Mark Knopfler is one of the most successful British musicians in history, and one of the most admired guitarists. With his former band Dire Straits, he sold more than 100 million albums worldwide, and he’s worked with everyone from Chet Atkins to Bob Dylan. In 2019, as he prepared to release his ninth solo album, Down The Road Wherever, he sat down with Classic Rock in West London to look back on a career like no other.

Several years ago, Mark Knopfler was riding his motorbike not far from his home in central London when he was sideswiped by a car. The impact sent him spinning, smashing his bike and breaking his collarbone and seven ribs. His injuries could have been worse, but they were still serious enough to make a man whose entire career has been built on playing the guitar worry if he would ever be able to pick up the instrument again.

“I had what they called frozen shoulder,” Knopfler says today. He mimes stiffly attempting to hold a guitar. “I couldn’t get a Fender in. Apparently if you’ve got a broken collarbone your body stops it working. I asked the doctor how long it would last. He said: ‘I don’t know. Could be a short time, might not come back at all. Good luck.’” He chuckles, which he does often. “That was quite scary.”

The fact that Knopfler has just released his ninth solo album, and he’s currently sitting here in a discreetly classy West London restaurant talking about it, is a large spoiler as to what happened next. The ensuing course of physical therapy worked, his shoulder unfroze and he picked up where he left off with both his guitar and his bike.

But the drama of the crash isn’t really the point here. It’s the fact that Mark Knopfler – who as the former leader of Dire Straits and subsequently a successful solo artist has sold upwards of 100 million records and was recently estimated by the Sunday Times Rich List to have amassed a fortune of £75 million – was pootling around central London on a motorbike when he could have called up a gleaming chauffeured limo to transport him in considerably more style and with considerably less peril.

“Why would I do that?” he says, looking genuinely baffled. “Two wheels. There’s no other way to get around London. Except the Tube. When I played the O2 [in 2015], I got the Tube from South Kensington. Said hello to a lot of people. They were very nice.”

Traveling on the Tube to his own arena gig seems like a very Mark Knopfler thing to do. The Glasgow-born, Newcastle-raised 69-year-old is the least starry megastar you’ll ever meet. And ‘megastar’ isn’t overstating the case, not if you’re going by numbers alone. Dire Straits were the biggest-selling British band of the 1980s. Their fifth album, 1986’s Brothers In Arms, fired the starting pistol on the CD era and went on to sell more than 30 million copies.

Knopfler himself has long been a go-to collaborator for music’s A-listers – Bob Dylan, Rod Stewart and old mate Sting, and younger bucks The Killers and The Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach have called on him to lend his inimitable guitar playing and, less frequently, laconic vocals to their albums.

