This is the third post in series on the Tibetan Uprising. This one is about 1956-57, when Tibetans liberated almost all of Eastern Tibet, and preparations for a unified national resistance began. Impressed by the Tibetans' success, the U.S. C.I.A. began to provide arms and training.

Post 1 covered Tibet before the 1949 Chinese invasion, including the Tibetan government's refusal to heed the 1932 warning of the Dalai Lama to strengthen national defense against the "'Red' ideology". Post 2 was the Chinese conquest, followed by armed uprising of the people, precipitated by gun registration.

These posts are excerpted from my coauthored law school textbook and treatise Firearms Law and the Second Amendment: Regulation, Rights, and Policy (3d ed. 2021, Aspen Publishers). Eight of the book's 23 chapters are available for free on the worldwide web, including Chapter 19, Comparative Law, where Tibet is pages 1885-1916. In this post, I provide citations for direct quotes. Other citations are available in the online book chapter.

1956—Kham Explodes

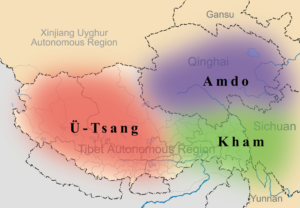

In the early 1950s, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) annexed Tibet's two eastern provinces--Amdo and Kham--into adjacent Chinese province. Pursuant to the Seventeen Point Agreement, which Tibet was forced to sign in 1951, U-Tsang province (Central Tibet, including Lhasa, the national capital) was supposed to retain internal autonomy.

But in 1956, the Chinese transferred almost all political power Central Tibet to a new entity they controlled, the Preparatory Committee for the Autonomous Region of Tibet. The Central Tibetan national assembly and cabinet (Kashag) became nearly powerless. Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang, Four Rivers Six Ranges: Reminisces of the Resistance Movement in Tibet 39 (1973). In Eastern Tibet--Amdo and Kham provinces--the pace for imposing communism was accelerated.

The Golok tribe, in southeast Amdo province, had been fighting the Chinese army since 1954. The Chinese brought in reinforcements to their so-called "People's Liberation Army" (PLA) in 1956. An 800-man PLA garrison was wiped out by Goloks and allied Tibetan Muslims on horseback, armed with muzzleloaders (16th-17th century firearms) and swords.

Even more PLA came, and they burned more monasteries, stole the livestock, and slaughtered the women and children. The surviving men had lost everything, and they took to the hills vowing to fight the Chinese for the rest of their lives. The outside world knew nothing of the Golok and Muslim revolt at the time.

At the large Lithang monastery in Kham, the communists had attempted to confiscate the monastary's arsenal in 1955, but backed off when the the lamas refused. (Post 2.) The communists came back in 1956 and arrested the lamas at the spring religious festival. Then, thousands of armed people assembled to protect the lamas and the monastery complex. The PLA shelled the monastery with artillery, and then sent in infantry. In fierce combat at close quarters, the PLA prevailed after the defenders ran out of ammunition. Finally, on March 29, the monastery was bombed by Ilyushin-28 jets, purchased from the Soviet Union. Then the Chathreng monastery was bombed on April 2, and the Bathang monastery on April 7.

In the Nyarong region of Kham, the communists were going village to village to confiscate arms. After confiscation, the communists would hold "struggle sessions." Struggle sessions were pervasive wherever Chinese tyrant Mao Zedong reigned. Individuals would be brought before large group meetings that all locals were required to attend. The locals would be ordered to scream at the victims and denounce them for being counterrevolutionary, and sometimes to physically assault them. The victims would be required to confess to various sins against Mao. At the end, victims might be released, imprisoned, sent to a slave labor camp, or executed.

A revolt was planned for eighteenth day of the first moon in 1956. In the Upper Nyarong region, the local chief and his elder wife had been summoned to a meeting by the Chinese, and so the younger wife, 25-year-old Dorje Yudon, had leadership responsibility for the first time in her life. (Polygamy and polyandry were long-standing customs in Tibet. Poly families often consisted of one husband and two sisters, or one wife and two brothers.)

