Peace talks aiming to end the nearly two-year-old war in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia have started in South Africa, although the chances of bringing the conflict to an immediate stop are believed to be low.

Representatives of the Ethiopian government and a team sent by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a political organisation that has ruled the northern region for decades, are to spend five days together in the most serious effort yet to find a negotiated solution to the conflict.

International calls for a halt to the war have been mounting in recent weeks. Violence has intensified as both sides seek success on the battlefield to strengthen their negotiating position.

The talks have been organised by the African Union (AU), which represents more than 50 countries on the continent.

Moussa Faki Mahamat, the chair of the AU Commission, said he had been encouraged “by the early demonstration of commitment … by the parties … to silence the guns”.

In recent days, Ethiopian federal forces have wrested control of several key towns in a late push to strengthen their position before the talks.

Kindeya Gebrehiwot, a spokesperson for the Tigray forces, said the TPLF wanted an immediate cessation of hostilities, unrestricted humanitarian access and the withdrawal of forces from neighbouring Eritrea, which have fought alongside Ethiopian federal troops throughout the conflict.

“There can’t be a military solution,” Gebrehiwot said on Twitter on Monday.

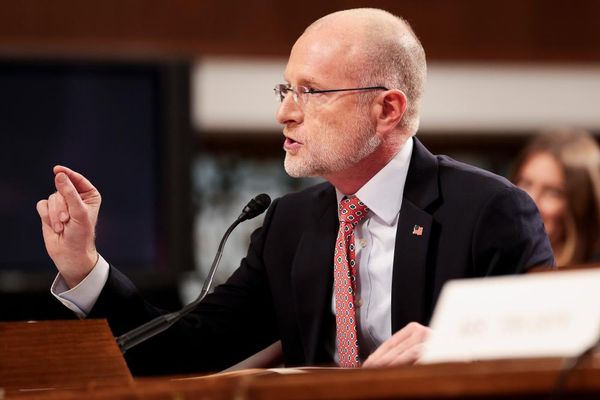

The Tigray delegation flew to South Africa on a US military aircraft accompanied by Mike Hammer, the US special envoy to the Horn of Africa. The delegation is led by a senior general, Tsadkan Gebretensae, an official familiar with the talks said.

The conflict between the TPLF and Ethiopian central government forces began in November 2020 when Ethiopia’s prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, sent troops into Tigray after accusing local forces of an attack on government military bases.

A ceasefire agreed earlier this year collapsed in August, leading to bloody battles in which thousands have died and many more have been displaced.

The UN said this month that the situation was spiralling out of control and inflicting an “utterly staggering” toll on civilians.

António Guterres, the UN secretary general, has described the conflict’s “devastating impact on civilians in what is already a dire humanitarian situation” and called for an end to hostilities.

Tigray’s 6 million inhabitants have suffered under a blockade since the beginning of the war, with limited humanitarian aid.

Almost all communications have been cut off, and banking and other commercial services have ceased. Healthcare has been reduced to minimal levels as facilities shut and medication runs short. Food, fuel and electricity is now scarce.

Human rights campaigners have warned of potential abuses. A series of airstrikes have hit what appear to be civilian targets, though Ethiopian officials deny this, and witnesses reported heavy shelling of civilian centres such as Shire, a town where an International Rescue Committee aid worker was among three people killed last week.

“Atrocities by Ethiopian and Eritrean forces after the previous capture of towns in Tigray heighten concerns for the civilians remaining in Shire and elsewhere of more killings and other abuses, and mistreatment in displacement camps,” said Human Rights Watch, the US-based organisation.

Tigrayan rebel forces are also alleged to have committed abuses, with reports of a massacre of dozens of civilians during an occupation of a town in the Amhara region after fighting resumed last month.

The alleged killings are said to have taken in the town of Kobo, located along the highway to the capital, Addis Ababa.

Between 13 and 15 September, TPLF fighters shot dead unarmed civilians they suspected of supporting federal forces and local militias, survivors have told the Guardian. In one district of Kobo alone, witnesses counted 17 bodies of people killed over two days.

South Africa “hopes the talks will proceed constructively and result in a successful outcome that leads to lasting peace for all the people of our dear sister country Ethiopia”, said Vincent Magwenya, a spokesperson for the president, Cyril Ramaphosa.

The aim of this first round of talks is “deliberately modest”, a second South African official said, with the main objective restricted to “setting the parameters for further discussions”.

A statement from Addis Ababa said the government of Ethiopia “views the talks as an opportunity to peacefully resolve the conflict and consolidate the improvement of the situation on the ground”.

Fighting appeared to be continuing even as delegations travelled to the talks. Aid workers contacted by the Guardian on Sunday said they were receiving reports of skirmishes in the north and southeast of Tigray.

Analysts say the minimum necessary for a durable peace agreement would be a temporary ceasefire and an end to the blockade – concessions that neither side appears ready to make. The presence of Eritrean troops and the role of local paramilitaries in the war will also complicate any peace negotiations.

The true death toll is unknown but could be approaching levels that make the conflict one of the most lethal anywhere in the world. With no access for independent journalists and a limited presence of international humanitarians, reliable data is scarce.

Researchers at Ghent University have calculated that several hundred thousand people in Tigray may have lost their lives since the outbreak of the conflict, including those who have died from a lack of healthcare and after being weakened by widespread malnutrition.

More have died in neighbouring regions, and the total would put the war in northern Ethiopia among the most deadly in recent decades.

The Ethiopian government accuses the TPLF, which played a leading role in the country’s ruling coalition until Abiy came to power in 2018, of trying to reassert Tigrayan dominance over the entire country. Tigrayan leaders accuse Abiy of repressive government and discrimination. Both deny each other’s accusations.

The war has further destabilised the volatile Horn of Africa region and complicated Ethiopia’s diplomatic relations with western allies, who have been calling for a ceasefire.