THOMAS THE TANK ENGINE, 1984-present

The weird little world created by Wilbert Awdry – Anglican cleric, railway enthusiast and, one must presume, absolute banter legend – is an England that only exists in a dossier marked “ENDGAME” buried somewhere deep in the grumbling bowels of Ukip HQ. Here is a land where people can actually be called Percy without being thumped in the pancreas by everyone they encounter; a bucolic penitentiary of absolutely no women, of knowing your place, of respecting your betters, of following the pre-ordained, quite literal tracks laid before you. You can go as where you please, as long as it’s exactly where you’re told. Do not deviate. Freedom here is an illusion. Example: Percy – a total arse, by the way – gets a new coat of paint. He boasts it makes him waterproof. Thomas and Henry tell him to stop faffing around and just do as he’s told. Percy ends up stranded a pond, contrite, lesson learned. This, with infinitesimal variations, is the whole show, every week. The blatancy of the behavioural conditioning is astonishing – its bimbly-bombly theme tune is basically a Pavlovian trigger for thoughtless subservience. Ringo Starr’s narration would feel like class betrayal were it not for the fact he clearly has no idea where he is or what’s going on. Toe the line, he says, and listen to The Fat Controller because He knows best. A balder metaphor for kowtowing to the whims of The City you will never see. Luke Holland

TELETUBBIES, 1997-2001

An early controversy attached to the Teletubbies – four infant aliens who lived among the eye-wateringly verdant hills of Teletubbyland at the turn of the millennium – was that nominally male character Tinky Winky sometimes carried a handbag. Nowadays that just looks like a healthy and progressive disregard for gender norms. What is unsettling, however, is the role of technology in the Teletubbies’ leisure-based post-capitalist existence. Metal speakers sprout from the foliage to boom out instructions, as each episode sees the protagonists summoned to a sparking windmill, where one of the screens embedded in their stomachs plays a video.

Often the films (which enrapture the Teletubbies) feature a group of children enjoying prelapsarian life: blowing bubbles, pointing at birds, generally unburdened by tech’s siren call. But these videos may as well be ancient historical records as far as the Teletubbies are concerned, who aren’t so much sentient beings as vessels for the transmission of aimless content, and who don’t so much experience the world as live vicariously through the version streaming out of their tummies. As man and machine meld to nightmarish ends, the Teletubbies issue a grim warning. It’s a shame nobody heeded it. Rachel Aroesti

CLANGERS, 1969-1974

The Clangers invited its young audience to contemplate man’s forthcoming active role in the wider universe. Oliver Postgate, its creator, fully expected his infant audience – tomorrow’s space generation – to absorb lines such as “this calm serene orb, sailing majestically among the myriad stars of the firmament,” voiced over a tracking shot of the cosmos, an intertextual allusion to the Powell/Pressburger film A Matter Of Life And Death. Sadly, in this the post-space age, Clangers has proven hauntological rather than prescient.

Although impressive in its construction of an entire fictional language based on the long whistle, Clangers is not strictly cosmologically accurate. Planets are more than 100 yards in diameter and it is unlikely that any alien species would be knitted rather than procreated. The show is best considered as an eco-predecessor to The Wombles, with the armoured, resourceful Clangers forced to deal with the floating detritus of Earth (including television sets), the messiest planet in the galaxy. David Stubbs

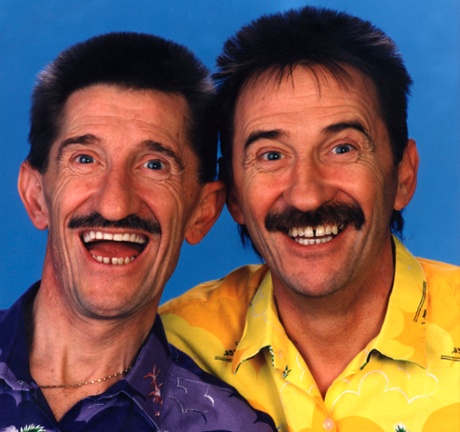

CHUCKLEVISION, 1987-2009

What slowly becomes clear in ChuckleVision – a 289-episode physical comedy about two brothers passing things to one another repeatedly – is that Paul and Barry Chuckle aren’t alive and corporeal like you and I, but are in fact dead, trapped in a slapstick purgatory of their own making, doomed to get a broomhandle shoved down the sleeves of their shellsuits, for ever. Because the big themes – Paul is smarter than Barry; Barry keeps dropping things; never walk quickly while carrying a cream cake – repeat ad infinitum, as do the main players: Dan the Van, their faceless employer; No Slacking, the same angry antagonist in different uniforms and hats; Mrs Blenkinsop, a woman. The Chuckles never age, never remember old adventures, never get harmed. The evidence is all there. Every episode of ChuckleVision is the just dying flickers of Barry’s brain as he slips out of a ladder fall coma and peacefully into death. There never was a Dan the Van. Paul wasn’t real. When death awaits you, look it in the face and chuckle. Joel Golby