Dorje Yudon gathered her men and weapons and dispatched missives all over eastern Tibet, urging the people to rise against the Chinese. Dressed in a man's robe and with a pistol strapped to her side, she rode before her warriors to do battle with the enemy. She ferociously attacked Chinese columns and outposts everywhere in Nyarong.

Roger E. McCarthy, Tears of the Lotus: Accounts of Tibetan Resistance to the Chinese Invasion, 1950-1962, at 107 (1997). Dorje Yudon's band of warriors numbered in the hundreds, and nearly four thousand people in the area joined the revolt, about 17 percent of the population, and including participants from the large majority of households. Eventually, the PLA wore the Dorje Yudon group down to only 200, at which point some escaped to India.

Revolts were spreading all over Kham. In Ngaba (northwest Kham), three thousand rose up in 17 townships in March, and by May their numbers had quadrupled. Sixteen thousand rebels were in 18 counties of Garze (west Kham) by the end of March 1956. "In early 1956, Chamdo, Lithang, Bathang and Kantzu were temporarily overrun and the Chinese garrisons stationed there completely wiped out." Six thousand Tibet irregulars "ranged freely from their mountain hideouts, wreaking widespread havoc and destruction." Andrugtsang at 47.

Tibetans were not the only ones revolting. Southestern Tibet extended into the multiethnic area today called China's Yunnan province. There,

The Yi in the Liangshan Mountains, who call themselves Nuosu, had managed to maintain their social, cultural, and political identity virtually intact up to the mid-1950s, when Beijing attempted to integrate them into the socialist polity and society. Initial, gradualist attempts were quite successful, but radicalization of the process after 1956 provoked massive resistance in the form of a several-year guerrilla war against the Communist mission of eliminating the "reactionary slaveholding society."

Thomas Heberer, "Nationalities Conflict and Ethnicity in the People's Republic of China, with Special Reference to the Yi in the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture," in Perspectives on the Yi of Southwest China 215 (Stevan Harrell ed. 2001).

By the fall of 1956, tens of thousands of guerillas had arisen in Eastern Tibet. Many fighters had started with no knowledge of guerilla warfare. They were ordinary people who banded together and attacked the communists who were destroying their communities. As the rebellion continued, smaller guerilla groups formed. Some of the fighters called themselves the Volunteer Army to Defend Buddhism (Tib., Tensung Dhanglang Magar).

Based in the mountains, the mounted guerilla Khampas, Amdowas, and Goloks burned Chinese outposts, destroyed Chinese garrisons, and raided western China. The PLA rushed in more soldiers, bringing the total force in Tibet to 150,000. Guerilla organization was facilitated by Tibet's six thousand monasteries, which functioned as the resistance's information network. The population helped with information, too; for example, when the PLA was nearby, village women warned the guerillas by hanging only red laundry out to dry.

"In thousands of square miles . . . no Han [China's dominant ethnic group] dared set foot without backup. Only the strongest Chinese bases were safe from attack." Mikel Dunham, Buddha's Warriors: The Story of the CIA-Backed Tibetan Freedom Fighters, the Chinese Invasion, and the Ultimate Fall of Tibet 168-69 (2004). PLA who rode more than a day from base were usually ambushed. On the road from Kham to Lhasa, PLA supply convoys had to travel in groups of 40 or 50 trucks, heavily guarded, advancing slowly for fear of ambush around every corner. For several months, nearly all of Eastern Tibet was cleared of the PLA and CCP. "By 1956, the PLA had, at best, wobbly control over the eastern province of Kham and, to a lesser extent, Amdo and Golok." Id. at 5.

Tibet had been easy to conquer but was hard to tyrannize.

Gompo Tashi Andrugstang prepares to unify the uprising

In the national capital of Lhasa, in Central Tibet, lived a wealthy businessman, Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang. He came from Lithang, Kham. The Andrugtsang family ran one of the four big international trading houses in the province. Like many wealthy Tibetans, he owned a large arsenal. As a teenager, he had served in a posse that captured mountain bandits; the experience made him very interested in firearms, hunting, and shooting. During World War II, Gompo Tashi had purchased many modern firearms via Burma, Laos, and India.

