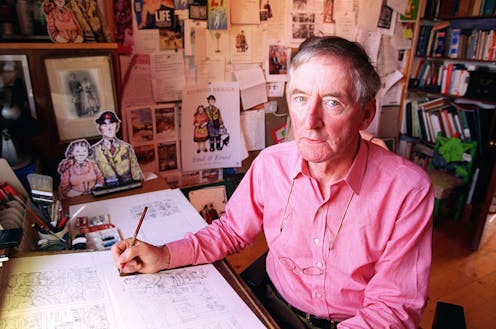

Raymond Briggs, who died on August 9 aged 88, transformed the way we see and value the strip cartoon and graphic novel in this country. Briggs’ great achievement was to make the form intellectually respectable through telling stories about seemingly ordinary characters, which were rendered skilfully in the egalitarian medium of coloured pencil.

Born in suburban London in 1934, Briggs had an early ambition to become a cartoonist but this was met with disappointment from his parents, who didn’t see it as a respectable or financially secure choice. After experiencing more snobbery from his teachers at both Wimbledon and Slade art schools, Briggs began his career as a professional illustrator working on conventional children’s books.

The default at the time was to treat words and pictures as separate entities. It wasn’t until the 1960s that he explored his talent and skill to combine both words and pictures, utilising the form of the strip cartoon that defined his future work.

Briggs is best known for his wordless masterpiece The Snowman, published in 1978, essentially a sweet children’s tale. But the loss of his parents Ethel Bowyer and Ernest Briggs in 1971, and his wife Jean Taprell Clark in 1973, imbued an unsentimental directness in his work.

As we mark his passing, it seems fitting that we look at back at three books that each say something quite sweet and poignant about the human condition and elevated the form of graphic novels.

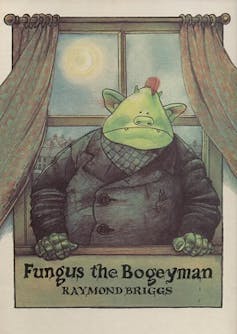

1. Fungus the Bogeyman (1977)

The success of the curmudgeonly Father Christmas and its sequel Father Christmas Goes on Holiday in 1975 established a loyal readership that enabled Briggs time and space to explore more experimental territory, like the wonderfully melancholic nihilism of the children’s book Fungus the Bogeyman published in 1977.

It follows a day (night) in the life of Fungus, a working class bogeyman whose job is to scare humans, as he begins to question the point of his work.

In Fungus, we see Briggs capture the mood of 1970s England through a slimy fairytale. The lights are out. The familiar domestic settings Briggs employs in many of his books is there from the start. Fungus’s wife Mildew rousing her husband in the marital bed: “Time to get up, Fungus my dreary. It’s nearly dark.”

The world-weary introspective musings of Fungus play to young and old readers alike. I recommend reading in slow voice to really get a sense of the wonderful sluggish and downtrodden nature of Fungus: “Oh well, here we go … Off to work again … Onwards always onwards, In Silence and in Gloom.”

It pre-empts both the wave of strikes that would result in Britain’s “winter of discontent” of 1978-79 and the “upside-down” world of the Netflix science fiction series Stranger Things. Briggs flips us, far underground, to the slow, damp, slime of Bogeydom. The world is drawn is exquisite detail employing a cold colour palette of grey greens, muted blues and browns that create its alluring bleakness.

Briggs playfully subverts the graphic convention of the comic strip, drawing in blacked out panels that have apparently been censored by the publisher in the interests of decorum. One such panel declares: “The Publishers wish to state that this picture has been deleted in the interests of good taste and public decency.”

Diagrams, footnotes and an array of asides are “pinned” throughout the story, adding detail and depth to the culture of Bogeydom. One aside, for example, reads: “Bogey umbrellas are upside down. They are designed to catch water and shower it onto the user.” The story is carefully structured, richly detailed and beautifully drawn, unsurprisingly taking Briggs two years to complete.

2. When the Wind Blows (1982)

Briggs resurfaced in 1982 with the politically charged, cold war graphic novel When the Wind Blows, further developing the characters of Jim and Hilda Bloggs from his 1980 book Gentleman Jim.

Briggs was inspired by the absurd and outdated Protect and Survive public information pamphlet, which had been published by the British government in 1980 to advise the public what to do in the event of a nuclear attack. He used the advice within the book to show how shockingly inadequate it was.

The story sets the horror of a nuclear apocalypse against the domestic backdrop of Jim and Hilda’s retired life in rural England. The warmth and geniality of the old couple’s interactions are punctuated by ominous double page spreads of the impending attacks.

Scale is used to brilliant effect, contrasting the tightly ordered panels framing the couple’s organised home life against spreads of military hardware that break the boundary of the page. The inevitable nuclear explosion obliterates the structure of successive pages, and their lives.

It is graphically stunning, with the following frames bent all out of shape until they return to a stable rectangle punctuated with a Briggsian “Blimey!”. The remainder of the book is bleak and achingly sad, a testament to Briggs’ skill with his pencils, empathetic dialogue and willingness to face finitude head on.

3. Ethel and Ernest (1998)

In the 1990s Briggs turned his attention to his own parents in his graphic memoir Ethel and Ernest. It unflinchingly tells the story of how his working-class parents met, and then raised their only child, Raymond.

Their lives are played out against the social and political upheavals taking place through the middle of the 20th century, including the depression, second world war, the birth of the welfare state, television and the Moon landings.

It is both deeply personal yet typically universal, a loving and unsentimental social history document. The British class system is played out through Ethel’s respectable conservatism and Ernest’s ideological socialism.

Though politically polarised, they are kind and stoic, wanting the best for their son. They died in 1971 within months of each other, their son rendering their end with characteristic directness. How proud and amazed they would undoubtedly have been to see what he achieved. Blimey!

The contemporary American cartoonist Chris Ware, much admired by Briggs, said of comics, “There is a magic when you read an image that you know doesn’t move but you have a sense that something is moving, if not on the page, then in your mind.”

While there are many much loved film and television adaptations of Briggs’ work, it is sitting quietly and patiently with his books where that humane magic can be found.

Matthew Edgar does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.