ZZZAP!, 1993-2001

These are dark times for print media. Every week you hear of another magazine or local newspaper closing because advertising revenue has dried up. The best minds in the industry have experimented with paywalls and micropayments, but no one seems to have come close to finding a solution, with one notable exception: the 90s CITV show ZZZap! Each week an 18ft giant Beano-style comic would come to life, in the form of filmed strips performed by entirely mute actors annotated with cartoonish actions like “Kapow!”, “A Bit Later…” or “Uh oh he’s farted”. The show ran for 10 series and some of the comic strips were syndicated for US network television – in other words an unmitigated commercial success. The editor of any print publication worth its salt should now be demanding to see tape of Cuthbert Lilly (catchphrase: “He’s dead silly”), a smalltown simpleton who’d get into ludicrous situations, or Daisy Dares You, a freckled prankster. They were the Owen Jones and Caitlin Moran of their day. Sam Wolfson

PLAYDAYS, 1988-1997

In his 1947 paper Superstition In The Pigeon, BF Skinner showed that birds, when given food at random intervals, would come to associate feeding with whatever action they were performing at the time, going on to repeat the action in the hope of further sustenance. Throughout the 1990s, the BBC staged a mass variation on the experiment called Playdays. Every weekday, the show’s iconic multi-coloured bus would come to a halt at one of five stops, the identity of which would dictate the content of the day’s episode. Schoolyard consensus favoured The Why Bird Stop, in which a talking bird investigated causality, though pre-teen factions also sprung up in support of the travel-themed Patch Stop, hosted by a sentient rag doll, and the musically inclined Roundabout Stop, wherein letters and numbers were celebrated with a vigour normally reserved for returning PoWs. Before long, children across the country were devising complex rituals aimed at telekinetically influencing the bus’s seemingly random daily port of call, which can only have come as a surprise to the show’s creators, who’d long ago allocated each stop to a different day of the week. Charlie Lyne

PINGU, 1986-2006

Watching Pingu as it child it always struck me as odd that my parents seemed to find the adventures of a claymation penguin as engrossing as I did. Only viewed at a distance of 25 years do I finally get it: Pingu is a children’s TV show entirely wasted on children. As if their tiny minds could appreciate the formal daring of the series: the unsettling starkness of Pingu’s Antarctic vista, pre-empting by a quarter of a century the froideur of Scandicrime drama; the frequent lapses into wild surrealism (witness the nightmarish Pingu’s Dream, where, in a scene that’s part Fantasia, part David Lynch, the tiny penguin imagines his bed can walk); and the muted, Loachian drama at the show’s core, as Pingu and his family try to get by in the forbidding frosty wastes. Regarding that last point, it’s worth noting that Pingu is as damning a depiction of parenthood as you’ll ever see: Pingu’s poor mother and father struggle to cope with his aberrant behaviour – the trashing of their igloo home, the bullying of his sister Pinga, his frequent attempts to run away – and it’s clear that his delinquent seal friend Robby comes from a broken home (we never see his parents). Not only, then, is Pingu not meant for children, it actively warns against having them, a bold and indeed necessary argument to make in our desperate age of overpopulation. Gwilym Mumford

EMU’S WORLD, 1982-1984

During the 1980s, Emu’s World was CITV’s golden goose, a long-running franchise that even spawned a Better Call Saul-style spinoff for its panto antagonist Grotbags. But viewed from three decades’ distance, the show – set in Rod Hull and Emu’s junk-filled Pink Windmill bachelor pad – seems confusingly archaic, even for its time. Why do Emu’s urchin pals keep doing classic Hollywood song-and-dance routines? And what’s up with Grotbags and her Jimmy Cagney impression (“You dirty brats!”)? It might seem as if the subtext is to upend the dominant gender colour-coding of the era, with the Pink Windmill consistently shown to be superior to the blue-walled Gloomy Fortress where Grotbags hatches her schemes to snatch Emu. But it’s really a stealthy prepper parable, demonstrating the self-sufficient benefits of having your own wind-powered energy supply and teaching repetitive lessons about how to fend off evil marauders who want to steal your livestock. There’s somebody at the door, kids! It’s an inescapable energy crisis and the subsequent breakdown of society. Graeme Virtue

