that Churchill had cleared this with Roosevelt in advance.

After Hitler’s invasion of Russia, and then following Pearl Harbour, the great alliance – which in the end would defeat the Axis forces, was formed. In his book, Bouverie lays clear both its strengths and its weaknesses. Its strength was their common enemy; its weakness was their irreconcilable post-war aims.

Roosevelt passionately believed in the construction of a new world order, safe for the world and also for the almighty dollar. He was wholly unsentimental about his British ally’s future. Very hard bargains were driven in return for the supply of armaments – including forced sales to US interests of British overseas assets. Britain had rebuilt her net overseas assets after the First World War; all those and more were effectively sold cheap for dollars in the Second.

Unlike the Soviet Union, who likewise received massive US (and very considerable British) aid, we went on paying for all this to the US until the first decade of the 21st century. All our military secrets, Bouverie shows, were given to America, up to and including the atom bomb research. Bouverie could have mentioned penicillin, too. Nothing came the other way. But it was necessary: we had nothing else to trade. The Red Army drove west in Michigan-made Chevrolet trucks, but Stalin obliterated any memory of the Western help without which Russian heroism might well not have been enough.

The unity of the Big Three was often fractious and worse: Roosevelt could humiliate Churchill in front of Stalin every bit as much as Trump humiliated Zelensky in the White House. Bouverie charts the personal fallings-out and the reconciliations with great sensitivity and sometimes humour. Dreadful and dangerous beliefs in personal relationships often had terrible consequences. Poland was ultimately sacrificed at least partly because Roosevelt, and for a time Churchill too, genuinely trusted Stalin. Horrible things were agreed at Yalta and before involving the repatriation of people to their deaths in the Soviet Union – Uncle Joe was, after all, such a good chap.

Reading this powerful and well-researched book left this reviewer with one very uncomfortable feeling. Read from the point of view of an isolationist, right-wing American political adviser of today, you could find precedent in what the sainted Roosevelt’s did to the British for just about everything President Trump’s administration is currently doing to Ukraine. “Take their assets to pay for any help we give! Settle the boundaries of Europe in a way that satisfies Uncle Joe/my friend Putin! Russia’s interests do not really diverge from America’s! Good old Vlad just wants safe borders. Britain/Ukraine/Europe is on the way out anyway. And I have looked into Uncle Joe’s/my friend Putin’s eyes and I know I can trust him!”

But Roosevelt had another, very different side to him that ensured his legacy. He was determined “not to do a Woodrow Wilson” by letting the US scuttle home after the war to leave the world brewing up its next one. He believed profoundly in the values of liberal democracy and wanted his legacy to be a framework for peace, which would have the power and the prestige to prevent war. He left the embryonic UN and the Bretton Woods structures to try to ensure it. Roosevelt understood that the interests of the US and the almighty dollar depended on worldwide order. His safe place in history derives not least from his recognition that American power was the power of a law-based nation, and that spreading a law-based order was not only in the interest of his own people, but of the world as a whole. President Trump is said to admire FDR: he gets the ruthlessness, but does not seem to understand the greatness.