As refugees from Lithang arrived in Lhasa, they urged that more fighters be sent to Lithang. Gompo Tashi disagreed. In his view, it was time for Tibetans to unite, to create a central fighting force for the entire nation, not just for their native regions. Businessmen should liquidate their assets and turn them into weapons and ammunition. People had already lost homes, families, and monasteries. There was nothing left to lose.

In October 1956, Gompo Tashi began networking for an all-Tibet army. He soon sent emissaries to Eastern Tibet; ostensibly they were on a business trip. In fact, they were carrying his message that "the Tibetans now have no alternative but to take up arms against the Chinese." Andrugtsang at 42-43.

The outside world heard very little about the Tibetan resistance. There was no foreign press in Tibet, and only India, Nepal, and Bhutan had diplomatic representatives in Lhasa. Refugees escaping to India sometimes carried firsthand reports, which were published in the Tibetan language newspaper Tibet Mirror in Kalimpong, India, run by a Christian missionary. But Indian Prime Minister Nehru banned further dissemination of Tibet revolt news, calling it "anti-Chinese propaganda." Jianglin Li, Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959 at 28, 42 (2016); Dunham, at 165-66, 277. The atrocities, suffering, and resistance in Amdo were even less known in Lhasa or the outside world than those in Kham.

1957—Mao Temporarily Retreats

On February 27, 1957, Mao gave a speech promising to postpone "Democrat reforms" in Tibet until they were supported by "the great majority of the people." Mao Zedong, On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People, Speech at the Eleventh Session (Enlarged) of the Supreme State Conference (with additions by Mao before publication in People's Daily, June 19, 1957). "Democratic reform"was the Chinese communist euphemism for totalitarian rule, elimination of religion and of civil society, confiscation of all property, and forced labor.

Mao did not like having to say that he would halt "democratic reform" in Tibet. But the words in his speech had been forced on him by other party leaders, including CCP Vice-Chairman Liu Shaoqi, who were not as blase as Mao was about the Tibet Uprising. Liu's actions contributed to his later being purged and tortured in Mao's Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966.

Mao's February 1957 speech was soon shown to be a lie. The regime announced that all Tibetan arms would be confiscated. As the Dalai Lama later recalled, when he heard about the confiscation order, "I knew without being told that a Khamba would never surrender his rifle—he would use it first." Roger Hicks & Ngakpa Chogyam, Great Ocean 102 (1984) (authorized biography). According to secret PLA documents, the PLA worried there were about 100,000 to 150,000 rifles owned by the Tibetan army and people. Ben Kieler, The 1959 Tibetan Uprising Documents: The Chinese Army Documents 32 (2017).

As Gompo Tashi explained:

No Tibetans, and especially the fiercely independent tribes, would voluntarily surrender their weapons to the Chinese. If there was a single act by the Chinese that galvanized the resistance it was probably this plan to seize all weapons from the Tibetans. It could be interpreted by a Tibetan to mean but one thing: total loss of freedom. It was, in effect, the final insult. There would be no more broken promises.

McCarthy at 129-30. "For hundreds of years our weapons had been more precious than jewels. And now the Red Devils expected us to simply let them take our weapons away from us? We had no choice but to move forward with our plans to fight." Id. at 132.

In June 1957, the CCP further reneged on Mao's February promise. The communist "democratic reform" would be imposed within Central Tibet, in a Khampa area known as Chamdo. Meanwhile Khampa, Amdo, and Golok cavalrymen continued to raid PLA conveys and capture their arms.

The Dalai Lama

Gompo Tashi kept on working to raise and unite national resistance forces. To provide cover for the necessary nationwide travel and meetings, a plan was created to present the Dalai Lama with a bejeweled golden throne. Gathering the materials for the gift required much networking among potential donors all over Tibet; the kind of people who could donate gold or jewels for the throne were also likely to have plenty of arms and money to contribute to the resistance. The magnificent throne was presented in a ceremony on July 4, 1957.