BAGPUSS, 1974

Bagpuss seemed dusty and ancient even in the 70s. In 2015, taken at face value, it’s even more anachronistic; a Jeremy Corbyn in a world of Andy Burnhams. But things are never quite that simple – like Corbyn, it now serves as confirmation of the idea that if you stay in the same place for long enough, eventually everyone else will come full circle and join you. Its delightfully creaky folk trappings now feel strikingly prescient – it’s easy to imagine the Bagpuss soundtrack getting an exorbitantly expensive, limited edition re-release on 180 gram vinyl. And look, there’s a banjo-playing frog. It’s hipster cod-authenticity with a side order of Innocent smoothie-style wackaging.

However, what’s great about Bagpuss is that, ultimately, it’s the least “meta” TV show ever. It knows exactly what it is. Just as Corbyn is simply an elderly socialist who wants to renationalise British industry, Bagpuss is simply a programme about a funny, charming old shop where dolls come alive. Not particularly realistic, but what’s wrong with that? Phil Harrison

RAINBOW, 1972-1992

Ostensibly about three adorable best friends called Zippy, George and Bungle, Rainbow sees the trio being mentored by human man Geoffrey, a father figure who helps them navigate disputes over incredibly diverse topics such as who gets to build a tower of toy bricks and who gets to play with a wooden train. Why are a legless hippo, a massive bear and a zip-headed alien (he’s an alien, right?) sharing one bed in what is essentially a large cupboard, cared for by a weird old dude? It made little sense at the time, but the setup is clearly supposed to be a deeply dysfunctional family unit, with Bungle cast as the older brother, George as a stealth way to sneak a gay role model on to TV in the homophobic 80s, and Zippy as the attention-seeking naughty child. A closer look reveals Geoffrey’s parenting skills to be questionable at best: he zips up Zippy’s mouth to silence him, abandons his kids to go on a canal boat holiday and ignores the family for a day when the next-door neighbours get a puppy, leaving the “kids” so depressed that they go to bed during the day. Single parenting isn’t easy and Geoffrey’s too busy at work to give them the correct amount of care and attention they need. An upsetting foreshadowing of Broken Britain. Issy Sampson

THE MAGIC ROUNDABOUT, 1964-1971

As the antechamber to the nightmarish nightly news throughout the 1970s – Vietnam! Ulster! Provos! Stonehouse! Thorpe! Crisis, What Crisis?! – The Magic Roundabout offered a psychedelic pre-inoculation of the nation’s kids against the toxic effects of the headlines to follow. This French import, stripped of its original soundtrack and rewritten and revoiced entirely by Emma Thompson’s dad, Eric, became one of the accidental triumphs of homegrown English Surrealism, a candy-coloured universe that fairly screamed tangerine trees and marmalade skies, with sets made entirely of cellophane flowers (and such toothsome lines as “she said, acidly...”).

Thompson’s plummy, ineradicably English vocal overlay gave us Dylan, the stoner rabbit with his suspiciously joint-like carrot, Ermintrude the matronly singing cow, part Joyce Grenfell, part Hattie Jacques, Brian, the small and berkish snail, and the spring-loaded Zebedee, whose repeated “BOING!!!”s were filthy even to a five-year-old. For children it was enchanting, magical and strange; to their elders it was bizarre, acid-drenched and oddly dark. Forget the remakes, the revoicings and updates – the shoddy, worn-out original episodes still exert considerable genius and oddball charm. John Patterson

BERNARD’S WATCH, 1995-2005

The modern man requires more time. Time to forge a healthy work-life balance, to watch every Paul Rudd film on Netflix, to read each Corbyn-related article on the internet, to launch that raw food recipe blog. Perhaps what the modern man most requires, however, is Bernard’s Watch. Viewed almost two decades since its debut episode, in an age where time is as sacred as the Dead Sea Scrolls, the children’s drama about a boy who can stop the clock using a magical pocket watch plays out like a preemptive warning about society’s increasingly incessant schedules. Set on the sunny streets of British suburbia, Bernard must use his powers for nobelnoble, practical reasons, instead of petty theft, clocking off for a two hour nap or to repeatedly shout the word “ARSE” in his PE teacher’s face. Essentially, its underlying lesson is in how to use time to improve others’ lives, rather than to clutter our own. Well worth another watch. If you’ve got the time. Harriet Gibsone