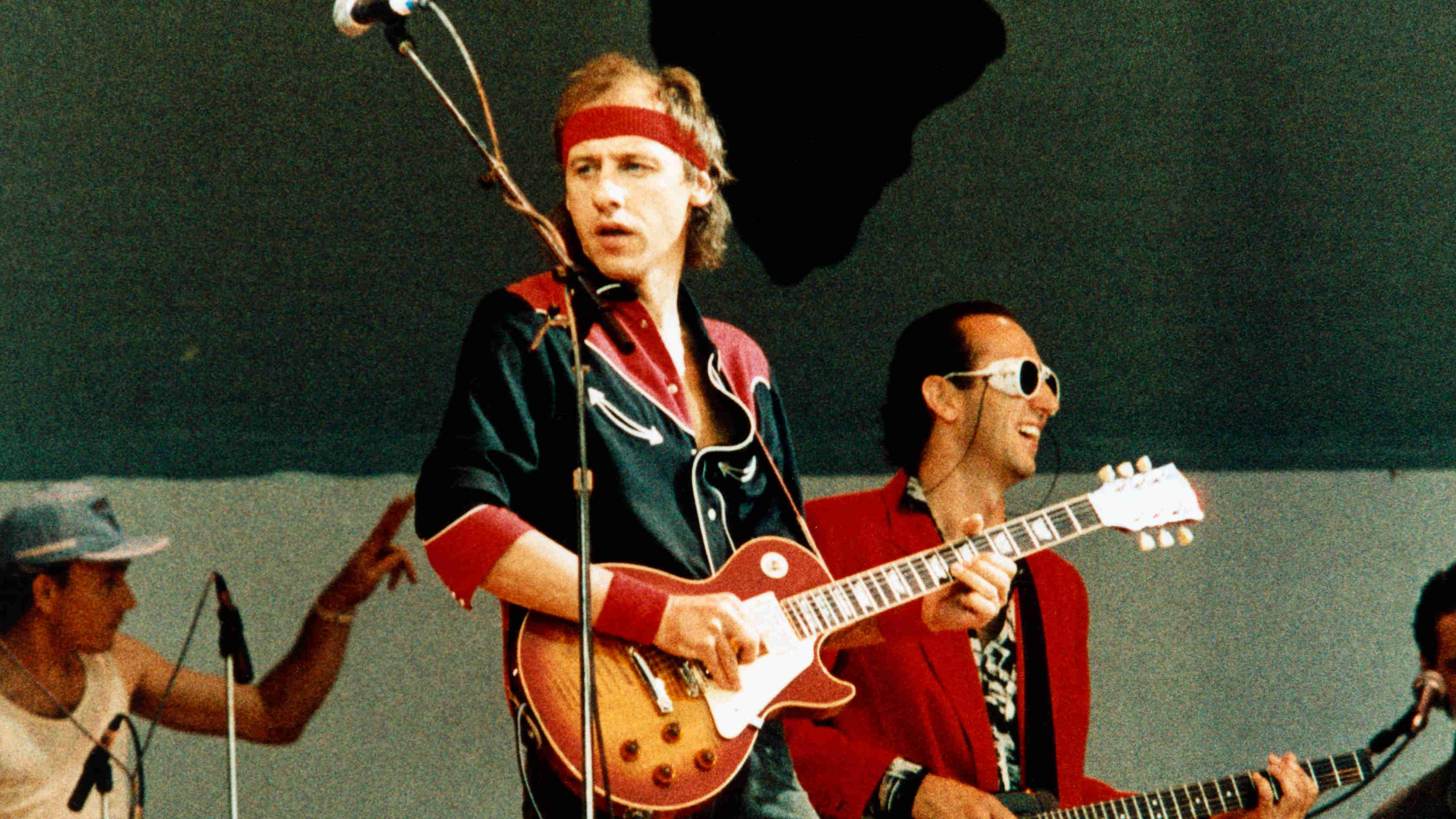

Knopfler is here today to talk about his own album, Down The Road Wherever. He arrived alone, a few minutes early, having walked from his manager’s office, wearing a thick jacket and woolly beanie hat that serve more to keep out the cold than render him unrecognisable as one of the most successful musicians Britain has ever produced. Even without the beanie you have to squint to see the scrawny guitar slinger he once was (the toweling headbands were retired years ago, the last wisps of hair shaved to the skull more recently).

He’s warm and friendly, but sometimes drifts off into vagueness. It’s not entirely clear whether that’s what he’s like or if it’s a polite way of avoiding talking about subjects he doesn’t really want to go deep into. Like Dire Straits.

Much like the man who made it, Down The Road Wherever is modest and assured at the same time. It glides between the windswept Celtic rock of Tracker Man and Drovers Road to the Mersey Delta blues of Just A Boy Away From Home (Knopfler is a lifelong Newcastle United fan, but the latter references Liverpool’s terrace anthem You’ll Never Walk Alone). The album’s title comes from a line in his song One Song At A Time, itself inspired by something Knopfler’s great hero Chet Atkins used to say.

“Chet and I got to be got to be good friends,” says Knopfler. “I think he took pity on me because I was a picker. Anyway, one day he was telling me about his childhood, which was very tough; not having a coat to go school in, having to walk to school, his family were very poor. And he said he picked his way out of poverty one song at a time. It just stuck in my mind.”

The phrase resonated with Knopfler. He may not have grown up in abject poverty, but there was little spare money around when he was young. “Everything went on the house and feeding the family,” he says. “There wasn’t much left afterwards. It took a while to convince my dad to part with fifty quid for this electric guitar I wanted. And once I got it I realised I needed to buy an amplifier. I couldn’t ask him for an amp as well, so I wired up an old Marconi radio – and blew it up in short order. And then I used to torture my poor mum and dad. After they go to bed at night I’d be downstairs thumping away in this little house.

Were your parents supportive?

“Yeah, really they were. When you consider the fact that popular music was looked down upon by respectable society. There were no guitar lessons in school. It was frowned upon: ‘Knopfler, I might have known you’d be involved in this [disparaging voice] rock and roll, boy.’”