While the Chinese saw the throne as just another example of Tibetan superstition, it was also a political statement understood by Tibetans. The throne was a gift from all three provinces of Tibet (Kham, Amdo, and U-Tsang), united in loyalty to the Dalai Lama and not to Mao Zedong.

Gompo Tashi met with the Dalai Lama, who viewed the planned national resistance army as inspired fighters with a just cause but no hope of success. The Dalai Lama advised Gompo Tashi that if he did choose to lead an army, he must do so with compassion and in full awareness of the consequences; the path might not be easy, but it might be the only one. The rebel leaders then consulted the oracle of Shukden, who told them no longer to remain idle; it was time to Tibetans to rise as one.

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

Created in 1947, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency was open to, but cautious in, aiding anti-communist rebels. Earlier in the 1950s, the Agency had been duped into attempted support for planned anti-communist uprisings in Poland and Albania, only to eventually discover that they were actually sting operations run by the communist secret police. In the early 1950s in China, the CIA's airdrops for anti-Mao revolutionaries had come to naught. Although communism in China was increasingly unpopular, many Chinese did not view rebels aligned with Taiwan's Chiang Kai-Shek as a credible alternative. Even many non-communists considered Chiang's rule of China to have been a failure.

Getting information on conditions in Tibet was very difficult. When the people of Hungary revolted against communist dictatorship in October-November 1956, the news was disseminated worldwide immediately. But the 1956 uprisings in Eastern Tibet were almost unknown to the outside world.

By the summer of 1956, the CIA had determined that reports of the Eastern Tibetan uprisings with impressive initial successes were genuine, and not mere Chiang Kai-Shek-style bluster.

Since the early 1950s, the CIA had been in touch with the Dalai Lama's elder brother, Gyalo Thondup, who quietly became the rebels' principal ambassador and contact with the world. In the CIA's new program to aid the Tibetans, the Dalai Lama's brother was the principal leader, and Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang the head of operations.

In 1957, several Tibetan freedom fighters were exfiltrated and then taken to Saipan for a pilot program of training in guerilla warfare. (The Pacific island of Saipan is part of the U.S. territory of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; it was previously a U.N. Trust Territory administered by the United States.) The program was soon expanded, with a permanent training center established at Camp Hale, Colorado.

The Tibetans and their American trainers got along very well. One instructor remembered, "They really enjoyed blowing things up during demolition class, but when they caught a fly in the mess hall, they would hold it in their cupped palms and let it loose outside." Kenneth Conboy & James Morrison, The CIA's Secret War in Tibet 107 (2002).

Besides training, the United States also began airdrops of supplies to the resistance fighters, eventually making about three dozen airdrops through 1965. An airdrop in the fall of 1958 included Lee Enfield .303 bolt action rifles, 60mm mortars, 2.36 inch bazookas, 57mm recoilless rifles, .30 caliber light machine guns, and grenades. (All the measurements are muzzle diameters.)

The equipment had been chosen for plausible deniability; it was the type of material that had been used in Asia in preceding decades by many different forces. By 1959, the CIA grew less considered about deniability, and began supplying the M-1 Garand, the outstanding American semi-automatic rifle from World War II. But the quantity of arms and ammunition was not sufficient to supply all of the freedom fighters.

Unfortunately, by the time the assistance program was up to speed, it was too late to make a great difference. If it had begun earlier in the 1950s, its effect could have been dramatic. Aid could have come sooner if the Dalai Lama had renounced the 1951 Seventeen Point Agreement (which he finally did in March 1959) and had requested aid. He was, after all, head of state, and his blessing would have made the Americans more confident about intervening earlier, including by having a firmer basis in international law.

The aid program was also hindered by lack of express support from the government of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who, at least in public, was playing a game of supporting China's claims to Tibet.

Nehru hoped that he was joining Mao in some sort of Asian anti-imperialist bloc. But what he got was the elimination of Tibet as a buffer between India and imperialist communist China. Using Tibet as a base, China in October 1962 would invade and seize 43,000 square kilometers of territory from northern India.

The post Tibet's armed resistance to Chinese invasion appeared first on Reason.com.