The Burgess Shale is located in British Columbia and is a site of marine fossils that are 506 million years old. It is celebrated for its “weird wonders,” containing a treasure trove of astonishingly well-preserved fossils.

These organisms harken back to the Cambrian explosion, a time in Earth’s history when major animal groups were diverging from each other in a burst of evolutionary innovation. In addition to the first representatives of most surviving animal groups, Cambrian deposits preserve a menagerie of sea-dwelling invertebrates unlike anything alive today.

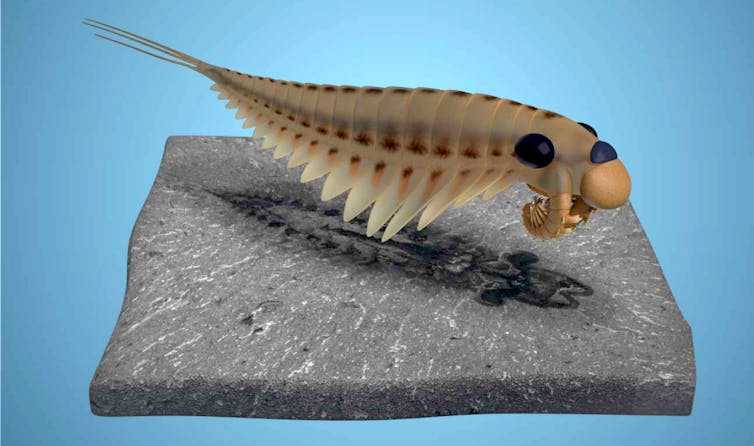

One of these bizarre animals is Stanleycaris hirpex, a distant arthropod cousin of insects and spiders. As a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto, I had the privilege of working with a previously unstudied collection of Stanleycaris fossils from the Burgess Shale. Before this, Stanleycaris was only known from fragmentary bits and pieces. Our study is the first to reveal intact specimens. The amazing preserved details give us insight into the evolution of the brain and head in the most diverse group of animals.

Famous fossils

Stanleycaris is a relative of one of the most iconic animals of the Cambrian, Anomalocaris. Both were predators with bulging compound eyes, round, tooth-lined jaws, swimming flaps and a pair of jointed frontal claws used to snare prey. These and other species were members of a diverse group called radiodonts, which were among the first to branch off from the arthropod group. This happened prior to the evolutionary divergence of major living subgroups like insects, arachnids and millipedes.

Smaller than the size of a human hand, Stanleycaris is shorter than the metre-long Anomalocaris, but no less odd-looking. The new fossils are also much better preserved, showing surprising features.

For example, Stanleycaris sports a large third eye in the middle of its head, between the two compound eyes. This has never been seen before in a radiodont, and emphasizes that these early arthropods had already evolved a complex array of different visual organs to help them navigate the ocean depths. This can also be seen in many of their distant modern kin.

However, perhaps the most exciting discovery is the preservation of much of the central nervous system of Stanleycaris in stunning detail. The fossils show that the brain of Stanleycaris surrounds part of the digestive tract. The brain is likely composed of two segments connected with the eyes and the frontal claws, respectively. Behind the brain are a pair of filamentous nerve cords that run along the belly of the organism.

A head-scratcher

For decades, an academic dispute raged over the “arthropod head problem.” This debate has far-reaching implications: The bodies of arthropods are made up of a repeated series of segments, and understanding how head segments line up is key to unlocking an understanding of nearly every aspect of their anatomy and evolution.

Since arthropods make up roughly 85 per cent of living animal species, this is important for understanding the origin of much biodiversity.

Much progress has been made on the problem, particularly for living arthropods, in which recognition of a ubiquitous brain composed of three segments — a protocerebrum, deutocerebrum and tritocerebrum — was critical.

Fossils have proven more difficult to interpret, as only limited information is preserved. Information on brain anatomy is extremely rare in the fossil record.

However, over the last decade this has begun to change with the discovery that some Cambrian deposits can occasionally preserve remains of nervous systems. Although so-called neuropaleontology is not without controversy, these discoveries have shed some light on the evolution of arthropod heads in early fossil groups.

Turning arthropod heads

Owing to their early divergence in the arthropod group, radiodonts are well-positioned to help inform the ancestral traits of arthropods. However, the alignment of their head segments with other extinct and living groups has been unresolved.

Prior to our study, the only information on brain anatomy came from a single specimen from China showing only partial preservation, the interpretation of which was contested. Based on new Stanleycaris fossils, we can now say with confidence that the radiodont brain already included both the protocerebrum and deutocerebrum. The protocerebrum was connected with the eyes of Stanleycaris, while the deutocerebrum innervated the large frontal claws.

Other fossil groups — such as certain worm-like animals called lobopodians, taco-shaped arthropods called isoxyids, and megacheirans, which look similar to radiodonts but have jointed limbs instead of flaps — share similar-looking frontal appendages.

Based on our discoveries in Stanleycaris, we think all of these structures share a common origin. Ultimately, these grasping frontal appendages were transformed into the sensory antennae of insects, the fangs of spiders, and their equivalents in other living groups.

While our new research is by no means the end of discussion about the arthropod head, it represents a key leap forward in understanding the evolution of this diverse and significant group of animals.

Joseph Moysiuk receives funding from a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Vanier Scholarship.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.