Knopfler may have been an early adopter when it came to rock’n’roll, but it would be a long time before rock’n’roll paid the bills. Pre-Dire Straits, he worked as a local newspaper journalist (one early job was writing a Jimi Hendrix obituary), taught English at a college in Essex, got married, passed through a handful of pub-rock bands and shuttled between the North and the South.

He was 28 when he formed Dire Straits with his younger brother David and bassist John Illsley. The latter pair shared a rundown flat in Deptford, South London, which became the band’s HQ.

“Oh, Deptford really was an armpit back then,” says Knopfler. “The flat that John and David shared and I started living in once I came down to London was condemned. The only reason they didn’t pull it down was that they were so well-built. There’s a plaque on the door there now. It’s amazing nobody’s stolen it.”

Dire Straits arrived at a time of flux. Pub rock had been superseded by punk, at least in the capital. But the cultural shift wasn’t quite as brutal or overwhelming as history has it. The band swiftly carved out a place for themselves on the late-night circuit. Was it a romantic time?

“No, it wasn’t particularly, but it was a thrill to be part of all that,” he says. “It was completely absorbing for me. It was the first time I got a thing with four wheels on it that I could actually put my songs on to. That’s all I was looking for.”

Dire Straits’ first single, in 1978, was Sultans Of Swing, a taut slice of South London choogle that told the tale of a semi-fictional jazz band stubbornly papering over their hopeless prospects. The song’s vivid but sympathetic narrative showed that this one-time English lecturer was among the most underrated lyricists of the era.

Unlike the band in the song, Dire Straits’ prospects were bright. Within six months the song had made the Top 10 on both sides of the Atlantic. For the 28-year-old Knopfler, the fact that success had taken so long coming was a blessing in disguise.

“When you’re eighteen you think you’re the centre of the universe. And unfortunately you go round behaving like you are.”

Were you guilty of that?

“I don’t believe so, because at twenty-eight it’s very different. And I don’t think I’d have been allowed to. You can’t come from where I come from and get away with that. It tickles me sometimes, reading what people do when they’re young because it’s part of that rock’n’roll dream – being successful, being too young to cope with it. Sometimes I look into the faces of kids who are nineteen or twenty-two or something, and I’ll try and see them twenty-five years ahead, try to imagine what’s going to happen them. [Sighs] But then you can’t really know what will happen. Being the age I was, that means everything. If I’d been eighteen I’d have been dead.”

Really?

“How many people do you know who have been worshipped and deified as children who are undamaged? Do you know any? It’s a very small list, your honour. I’d already done loads and loads of jobs by that point. If you haven’t unloaded a lorry, you can never quite come to grips with reality. You have to know what work is like. And know what’s in people’s heads.”

Did you know you were going to be successful when you started Dire Straits?

“No, not really. Occasionally you might get one or two people saying: ‘Hey, man, you’ve really got it.’ But you can’t let all that stuff go to your head. The other thing is, if you’re in the eye of the storm you’re cushioned inside it.”

Received wisdom is that Knopfler seized control of Dire Straits around the time of their third album, Making Movies. It certainly caused tension between him and his brother David, who quit during sessions for the album.

“Always had it,” Knopfler says today, meaning control of the band. “If you write the songs, sing them, play them, then you have it. I absolutely revelled in it. I still do. I feel so comfortable. It’s like being in charge of a little fighting ship. It suits me down to the ground.”

Calling Dire Straits “a little fighting ship” is like calling Brexit “a little bit of a distraction”. Between their debut album in 1978 and Brothers in Arms eight years later they went from the back rooms of London’s pubs to the arenas and stadiums of the world. Knopfler and John Illsley were the sole constant members throughout that time.

But somewhere along the way, success turned Dire Straits turned into a chore. Knopfler disbanded the group temporarily in 1987, following an exhausting tour in support of Brothers In Arms. He reunited them for 1991’s little-loved On Every Street, then disbanding them permanently a year later.

“I was burnt out. Shredded,” he recalls. “I remember being in Amsterdam, lying on my bed, feeling like somebody had pulled all the wool out of me. You become conscious of a reversal. You’re a songwriter, you’ve been looking at the world, and suddenly all the world’s looking at me now. It’s actually a false impression, because the world doesn’t give much of a crap about you. I learned pretty quickly that a majority of people don’t really care about the music that much.”

Since disbanding Dire Straits he has pursued a career that has seen him alternate between solo recordings and appearances on an entertainingly random array of other people’s records, of whom John Fogerty, Weird Al Yankovic and US art-rockers the Dandy Warhols are just a few.

But the one thing he continues to show zero interest in is reassembling the band with which he made his name. When Dire Straits were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 2018, he was noticeable by his absence. Asked why he wasn’t there, his answer is politely but vague.

“My manager Paul Crockford and I, we see eye to eye on a lot of things. Somebody called him up and arrogantly told him what was going to happen, what day it was, who would be playing, and afterwards how we’d go and talk to the press…’ You can’t talk to somebody like Paul like that. You can’t talk to someone like me like that [trails off]. It’s a very nice recognition, I’m sure. It’s bigger in America. It’s not very British, is it?”

You seem to have an ambivalent view of Dire Straits these days. Are you proud of what you did?

“Of course I am. I’m proud of those songs. I wrote them and I’ll still play them. They’re signposts for people’s lives. If I play Brothers In Arms, you better believe it means so much to people. People have used Coming Home, from Local Hero, for births, marriages, the whole thing. A bloke told me the other day his indulgence is being in the car on his own so he can listen to Telegraph Road twice.

“These songs walked away from me long ago. They belong to you now. I feel very privileged to be able to play them for people. But at the same time you’ve got to try and protect yourself from being a cabaret thing.”

There’s a song on Down The Road Wherever titled Good On You Son. On it, Knopfler sings about an ex-pat Brit who has swapped the ‘grimy sink estate’ where he grew up for the lemon trees, freshly ground coffee, business meetings and ‘sun and shameless blue’ of Los Angeles.

In anyone else’s hands it would come over as a sneery and loaded with a kind of inverse snobbery. But that’s not Knopfler’s style. Instead the over-riding emotions are admiration and respect.

“It’s a composite in my mind of anybody who has made something for themselves,” he says. “People wrinkle their noses in disgust when they hear that John Lydon is doing a butter ad. I just think: ‘Good on you, son.’”

Why?

“Because he’s pulled himself out of shit [laughs]. One ad at a time. It’s so easy for people to judge.”

But you’ve written about the people who haven’t made it, too, like the band in Sultans Of Swing.

“It’s a big thing.”

Who do you identify with most, the success stories or the failures?

“Well I’m very much a glass-full personality. I admire grit. Having the desire to stick with something. I remember when I walked out of the shop with my first guitar, the old guy said: ‘Stick at it.’ So I did. And it was hard. I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to play, but it’s difficult. Cos your fingers don’t want to go to those places. The body doesn’t always answer what you ask it.”

Do you enjoy being famous?

“I would recommend success to anybody. It’s wonderful. If I show you my studio [British Grove, in East London] you’ll understand what I’m talking about. The studio is an illogic these days. But I don’t want a jet or a boat. Fame is something different. That’s a by-product of success. Fame’s the exhaust – all the crap that comes out of it. If you can think of something good about fame, I’d like to know.”

Knopfler isn’t sure how long he can keep doing this. He’s not talking about anything so dramatic about retirement – as well as Down The Road Wherever, he’s also working on songs for a musical version of the 1984 film Local Hero, for which he composed the music. It’s more about scaling things back in terms of road work.

“You do three things – write, record and tour,” he says. “And you get to an age where touring becomes the first casualty. I used to play six nights a week. Now I’m down to probably three. I love it. But I’ll have to stop some time.”

What will you do with the down time?

“I still have rather foolish ambitions to undergo a course of study.”

Of what?

“The guitar. Not a structured music lesson, just somebody that comes round and rings the bell and gives me a little thing to think about.” He looks wistful for an instant. “Probably a jazz-based player. I actually hold it like I’m fixing a truck tyre. I play like a plumber.”

It sounds faintly ridiculous to hear one of this country’s most successful, and acclaimed, guitar players talking like this. But then this is Mark Knopfler, and flash and ego is someone else’s job. Earlier he talked about one of the proudest moments of his life. It wasn’t receiving his umpteenth platinum disc for Brothers In Arms, or being Bob Dylan appointing him as his musical director, or being in a position to ignore the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame.

“It was after a gig. I don’t remember where it was or where I was going, but this bloke just stopped me in a corridor. He said: ‘I want you to know that I was suicidal before I came out tonight. It took my friends to drag me out. But after seeing you, I just want you know to know I’m going on.’ He smiles again. “That was wonderful. I’m a lucky, lucky man.”

Originally published in Classic Rock 261